Transcript: House Hearing on DHS and CISA Role in Securing AI

Gabby Miller / Dec 15, 2023

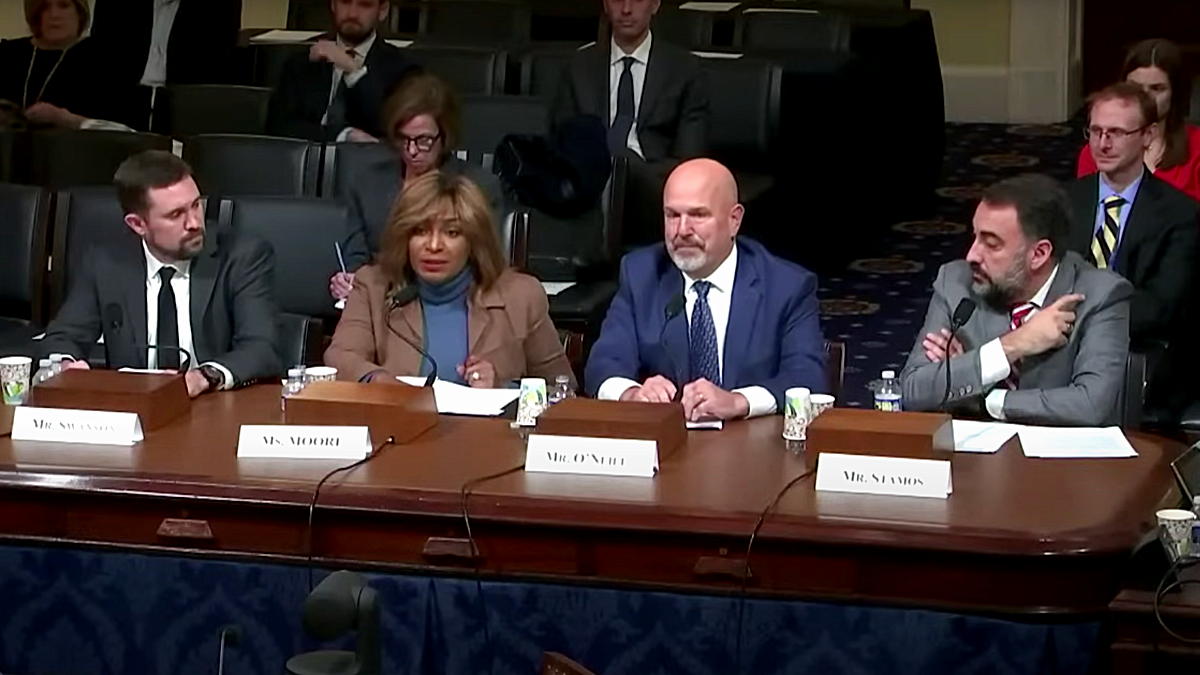

Witnesses at a House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection hearing entitled, “Considering DHS’ and CISA’s Role in Securing Artificial Intelligence,” December 12, 2023. Source

On Wednesday, December 12, the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection hosted a hearing titled, “Considering DHS’ and CISA’s Role in Securing Artificial Intelligence.” Chaired by Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY), and characterized as one of the “most productive” hearings of the year by Ranking Member Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA), the two hour session featured topics such as how to safely and securely implement AI into critical infrastructure, red teaming and threat modeling to defend against cybercriminals, and breaking out threat viability and attack mechanism infrastructure, among others.

Witnesses included:

- Ian Swanson, Chief Executive Officer and Founder, Protect AI

- Debbie Taylor Moore, Senior Partner and Vice President, Global Cybersecurity, IBM Consulting

- Timothy O’Neill, Vice President, Chief Information Security Officer and Product Security, Hitachi Vantara

- Alex Stamos, Chief Trust Officer, SentinelOne

Their written testimonies can be found here.

Much of the discussion around red teaming was led by witness Debbie Taylor Moore of IBM Consulting. In her opening remarks, Taylor Moore stressed the need for an AI usage inventory which would tell CISA where AI is enabled and in which applications, in order to help identify risks that could manifest into active threats as well as implement an effective AI governance system. One of the biggest challenges with red teaming AI systems will be remediation once the gaps are identified, according to Taylor Moore, reinforcing the need to upskill workforces across sectors. “I think that CISA is like everyone else. We're all looking for more expertise that looks like AI expertise in order to be able to change the traditional red team,” Taylor Moore noted. The goal is to have visibility into these systems, according to testimony Ian Swanson of Protect AI.

The conversation returned time and again to how standards and policies, as well as easy and swift access to different government agencies, will impact small to medium-sized businesses and localities facing cybersecurity threats. With newer and more widely-accessible AI capabilities, nefarious actors now have capabilities that only specialized workers at Lockheed Martin or the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service had four or five years ago, according to witness Alex Stamos of SentinelOne. “I think a key thing for CISA to focus on right now is to get the reporting infrastructure up. One of the problems we have as defenders is we don't talk to each other enough. The bad guys are actually working together. They hang out on these forums, they trade code, they trade exploits,” Stamos explained. One proposed way Congress could fill this gap is by sharing investigative resources from the Secret Service or FBI with local law enforcement.

Hitachi Vantara’s Timothy O’Neill emphasized the need for CISA to work across agencies to avoid duplication when developing requirements that AI systems must be tested for or comply with. Rep. Swalwell echoed this sentiment in his opening remarks. “Moving forward, harmonizing AI policies with our partners abroad and across the federal enterprise will be critical to promoting the secure development of AI without stifling innovation or unnecessarily slowing deployment,” he noted.

A small but significant portion of the hearing was also devoted to AI’s role in the 2024 elections. Rather than focusing on deepfakes of presidential candidates, Stamos believes that time would be better spent focusing on the ways AI is a force multiplier for content produced by bad actors. “If you look at what the Russians did in 2016, they had to fill a building in St. Petersburg with people who spoke English. You don't have to do that anymore,” he said. Now, a very small group of people will have the same capabilities as a large professional troll farm. The role of government in taking action against this type of mis- and disinformation is up in the air, with cases like Murthy v. Missouri (formerly Missouri v. Biden) pending in the courts over First Amendment concerns. “Instead of this being a five-year fight in the courts, I think Congress needs to act and say, these are the things that the government is not allowed to say, this is what the administration cannot do with social media companies. But if the FBI knows that this IP address is being used by the Iranians to create fake accounts, they can contact Facebook,” Stamos said.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the hearing.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

The Committee on Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection will come to order without objection. The chair may recess at any point. The purpose of this hearing is to receive testimony from a panel of expert witnesses on the cybersecurity use cases for artificial intelligence or AI, and the security of the technology itself. Following the administration's release of the executive order on safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence, I now recognize myself for an opening statement.

Thank you to our witnesses for being here to talk about a very important topic, securing artificial intelligence or AI. I'm proud that this subcommittee has completed thorough oversight of CISA's many missions this year from its federal cybersecurity mission to protecting critical infrastructure from threats. Now as we head into 2024, it is important that we take a closer look at the emerging threats and technologies that systems must continue to evolve with, including AI. AI is a hot topic today amongst members of Congress and Americans in every single one of our districts. AI is a broad umbrella term encompassing many different technologies use cases from a predictive maintenance alerts in operational technology to large language models like ChatGPT making, building a common understanding of the issue difficult as the general curiosity in and strategic application of AI across various sectors continues to develop, it is vitally important that the government and industry work together to build security into the very foundation of the technology regardless of the specific use.

