To Move Forward with AI, Look to the Fight for Social Media Reform

Camille Carlton, Jamie Neikrie / May 25, 2023Camille Carlton is the Senior Policy Manager at Center for Humane Technology, and Jamie Neikrie is the legislative lead for the Council for Responsible Social Media, an initiative of Issue One.