The administration's executive order on EO is the first step in building that foundation. DHS and CISA are tasked in the EO with one, ensuring the security of the technology itself and two, developing cybersecurity use cases for AI. But the effectiveness of this EO will come down to its implementation. DHS and CISA must work with the recipients of the products they develop, like federal agencies and critical infrastructure owners and operators to ensure the end results meet their needs. This subcommittee intends to pursue productive oversight over these EO tasks. The timeline laid out in the EO is ambitious, and it is positive to see the CISA's timely release of their roadmap for AI and internationally supported guidelines for secure AI system development. At its core, AI is software and CISA should look to build AI considerations into its existing efforts rather than creating entirely new ones unique to AI.

Identifying all future use cases of AI is nearly impossible, and CISA should ensure that its initiatives are iterative, flexible, and continuous even after the deadlines in the EO pass. To ensure that the guidance it provides stands the test of time. Today we have four expert witnesses who will help shed light on the potential risks related to the use of AI and critical infrastructure, including how AI may enable malicious cyber actors, offensive attacks, but also how AI may enable defensive cyber tools for threat detection, prevention, and vulnerability assessments as we all learn more about improving the security and secure usage of AI from each of these experts. Today, I'd like to encourage the witnesses to share questions that they might not have yet the answer to. With rapidly evolving technology like AI, we should accept that there may be more questions than answers at this stage. The subcommittee would appreciate any perspectives you might have that could shape our oversight of DHS and CISA as they reach their EO deadlines next year. I look forward to our witness testimony and to developing productive questions for DHS and CISA together here today. I now recognize the ranking member, the gentleman from California, Mr. Swalwell, for his opening statement.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Thank you chairman, and as we close out the year, I want to thank the chairman for what I think has been a pretty productive year on the subcommittee as we've taken on a lot of the challenges in this realm. I also want to offer my condolences to the chairman of the overall committee for the families impacted by the devastating tornadoes that touched down in Chairman Green's District in Tennessee over the weekend. So my staff and I and the committee staff are keeping Chairman Green and his constituents and our thoughts as we grieve for those that we've lost as they rebuild. Turning to the topic of today's hearing, the potential of artificial intelligence has captivated scientists and mathematicians since the late 1950s. Public interest has grown, of course, from watching Watson beat Ken Jennings at Jeopardy to Alpha Go debating and defeating the World Champion Go Player in 2015 to the debut of ChatGPT.

Just over a year ago, the developments of AI over the past five years have been generating interest in investment and have served as a catalyst to drive public policy that'll ensure that the United States remains a global leader in innovation and that AI technology is deployed safely, securely, and responsibly. Over the past year alone, the Biden administration has issued a blueprint for AI rights, a national AI research resource roadmap, a national AI R&D strategic plan, and secured voluntary commitments by the nation's top AI companies to develop AI technology safely and securely. And of course, as the chairman referenced just over a month ago, the president signed a comprehensive executive order that brings the full resources of the federal government to bear to ensure the United States can fully harness the potential of AI while mitigating the full range of risks that it brings. I was pleased that this executive order directs close collaboration with our allies as we develop policies for the development and use of AI.

For its part, CISA is working with its international partners to harmonize guidance for the safe and secure development of AI. Two weeks ago, CISA and the UK's National Cybersecurity Center issued joint guidelines for secure AI system development. These guidelines were also signed by the FBI and the NSA as well as international cybersecurity organizations from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and Japan among others. Moving forward, harmonizing AI policies with our partners abroad and across the federal enterprise will be critical to promoting the secure development of AI without stifling innovation or unnecessarily slowing deployment. As we promote advancements in AI, we must remain cognizant that it is a potent dual use technology. Also, I just want to touch a little bit on Deepfakes, and I hope the witnesses will as well. They are easier and less expensive to produce, and the quality is better. Deepfakes can also make it easier for our adversaries to masquerade as public figures and either spread misinformation or undermine their credibility.

Deepfakes have the potential to move markets, change election outcomes, and affect personal relationships. We must prioritize investing in technologies that'll empower the public to identify. Deepfakes watermarking is a good start, but not the only solution. The novelty of AI's new capability has also raised questions about how to secure it. Fortunately, many existing security principles which have already been socialized apply to AI. To that end, I was pleased that CISA’s recently released AI roadmap didn't seek to reinvent the wheel where it wasn't necessary, and instead integrated AI into existing efforts like Secure by Design and software build of materials. In addition to promoting the secure development of AI, I'll be interested to learn from the witnesses how CISA can use artificial intelligence to better execute its broad mission set. CISA is using AI enabled endpoint detection tools to improve federal network security and the executive order from the president directs CISA to conduct a pilot program that would deploy AI tools to autonomously identify and remediate vulnerabilities on federal networks. AI also has the potential to improve CISA's ability to carry out other aspects of its mission, including analytic capacity.

As a final matter, as policymakers, we need to acknowledge that CISA will require the necessary resources and personnel to fully realize the potential of AI while mitigating the threat it poses to national security. I once again urge my colleagues to reject any proposal that would slash this budget in fiscal year 24. As AI continues to expand and will need to embrace and use it to take on the threats in the threat environment. So with that, I look forward to the witness's testimony. I thank the chairman for holding the hearing and I yield back. Thank you, ranking member Swalwell.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Before we get onto the witnesses without objection, I would like to allow Mr. Pfluger from Texas and Mr. Higgins from Louisiana to waive on to the subcommittee for this hearing. Okay, so moved. Other members of the committee are reminded that opening statements may be submitted. For the record, I'm pleased that four witnesses came before us today to discuss this very important topic. I ask that our witnesses please rise, raise their right hand. Do you solemnly swear that the testimony you will give before the Committee on Homeland Security of the United States House representatives will be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God, let the record reflect that the witnesses have all answered in the affirmative. Thank you. Please be seated.

I would now like to formally introduce our witnesses. First, Ian Swanson is the CEO and founder of Protect AI, a cybersecurity company for aA. Prior to founding Protect A, Mr. Swanson led Amazon web services worldwide, AI in a machine learning or ML business. He also led strategy for AI and ML products at Oracle. Earlier in his career, he also founded data science.com and was an executive at American Express Sprint and Symmetrics.

Debbie Taylor Moore is Vice President, senior partner for Cybersecurity Consulting Services at IBM. She's a 20 plus year cybersecurity executive and subject matter expert on emerging technologies and cybersecurity, including AI. Ms. Moore has also led security organizations at Secure Info, Kratos Defense, Verizon Business, and others.

Timothy O'Neill is Vice President, chief Information Security Officer, information security Officer, and product security at Hitachi Ventura, a subsidiary of Hitachi at the forefront of the information technology and operational technology convergence across multiple critical infrastructure sectors. Prior to this role, he held leadership roles at Amazon, Hewlett Packard and Blue Shield of California. Mr. O'Neill has served as law enforcement officer focused on cyber crime forensics and investigations.

Alex Stamos is the Chief Trust Officer at Sentinel One, where he works to improve the security and safety of the internet. Stamos has also helped companies secure themselves in prior roles at the Krebs Stamos Group, Facebook and Yahoo. Of note, he also advises NATO's Cybersecurity Center of Excellence, which this subcommittee had the privilege of visiting Estonia in June.

Thank you all for being here today, Mr. Swanson. I now recognize you for five minutes to summarize your opening statement.

Ian Swanson:

Good morning, members of the subcommittee on cybersecurity infrastructure protection. I want to start by thanking the chairman and ranking member for hosting this important hearing and inviting me to provide testimony. My name is Ian Swanson. I am the CEO of Protect AI. Protect AI as a cybersecurity company for artificial intelligence and machine learning. For many companies and organizations, AI is the vehicle for digital transformation and machine learning is the powertrain. As such, a secure machine learning model serves as the cornerstone for a safe AI application. Imagine there is a cake right here before us. We don't know how it got here. Who delivered it? We don't know the baker. We don't know the ingredients or the recipe. Would you eat a slice of this cake? Likely not. This cake is not just any dessert. It represents the AI systems that are becoming increasingly fundamental to our society and economy.

Would you trust AI if you did not know how it was built? If you did not know the practitioner who built it, how would you know that it is secure? Based on my experience, millions of machine learning models powering AI are currently operational nationwide. Not only facilitating daily activities, but also embedded in mission critical systems and integrated within our physical and digital infrastructure. Given the importance of these systems to a safe functioning government, I pose a critical question. If this committee were to request a comprehensive inventory of all machine learning models and AI in use in any enterprise or US government agency detailing the ingredients, the recipe, and the personnel involved, would any witness business or agency be able to furnish a complete and satisfactory response? Likely not secure. AI requires oversight and understanding of the organization's deployments. However, many deployments of AI are highly dispersed and can heavily rely on widely used open source assets essential to the AI lifecycle.

This situation potentially sets the stage for a major security vulnerability akin to the SolarWinds incident. Posing a substantial threat to national security and interests, the potential impact of such a breach could be enormous and difficult to quantify. My intention today is not to alarm, but to urge this committee and other federal agencies to acknowledge the pervasive presence of AI in existing US business and government technology environments. It is imperative to not only recognize, but also safeguard and responsibly manage AI ecosystems To help accomplish this, AI manufacturers and AI consumers alike should be required to see, know, and manage their AI risk. Yes, I believe the government can help set policies to better secure artificial intelligence. Policies will need to be realistic in what could be accomplished, enforceable, and not shut down innovation or limit innovation to just large AI manufacturers. I applaud the work by CISA and support the three secure by design software principles that serve as their guidance to AI.

Software manufacturers, manufacturers of AI machine learning must take ownership for the security of their products and be held responsible, be transparent on security status and risks of their products, and build in technical systems and business processes to ensure security throughout the AI and machine learning development lifecycle, otherwise known as ML SecOps. Machine learning security operations, while secure by design and CISA roadmap for artificial intelligence are a good foundation, it can go deeper in providing clear guidance on how to tactically extend the methodology to artificial intelligence. I recommend the following three starting actions to this committee and other US government organizations including CISA when setting policy for secure AI.

Create a machine learning bill and materials standard in partnership with NIST and other US government entities for transparency, traceability, accountability and AI systems, not just the software bill of materials and machine learning bill of materials.

Invest in protecting the artificial intelligence and machine learning open source software ecosystem. These are the essential ingredients for AI.

Continue to enlist feedback and participation from technology startups, not just the large technology incumbents.

My company Protect AI and I stand ready to help maintain the global advantage in technologies, economics, and innovations that will ensure the continued leadership of the United States and AI for decades to come. We must protect AI commensurate with the value it will deliver. There should be no AI in the government or in any business without proper security of AI. Thank you, Mr. Chairman, ranking member and the rest of the committee for the opportunity to discuss this critical topic of security of artificial intelligence. I look forward to your questions.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Thank you, Mr. Swanson. And just for the record, I probably would've eaten the cake. Ms. Moore, I recognize you for five minutes to summarize your opening statement.

Debbie Taylor Moore:

Thank you, Chairman Garbarino, Ranking Member Swalwell and distinguished members of the subcommittee. I'm very honored to be here in my 20 plus year career in cybersecurity, including working with DHS since its inception as both a federal contractor as well as a woman-owned small business leader. Let me ground my testimony by saying that the potential for AI to bolster cybersecurity for our critical infrastructure is enormous. Second, as IBM who's been engaged for more than half a century in the AI space is a leading AI company. Let me add that AI is not intrinsically high risk like other technologies, its potential for harm is expressed in both how it is used and by whom. Industry needs to hold itself accountable for the technology it ushers into the world, and the government has a role to play as well. Together we can ensure the safe and secure development and deployment of AI in our critical infrastructure, which as this subcommittee knows well underpins the economic safety and the physical wellbeing of the nation.

In fact, my clients are already taking measures to do just that. I work with clients to secure key touch points, their data, their models, and their AI pipelines, both legacy and their plans for the future. We help them to better understand, assess, and clearly define the various levels of risk that government and critical infrastructure like need to manage. For example, through simulated testing, we discovered that there are ways for adversaries to conduct efforts like derailing a train or other disruptive and disruptive types of attacks. That knowledge helped us to create preventative measures to stop it from happening in real world instances. And as the same is true for things like compromise of ATM machines and other critical infrastructure, we also conduct simulations or red teaming to mimic how an adversary could or should attack. We can apply these simulations to, for example, popular large language models to discover flaws and exploitable vulnerabilities that could have negative consequences or just produce unreliable results.

These exercises are helpful in identifying risks to be addressed before they could manifest into active threats. In short, my clients know that AI, like any technology, could pose a risk to our nation's critical infrastructure depending on how it's developed and deployed, and many are already engaging to assess, mitigate, and manage that risk. So my recommendation for the government is to accelerate existing efforts and broaden awareness and education. Rather than reinventing the wheel, first CISA should execute on its roadmap for AI and focus on three particular areas.

Number one would be education and workforce development. This should elevate AI training and resources from industry within its own workforce and critical infrastructure that it supports.

As far as the mission, CISA should continue to leverage existing information sharing infrastructure that is sector-based to share AI information such as potential vulnerabilities and best practices. CISA should continue to align efforts domestically and globally with the goal of widespread utilization of tools and automation. And from a governance standpoint to improve understanding of AI and its risks, CISA should know where the AI is enabled and in which applications. This existing AI usage inventory, so to speak, could be leveraged to implement an effective AI governance system. An AI governance system is required to visualize what needs to be protected. And lastly, we recommend that when DHS establishes the AI safety and security advisory board, it should collaborate directly with those existing AI and security related boards and councils and rationalize threats to minimize hype and disinformation. This collective perspective matters. I'll close where I started. Addressing the risks posed by adversaries is not a new phenomenon. Using AI to improve security operations is also not new, but both will require focus. And what we need today is urgency, accountability, and precision in our execution. Thank you very much.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Thank you, Ms. Moore. Mr. O'Neill, I now recognize you for five minutes to summarize your opening statement.

Timothy O’Neill:

Thank you, chairman Garbarino, ranking member Swalwell and members of the subcommittee for inviting me here today. I'm Tim O'Neill, the Chief Information Security Officer and vice President of product security at Hitachi Vantara. Hitachi Vantara is a subsidiary of Hitachi Limited, a global technology firm founded in 1910 whose focus includes helping create a sustainable society via data and technology. We co-create with our customers to leverage information technology, IT operational technology, OT, and our products and services to drive digital, green and innovative solutions for their growth. It is probably familiar to you, but OT encompasses data being generated by equipment infrastructure or a control system that can then be used to optimize the operation and for other benefits. Because of our heavy focus on the intersection of IT and OT, one of our major areas of business development and research has been in the industrial AI area.

Industrial AI has the potential to significantly enhance the productivity of US manufacturing and create working environments that benefit employees assembling products. Today's AI systems include tools that workers can use to enhance their job performance. Programs are predicting possible outcomes and offering recommendations based on the data being given to them and what the program has been trained to understand as the most likely scenario. That is true of a predictive maintenance solution. Hitachi may create for a client to help them more quickly ascertain the likely cause of a breakdown, or in the case of a generative AI system that is predicting what the next sentence could be in a maintenance manual. The US government has taken a number of positive steps over the last five years to promote and further the development of AI. We encourage the US to further the development of AI through international engagements and reaffirming the US' commitment to digital trade standards and policies and digital trade titles and treaties like the ones found in the USMCA.

The recent AI executive order EO speaks frequently to the necessity of securing AI systems. CISA's core mission focuses on cyber threats and cybersecurity, making them the obvious agency to take the lead in implementing this part of the EO. CISA is integral to supporting and providing resources for other agencies on cyber threats and security as those agencies then focus on their roles in implementing the executive order. This mission is vital to the federal government and where CISA is by far the expert. We applaud the CISA team for their excellent outreach to stakeholders and private industry to understand implications of security threats and help carry out solutions in the marketplace. Their outreach to the stakeholder community is a model for other agencies to follow. As CISA's expertise lies in assessing the cyber threat landscape, they're best positioned to support the AI EO and help further development of AI innovation in the us.

As CISA continues its mission, we recommend focusing on the following areas to help further the security of AI systems. One, work across agencies to avoid duplication, duplicative requirements that must be tested or complied with. Two, focus foremost on the security landscape being the go-to agency for other federal agencies as they assess cyber related AI needs. Three, be the agency advising other agencies on how to secure AI or their AI testing environments. Four, recognize the positive benefits AI can bring to the security environment, detecting intrusions, potential vulnerabilities, and or creating defenses. Hitachi certainly supports ongoing cybersecurity work. CISA's roadmap for AI has meaningful areas that can help promote the security aspects of AI usage. Avoiding duplicating the work of other agencies is important, so manufacturers do not have to navigate multiple layers of requirements. Having such a multilayered approach could create more harm than good and divert from CISA’s well-established and much appreciated position as a cybersecurity leader. It could also create impediments for manufacturers, especially small and medium sized enterprises, from adopting AI systems that would otherwise enhance their workers' experience and productivity, improve factory safety mechanisms and improve the quality of products for customers. Thank you for your time today, and I'm happy to answer any questions.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Thank you, Mr. O'Neill. Mr. Stamos, I now recognize you for five minutes to summarize your opening statement.

Alex Stamos:

Hey, thank you, Mr. Chairman. Thank you, Mr. Swalwell, I really appreciate you holding this hearing and inviting me today. So I'm the Chief Trust Officer of SentinelOne. I've had the job for about a month, and in that role I've got two responsibilities. So Sentinel is a company that uses AI to do defense. We also work with companies directly to help them respond to incidents, and so I get to go out in the field and work with companies that are being breached, help them fix their problems, but then I'm also responsible for protecting our own systems because security companies are constantly under attack these days, especially since the SolarWinds incident.

What I thought I'd do is, if we're going to talk about the impact of AI and cybersecurity, just set the stage of where we are in the cybersecurity space and where American companies are right now so we can have an honest discussion about what AI, the effects might be.

And the truth is, we're not doing so hot, we're kind of losing. We talk a lot in our field about the really high-end actors, the state actors, the GRU, the FSB, the MSS, the folks that you guys get classified briefings on, and that's incredibly important, right? Just this weekend we learned more about Volt Typhoon, a Chinese actor breaking into the Texas power grid, a variety of critical infrastructure providers that is scary and something we need to focus on. But while that very high end stuff has been happening, something much more subtle has been occurring that's kind of crept up on us, which is the level of adversity faced by kind of your standard mid-sized company, the kind of companies that honestly employ a lot of your constituents, 5,000 employees, 10,000 employees successful in their field, but not defense contractors or oil and gas or banks or the kinds of people who have traditionally had huge security teams.

Those kinds of companies are having an extremely difficult time because of professionalized cybercrime. The quality of the cyber criminals has come up to the level that I used to only see from state actors four or five years ago. So now you will see things out of these groups, the black cats, the alphas, the lock bits, the kinds of coordinated specialized capabilities that you used to only see for hackers working for the Ministry of State Security or the Russian SVR. And unfortunately, these companies are not ready to play at that level. Now, the administration has done some things to respond to this. As you all know, there have been sanctions put in place to make paying ransoms to certain actors more difficult. That strategy, I understand why they did it. I'm glad they did it, but it has failed the current strategy of sanctioning. All it has done is created new compliance and billable hour steps for lawyers before ransom is paid.

It hasn't actually reduced the amount of money that is being paid to ransomware actors, which is something on the order of over $2 billion a year being paid by American companies to these actors. That money, then they go reinvest in their offensive capabilities. While this has been happening, the legal environment for these companies has become more complicated. You folks in Congress passed a law in 2022 that was supposed to standardize, how do you tell the US government that somebody has broken into your network? That law created a requirement for CISA to create rules. Now, it's taken them a while to create those, and I think it would be great if that was accelerated. But in the meantime, while we've been waiting for CISA to create a standardized reporting structure, the SEC has stepped in and created a completely separate mechanism and requirements around public companies that don't take into account any of the equities that are necessary to be thought of in this situation, including having people report within 48 hours, which from my perspective, usually at 48 hours, you're still in a knife fight with these guys.

You're trying to get them out of the network. You're trying to figure out exactly what they've done. The fact that you're filing 8Ks in Edgar that says exactly what you know and the bad guys are reading it, not a great idea, and some other steps that've been taken by the SEC and others has really over legalized the response companies are taking. And so as we talk today, I hope we can talk about the ways that the government can support private companies. These companies are victims. They're victims of crime or they're victims of our geopolitical adversaries attacking American businesses. They are not there to be punished. They should be encouraged. They should have requirements for sure, but when we talk about these laws, we also need to encourage them to work with the government and the government needs to be there to support them. Where does AI come into this?

I actually think I'm very positive about the impact of AI on cybersecurity. Like I said, these normal companies now have to play at the level Lockheed Martin had 10 years ago. When I was the CISO of Facebook, I had an ex-NSA malware engineer. I had threat intel people that could read Chinese, that could read Russian. I had people who had done instant responses at hundreds of companies. There is no way an insurance company in one of your districts can go hire those people. But what you can do through AI is we can enable the kind of more normal IT folks who don't have to have years of experience fighting the Russians and the Chinese and the Iranians. We can enable them to have much greater capabilities, and that's one of the ways I think AI could be really positive. So as we talk about AI today, I know we're going to talk about the downsides, but I also just want to say there is a positive future here about using AI to help normal companies defend themselves against these really high end debtors. Thank you so much.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Thank you, Mr. Stamos. And like you, I agree that the SEC rule is terrible. Yeah, and hopefully the Senate will fix that this week. We can take it up in January. Members will be recognized by order of seniority for their five minutes of questioning, and an additional round of questioning may be called After all the members have been recognized. I now recognize I'm not going to go into seniority. I'm going to go with Mr. Luttrell from Texas for five minutes.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. Thank you all for being here today. This is definitely a space that we need to be operating in from now to the very extensive future. Mr. Stamos, you brought up a very valid point. It's the lower entities. I had a hospital get hit in my district the day after we had a CISA briefing in the district. My question is, because people show up after the attack happens, we have, and I would say it's inevitably when you peel this onion back, it's the human factor that more or less its the problem set because we can't keep up with the advances in AI every second of every hour of every day. It's advancing, and it seems like because the industry is very siloed, AI ML is very siloed depending on the company you work for, as we try to secure artificial intelligence and we have that human factor, my question is, and this may even sound silly, but again, I don't know what I don't know. Can AI itself secure AI? Is there any way that we can remove as much error as possible and have artificial intelligence work to secure artificial intelligence? Because as humans, we can't work that fast? Does that question at all makes sense? Mr. Stamos, you start that.

Alex Stamos:

Yes, absolutely, sir. I think it does make sense. I think where we're going to end up is we're moving out of a realm. This stuff is happening so fast where human reaction time is not going to be effective anymore, correct? Yes. And it is going to be AI v AI, and you'll have humans supervising training, pushing the AI in the right direction on both the defender side and the attacker side.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

Is there anything that lives out there right now in the AI ML space that's combating it, and I dare not say on its own, I don't want to talk about the singularities and scare people out of their clothes, but are we even remotely close? I agree with the other statement you said we're behind on this one.

Alex Stamos:

Yeah, so there's a bunch of companies, including our own, that use AI for defensive purposes. Most of it right now is one of the precepts of modern defense in large networks is you gather up as much telemetry data, you suck as much data as possible into one place, but the problem is having humans look at that as effectively impossible. And so using AI to look through the billions of events that happen per day inside of a medium-sized enterprise is what is happening right now. The problem is the AI is not super inventive yet, and I think that's where we're looking as defenders to make it more creative and more predictive of where things are going and better at noticing things, weird attacks that have never been seen before, which is still a problem.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

And how do we even see something at that speed? I mean, we're into exascale computing, if I'm saying that correctly, how does the federal government model and scale this in order to support our industry?

Ian Swanson:

Yeah, it is a great question. I think we need to boil it down though to the basics in order to build–

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

I'm all about that. Absolutely. Yeah, please.

Ian Swanson:

And I think the simplest things need to be done first, and that is we need to use and require a machine learning bill of materials, so that record, that ledger. So we have provenance, so we have lineage, so we have understanding of how the AI works.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

Is it even possible to enclave that amount of retrospective prospective data?

Ian Swanson:

It is. It is. And it's necessary.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

I believe it's necessary, but even I don't even know what that looks like. We have 14 national laboratories with some of the fastest computers on the planet. I don't think we’ve touch it yet.

Ian Swanson:

And as I said, I think there are millions of models live across the United States, but there definitely is software from my company and others that are able to index these models and create bills of materials. And only then do we have visibility and auditability to these systems, and then you can add security.

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

How do we share that with Rosie's Flower Shop in Magnolia Texas?

Ian Swanson:

I think that's a challenge, but we're going to have to work on that. That's something we're trying to figure out to go down with all of you and say, how do we bring this down to small, medium-sized businesses and not just the large enterprises and the AI incumbents?

Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-TX):

I have 30 seconds, I'm sorry I can't get to each and every one of you, but I would really like to see a broken out infrastructure on the viability of threats and the attack mechanism that we can populate or support at our level to get you what you need.

We can't see at that speed that is just, and I don't think people can appreciate the amount and just the sheer computational analytics that go into where we are right now, and we are still in our infancy, but if we had the ability to, if you can put it in crayon for me, it's even better. So we can understand and not only speak and we understand we can speak to other members, this is why this is important and this is why we need to move in this direction in order to stay in front of the threats. But thank you, Mr. Chairman. I yield back.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Gentleman yields back. I now recognize the ranking member, Mr. Swalwell from California for five minutes.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Great, thank you, chairman. And like every witness, I share in the excitement about the potential of AI, and one piece of this that is not discussed enough is equity in AI and making sure that every school district in my district gives a child the opportunity to learn it. And I think that's one part we have to get right, is to make sure that you don't have two classes of kids, the class that learns AI and the class that doesn't have the resources. That's a separate issue. But on cybersecurity, Mr. Stamos, if you could just talk about what can AI do on the predictive side to help small and medium sized businesses to kind of see the threats that are coming down the track and stopping them, and is that affordable right now? Is it off the shelf? How do they do that?

Alex Stamos:

Yeah, so I think this is related to Mr. Luttrell's flower shop. He's talking about if you're a smaller or medium-sized business, it has never been either cost effective or really honestly possible to protect yourself at the level that you're dealing with by yourself. And so I think the way that we support smaller, medium businesses is we try to encourage one, to move them to the cloud as much as possible. Effectively, collective defense. If your mail system is run by the same company that's running a hundred thousand other companies and they have a security team of four or 500 people that they can amortize across all those customers, that's the same thing with ai. And then the second is probably to build more–we're called MSSP, managed security service provider relationships, so that you can go hire somebody whose job it is to watch your network and that they give you a phone call and hopefully if everything's worked out and the AI has worked out, you get a call that says, oh, somebody tried to break in. They tried to encrypt your machine. I took care of it.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

And what can CISA do to work with the private sector on this?

Alex Stamos:

So I like what CISA has done so far. I mean, I think their initial guidelines are smart. CISA, like I said before, I think a key thing for CISA to focus on right now is to get the reporting infrastructure up. One of the problems we have as defenders is we don't talk to each other enough. The bad guys are actually working together. They hang out on these forums, they trade code, they trade exploits. But when you deal with a breach, you're often in a lawyer imposed silo that you're not supposed to talk to anybody and not sending any emails and not working together. And I think CISA breaking those silos apart so that companies are working together is a key thing they can do.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Do you see legal risks that are bending companies away from smart transparent responses?

Alex Stamos:

Yeah, unfortunately. Something I put in my written testimony, I once worked in instant response where there were four law firms on every single call because different parts of the board were suing each other and there's a new CEO and an old CEO, and it was a mess. You can't do instant response to a situation where it's all overly legalized. And I think part of this comes from the shareholder stuff, is that any company that deals with any security breach, any public company automatically ends up with derivative lawsuits that they spend years and years defending that don't actually make anything better. And then part of it is the regulatory structure of the SEC and such, creating rules that kind of really over legalize defense.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Do we have the talent pool or the willingness of individuals right now to go into these fields to work as a chief information security officer?

Alex Stamos:

So we have a real talent pool problem on two sides, so on, I don't want to say the low end, but the entry-level jobs. We are not creating enough people for the SOC jobs, the analyst jobs, the kinds of things that most companies need. And I think that's about investing in community colleges and retraining programs to help people get these jobs, either mid-career or without going and doing a computer science degree, which really isn't required for that work. And then at the high end, chief information security officer, CISO is the worst C-level job in all of public capitalism.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Why is that?

Alex Stamos:

Sorry sir. Because it is–you are naturally, when I was a CISO and I would walk in the room, people would mutter under their breath like, oh my god, Stamos is here. And it's partially because you're kind of the grim reaper, right? You're only there for negative downside effects for the company. You have no positive impact on the bottom line generally. And so it's already a tough place, but what's also happened is that there's now legal actions against CISOs for mistakes that have been made by the overall enterprise. And this is something else I'm very critical of the SEC about is that they're going after the CISO of SolarWinds.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

Is that a deterrent to people wanting to be a CISO?

Alex Stamos:

Oh, absolutely. I have two friends this last month who have turned down CISO jobs because they don't want the personal liability. They don't want to be in a situation where the entire company makes a mistake and then they're the ones facing a prosecution or an SEC investigation. It's become a real problem for CISOs.

Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA):

I yield back. Thanks.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Gentlemen yields back. I now recognize my friend from Florida, Mr. Gimenez for five minutes of questioning.

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I just asked my chat on if there are AI systems right now actively protecting computer systems in the United States and around the world and it said yes. So you do have the rudimentary aspects of AI because some months ago we were at a conference or at least a meeting with a number of technologists, Google, Apple, all those, and I asked them a question in terms of AI, where are we? And imagine that 21 being an adult, and where are we in that race? And they refused to answer and give me an age. What they did do though, they said we're in the third inning. So baseball analogy, nine innings is the full game. So we're one third of the way there, which is kind of scary because of the capabilities right now that I see are pretty scary. So at the end of the day, do you think this could all be elementary? I mean, it appears to me that what we're heading for is cyber attacks are going to be launched by artificial intelligence networks and they're going to be guarded against by artificial intelligence networks and that it's who has the smartest artificial intelligence is going to win the race or is going to win out in that battle or war, etc. Would that be accurate? Yeah, anybody?

Alex Stamos:

Yes, sir, that's absolutely accurate.

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

And so now it means that we have to win the artificial intelligence battle, or is this just going to be a race that's going to be forever?

Alex Stamos:

Yes. I mean, I think basic economic competitiveness is absolutely dependent on us maintaining our lead in overall AI technologies, but then especially AI technologies that are focused on cybersecurity.

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

Where do you see the future? Am I too far off? It's just going to be machines going at each other all the time, testing each other, probing each other, defending against each other, and then somebody will learn a little bit more and get into one system and then that system learns and combats the next one. But is this just going to be continuous round the clock cyber warfare?

Alex Stamos:

Yeah, unfortunately, I think that's the future we're leading to. I mean, it was seven years ago in 2016, DARPA ran an event which was about teams building computers that hacked each other without human intervention, and that was successful. And so we're seven years on from that kind of basic research that was happening. I'm very afraid of the constant attacks. The other thing I'm really afraid of is smart AI enabled malware that you look at the Stuxnet virus that the US has never admitted to have been a part of, but whoever created Stuxnet spent a huge amount of money and time building a virus that could take down the Natanz nuclear plant. And it required a huge amount of human intelligence because it was specifically built for exactly how Natanz’s network was laid out. My real fear is that we're going to have AI generated malware that won't need that. If you drop it inside of an air gap network in a critical infrastructure network, it will be able to intelligently figure out, oh, this bug here, this bug here, and take down the power grid. Even if you have an air gap,

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

This is just conjecture. Okay, could we ever come to the point that we say, what the heck? Nothing is ever going to be safe and therefore chuck it all and say, we're going to go back to paper and we got to silo all our stuff. Nothing can be connected anymore because anything that's connected is vulnerable. All our information is going to be vulnerable no matter what we do. That eventually somebody will break through and then we're going to be at risk. Is it possible that in the future we just say, okay, enough, we're going back to the old analog system? Is that a possibility?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

I'd like to answer that. I think that in our industry in general, we have a lot of emphasis on the front end of detection of anomalies and findings and figuring out that we have vulnerabilities and trying to manage threats and attacks. And I think there's less so on resilience because bad things are going to happen. But what is the true measure is how we respond to them. And AI does give us an opportunity to work toward, how do we reconstitute systems quickly? How do we bounce back from severe or devastating attacks and with critical infrastructure that's physical as well as cyber? And so when you look at the solutions that are in the marketplace in general, the majority of them are on the front end of that loop. And the backend is where we need to really look toward how we prepare for the onslaught of how creatively attackers might use ai.

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

Okay. Thank you. My time is up and I yield back.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Gentlemen yields back. I now recognize Mr. Carter from Louisiana for five minutes of questioning.

Rep. Troy Carter (D-LA):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman, and thank all of the witnesses for being here. What an exciting content and as exciting it is, is the fear of how bad it can be. What can we learn from the lack of regulation and social media, Facebook and others on the front side that we can do better with AI, Ms. Moore?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

Well, I think that there are many lessons to be learned. I think that, first of all, from a seriousness perspective, I think that AI has everyone's attention now that it's disintermediated, sort of by all the middle people and it's directly in the hands of the end users. And now folks have workforce productivity tools that leverage AI. We have been using AI for years and years. Anybody here who has a Siri or Alexa, you're already in the AI realm. The piece that we have to consider is one of the points that Congressman Swalwell brought up around the idea of education and upskilling and making sure that people have the skills in AI that are necessary to become part of this future era. We work to train folks. We were training over 2 million people over the next three years strictly in AI. We've all got to upskill. This is all of us collectively. And I think also a point was brought up about the harmonization piece. I think that this is one area that we can all agree that if we aren't expedient in the way we approach it, that it's going to run right over us.

Rep. Troy Carter (D-LA):

So let me re-ask that. Thank you very much. But what I really want to know is we're here. It's here. How can we learn and how can we regulate it better to make sure that what has so much power and so much potential to be good, we thwart the bad part. One of the example I recently saw on social media a few weeks ago, a message from what looked like, sounded like the president of the United States of America, giving a message now to the naked eye, to the individual that's out there that's not paying attention to the wonders of AI, that was the president. How do we manage that from a security risk? How do we know that this person that's purporting to be secretary mayor is telling us about a natural disaster or a security breach? Isn't some foreign actor any one of you, in fact, everyone, quickly, we have about two minutes, Mr. Stamos.

Alex Stamos:

So on the deep fakes for political disinformation, I mean, I think one of the problems now is it is not illegal to use AI to create. There's no liability of creating totally real things that say embarrassing things that are used or political. It's totally legal to use AI and political campaigns and political advertising for the moment, right? So I would start there and then work your way down. I think the platforms have a big responsibility here to try to detect, but it turns out detection of this stuff is a technical challenge.

Rep. Troy Carter (D-LA):

Mr. O'Neill.

Timothy O’Neill:

I was going to say, if we could focus on the authentication and giving consumers and the public the ability to validate easily the authenticity of what they're seeing, that would be important. And the other thing that was talked about, which I agree with Ms. Moore about the backend is making sure that we have these resilient systems. What we've learned with social media and cybersecurity in general is it's an arms race. It always has been. It always will be. And we're always going to be defending and spy versus spy type activities trying to outdo each other. We need to make sure that we have the backend systems, the data that's available, the ability to recover quickly and get to normal operations. Backup.

Rep. Troy Carter (D-LA):

We've got about 40 seconds. Thank you very much, Ms. Moore, did you have any more to add? And then I want to get to Mr. Swanson.

Debbie Taylor Moore:

I'd just say that there are technologies available today that do look at sort of defending reality, so to speak, but that disinformation and the havoc that it wreaks is an extreme concern. And I think that the industry is evolving.

Ian Swanson:

From a manufacturer of AI perspective, we need to learn and we need to understand that AI is different from typical software. It's not just code. It's data. Yes, it's code. It's a very complex machine learning pipeline that requires different tactics, tools, and techniques. In order to secure it, we need to understand and we need to learn that it's different in order to secure AI.

Rep. Troy Carter (D-LA):

And the disadvantage that we have is oftentimes the bad actors are moving as fast, if not faster than we are. So we stand ready, particularly from this committee standpoint, to work closely with you to identify ways that we can stay ahead of the bad actors and make sure that we're protecting everything from universities to bank accounts to political free speech. There's a real danger. So thank you all for being here. Mr. Chairman, I yield back.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Gentleman yields back. I now recognize Ms. Lee for five minutes from Florida.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. Yesterday, it was widely reported that China launched a massive attack, a cyber attack against the United States and our infrastructure. This incident is just one single event in a decades long cyber warfare campaign launched against the United States. We should not expect these threats to lessen and should continue to engage with the proper stakeholders to determine how best to defend our infrastructure. And one of the things that's so important is what each of you has touched on here today, how artificial intelligence is going to empower and equip and enable malicious cyber actors to do potential harm to the United States and our infrastructure. I'd like to start by returning to something you mentioned, Mr. Stamos. I was interested in this point during your testimony with Mr. Gimenez, you described a scenario where artificial intelligence malware could essentially deploy within critical infrastructure on an air gap network. Can you share with us a little bit more about how you visualize that threat occurring? How would it get to the air gap network in the first place?

Alex Stamos:

Right. So the example I was using is the most famous example of this is Stuxsnet, where the exact mechanism, where the jump to air gap has not been totally determined, but one of the theories is that Stuxnet was spread pretty widely among the Iranian population. And somebody made a mistake, they charged a phone, they plugged in their iPod at home, and then it jumped on the USB device into the network. And so there are constantly, whenever you work with secure air gap networks, there are constant mistakes that are being made where people hook them up, people bring devices in, stuff like that.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

Thank you. And Ms. Moore, I'd like to go back to your point when you talked about really the inevitability, that there will be incidents, that there will be vulnerabilities, and that one of the things that we can do that's most productive is to focus on resilience, recovery, rebuilding. You've had unique experience working before in federal government on several cybersecurity initiatives. Would you share with us your perspective on how DHS and CISA can best be thinking about those concepts and how we should be measuring success and performance in that way?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

That's a very good question. I think that one of the things that we have to move away from in general is measuring based on compliance and the knowledge only that we have around what we know is a known threat. And so again, the way I said earlier that we spend a lot of time cataloging all of our concerns. And I think that when you look at industry and you look at industry globally, and you look at the power of AI and you consider the way that we manage markets today, the way that we have transactional data moving all over the globe and in context, and we have the ability to have that information in front of us in real time, that's the way security needs to be. That's the way threat intelligence needs to be. It needs to be that way across all sectors, but curated for the specific sector. And so it'd be a way of sort of having a common record of knowledge amongst all of the critical infrastructure players and DHS and the FCEBs and something that we could rely on that would be expedient in helping us to at least stay ahead of the threat.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

And as far as the EO itself that directs DHS to develop a pilot project within the federal civilian executive branch systems, is there any specific information that you think would be helpful for DHS and CISA to share with the private sector as they determine lessons learned from the pilot?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

For me, yes. I think that there is extreme importance around what we consider to be iterative learning in the same way that AI models go out and they train themselves, literally train themselves iteratively, we need to do the same thing. So in so many instances throughout global enterprises, everywhere we have lessons learned, but they're not always shared completely nor do we model these threats in a way that we learn collectively where the gaps are and do that consistently.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

And Mr. O'Neill, a question for you. Do you find that generally companies in the private sector are considering the cybersecurity background risk profile of artificial intelligence products when deciding whether to use them? And how can CISA better encourage that type of use of AI that is secured by design?

Timothy O’Neill:

Thank you for the question. I'm a big fan of CISA, especially with the guidance, the tactical and strategic information they're providing to businesses about threat actors and so forth. And they're secure by design. One of the things they call for is doing threat modeling. And when you're designing applications and systems and so forth, if you're doing the threat modeling, you're basically now having to contend with and understand that you're going to be attacked by automated systems or having AI used against you. So I think that helps. Sorry, dunno what that is. Oh.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

Not to worry.

Timothy O’Neill:

That would be one thing. The other thing I would recommend to CISA would be they're very focused on giving great information about the type of exploits that attackers are using, and it really helps with defenses and so forth. But again, if they could take some of that leadership focused on resiliency, preparedness, and recovery so that the companies, it's a matter of time that you will likely have an event. It's how you are able to respond to that event. And there's many companies, such as the one that I work for that help companies prepare for the inevitable event to be able to recover and so forth. But having the workaround procedures, especially for critical infrastructure to get that working and functional so that it can carry out its mission while the recovery occurs, that type of thing. And having your data secured so that it's available and before the attackers got to it, encrypted it and you can go to a known good copy and stuff is very important. I think they could expand their scope a little more to help companies to be able to really have the workaround procedures and the testing and so forth, just like they do the red team testing to find the vulnerabilities and try to prevent the issues. But also on the backside to recover and learn from the incidents to drive continuous improvement. Thank you.

Rep. Laurel Lee (R-FL):

Thank you, Mr. O'Neill. Mr. Chairman, I yield back.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Not a problem. I'll just deduct that extra time from Mr. Menendez. I now recognize Mr. Menendez from New Jersey for three and a half minutes.

Rep. Rob Menendez (D-NJ):

I appreciate that, Mr. Chairman. And I'd always be happy to yield to my colleague from Florida who's one of the best members of this subcommittee, and I always appreciate her questions and insight. Mr. Chairman, Mr. Ranking Member, thank you for convening today's hearing. To our witnesses, thank you for being here. I want to talk about one of the fundamental structural issues with AI, how it's designed can lead to discriminatory outcomes. These types of generative AI that have captured public attention over the last year produce content based on vast quantities of data. Here's the problem. If those vast quantities of data, those inputs are biased, then the outcome will be biased as well. Here are a few examples. The Washington Post published a story last month about how AI image generators amplify bias in gender and race. When asked to generate a portrait photo of a person in social services, the image generator, Stable Diffusion XL, issued images exclusively of non-white people. When asked to generate a portrait photo of a person cleaning all of the images were of women. In October, a study led by Stanford School of Medicine researchers was published in the Academic journal Digital Medicine that showed that large language models could cause harm by perpetuating debunked racist medical ideas. These questions are for any of our witnesses. How can developers of AI models prevent these biased outcomes?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

First of all, in terms of both from a security standpoint as well as from a bias standpoint, all teams need to be diverse. And let me just say that from a security standpoint, when we're doing things like red teaming and we're going in and assessing vulnerabilities, we need a team of folks that are not just security people. We need folks who are also very deep in terms of subject matter expertise around AI and how people develop models, train models associated with malware that is adaptive maybe in nature, but those teams don't look like our traditional red teaming teams. On the bias front, the same thing. The data scientists, developers, and folks that are building the models and determining the intent of the model need to look like everybody else who is impacted by the model. And that's how we move further away from disparate impact, where groups are impacted more than others.

Algorithms control who gets into what school, what kind of insurance you have, where you live, if you get a mortgage, all of these things, these are very important things that impact our lives. And so when folks are building models, the intent of the model and the explainability of the model, being able to explain the purpose where the data came from and attribute those sources, being able to ensure that that model is ethical, these are all things that security may be able to point out to you the problem, but the tone is at the top of the organization in terms making.

Rep. Rob Menendez (D-NJ):

I want to follow up with you and then I'll circle back to any of the other witnesses on that first question, but that's a question that we've sort of grappled with on this committee is one, just the workforce development within the cyber community and what that looks like and then ensuring, especially with AI, as you alluded to in your answer, that it's reflective of the larger community. In your opinion, how do we build teams? How do we grow the cyber workforce? So it's a diverse group of individuals that can bring these backgrounds into the cyber career?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

Well, I think it's commitment. I know that IBM, for instance, has stood up 20 HBCU cybersecurity centers across 11 states, and this is all at no additional cost to the folks who will get this training. I think that AI is not unlike cybersecurity. I think that when we look at the threats associated with ai, it's just an expansion of the attack surface. And so we really need to treat this not as a completely, totally different thing, but employ the tactics that have worked in educating and training people and ensuring that there is not a digital divide in AI and quantum and cybersecurity and all of the emerging technology areas. And I also think that a best practice is to implement these things K through 12 to start when folks are very young and as they grow and as the technologies evolve, the knowledge can be evolving as well.

Rep. Rob Menendez (D-NJ):

I agree with that approach and would love to build that from an earlier age. I have to pivot real quickly. One of the things that I want to focus on is less than a year before the 2024 election, we see the potential for generative ai increasingly likely spreading misinformation with respect to our elections for any of the witnesses. What specific risk does AI pose to election security?

Alex Stamos:

I think there's too much focus on a specific video or image being created of a presidential candidate. If that happened, every media organization in the world would be looking into whether it's real or not. I think the real danger from AI in 2024 and beyond, and again, you've got India, you've got the EU, there's a ton of elections next year. The real problem is it's a huge force multiplier for groups who want to create content. If you look at what the Russians did in 2016, they had to fill a building in St. Petersburg with people who spoke English. You don't have to do that anymore. A couple of guys with a graphics card can go create the same amount of content on their own. And that's what really scares me is that you'll have groups that used to not have the ability to run large professional troll farms to create all this content, the fake photos, the fake profiles, the content that they push that now a very small group of people can create the content that used to take 20 or 30.

Rep. Rob Menendez (D-NJ):

And it'll be quickly shared right through social media. So your force multiplier is exactly right, not just the production, but the sharing quality as well rapidly increases ] the spread of it. And that's going to be a challenge. I wish I had more time, but the chairman distracted me at the beginning of my line of questioning, so I have to yield back the time that I don't have. Thank you.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

You're not allowed to take time from me, so it's all right. I believe we're going to do a second round because this is so interesting. So gentlemen yields back time that he didn't have.

I now recognize myself for five minutes of questions. Ms. Moore, Mr. O'Neill brought up red teaming in one of his answers before, and I understand CISA as tasked in the executive order with supporting red teaming for generative AI. Do you believe CISA has the expertise and bandwidth necessary to support this? And what would a successful red teaming program look like?

Debbie Taylor Moore:

I think that CISA is like everyone else. We're all looking for more expertise that looks like AI expertise in order to be able to change the traditional red team. With a traditional red team, the important piece of this is that, so you're essentially testing the organization's ability to both detect the threat and also how does the organization respond. And these are real world simulations. And so once you've established that there are gaps, the hard part is remediation. The hard part is now I need more than the folks that have looked at all of this from a traditional security standpoint, and I need my SMEs from the data scientists data engineer perspective to be able to help to figure out how to remediate. And when we are talking about remediation, we're back to where we started in terms of this discussion around, we have to close the gaps so that they are not penetrated over and over and over again.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

So I guess there's a concern that if we find the weakness, it might not be the knowledge to fix it.

Debbie Taylor Moore:

We have to upskill.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Okay. Mr. O'Neill, another question about the EO. CISA's tasked with developing sector specific risk assessments in the EO, but I understand there are many commonalities or similar risks across sectors. How can CISA ensure that it develops helpful assessments that highlight unique risks for each sector? And would it make more sense for CISA to evaluate risk based on use cases rather than sector by sector?

Timothy O’Neill:

I believe CISA needs to take approach like they've done in other areas, and it's a risk-based approach based on the use case within the sector because you're going to need a higher level of confidence for an artificial system that may be used in connection with critical infrastructure and making decisions versus artificial intelligence that would be used to create a recipe or something like that for consumers. But the other thing where CISA could really help again is the secure by design in making sure that when you're doing threat modeling, you're not only considering the malicious actors that are out there, but also the inadvertent errors that could occur that would introduce bias into the artificial model, artificial intelligence model. Thank you.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

So you've just said it, they've done this before. So there are existing risk assessment frameworks that CISA can build off of. What would they be? And that's for anybody if anybody has the answer there.

Debbie Taylor Moore:

I'll take that one. I think that one that is tremendous is Mitre Atlas. Mitre Atlas has all attacks associated with AI that are actually real world attacks and they do a great job of breaking them down according to the framework. Everything from reconnaissance to discovery to tying and mapping the activities of the bad actor to their tactics, techniques and procedures, and giving people sort of a roadmap for how to address these from a mitigation standpoint, how to create countermeasures in these instances. And the great part about it is that it's real world, it's free. It's right out there on the web. And I would also say that one other resource that CISA has at its disposal, which is very good, is the AI RMF, the risk management framework, the playbooks are outstanding. Now there's the risk management framework, but the playbooks literally give folks an opportunity to establish a program that has governance.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Mr. Swanson, CISA's AI roadmap details, a plan to stand up a JCDC for AI. This committee has had questions about what CISA does with the current JCDC, and we haven't gotten them all answered, but they want to do this JCDC for AI to help share threat intel related ai. How do you share information with CISA currently, and what would be the best structure for JCDC.AI, what would that look like?

Ian Swanson:

Yeah, thanks for the question. Like my fellow testimonial givers up here, we talked about the sharing of information and education is going to be critical in order for us to stay in front of this battle, this battle for securing AI. You asked specifically, how is my company sharing? We actually sit in Chatham Health rules events with Mitre, with NIST, with CISA in the room, and we share techniques that adversaries are using to attack these systems. We share exploits, we share scripts, and I think more of this education is needed and also amongst the security companies that are up here so that we can better defend against AI attacks.

Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY):

Thank you very much. My time is up. I think we're going to start a second round. I will now recognize, I believe second round we start with Mr. Gimenez for five minutes.

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I'm going back to my apocalyptic view of this whole thing. Okay. And I guess I may have been influenced by Arnold Schwarzenegger in those movies with Coming from the Future and these machines battling each other. And I think that it's not too far off. I mean it's not going to be like that, but I'm saying the machines battling each other is going to be constant. So the artificial intelligence, battling the artificial intelligence until the one that is dominant will defeat one and penetrate and defeat the system, whether it's the aggressor or the defender, which to me makes it much more important that we are resilient and that we're not wholly dependent on anything. And instead of becoming more and more dependent on these systems, we become less dependent. Yes, it's nice to have, as long as they're working, you're great, but you have to assume that one day they won't be working and we have to continue to operate.

So where are we in terms of resiliency, of the availability of us to decouple critical systems vital to America, our electric grid would be one, our piping would be another, et cetera. All those things that are vital to our everyday life where CISA is trying to get companies and the American government to be able to decouple or extract itself from the automated systems and still give us the ability to operate because I do believe that every one of those systems eventually will be compromised, eventually will be overcome, eventually will be attacked and we may find ourselves in really bad shape, especially if it's an overwhelming kind of attack to try to cripple the America. So does anybody want to tackle that one? Because we seem to be looking more and more about how we can defend our systems, and I believe that that's great, but those systems are going to be compromised one day. They're going to be overwhelmed one day. So we have to have a way to not be so dependent on those systems so that we can continue to operate.

Debbie Taylor Moore:

I think that one of the things that with any sort of preparation for the inevitable or preparation for potential disaster or catastrophe if you will, really is rooted in exercises. I think that from an exercise perspective, we have to look at where we are vulnerable certainly, but we have to include all the players. And it's not just the systems that get attacked, but also everything from every place within the supply chain as well as emergency management systems, as well as municipalities and localities. And I think that one of the things that CISA does so well is around PSAs for instance. And I know that this is sort of like a first step in this realm. And what I mean by that is, does the average American know exactly what to do if they go to the ATM and it's failed or if their cell phone is not working or if they can't get–

Carlos Gimenez (R-TX):

No, the cell phone is not working. We're done.

Debbie Taylor Moore: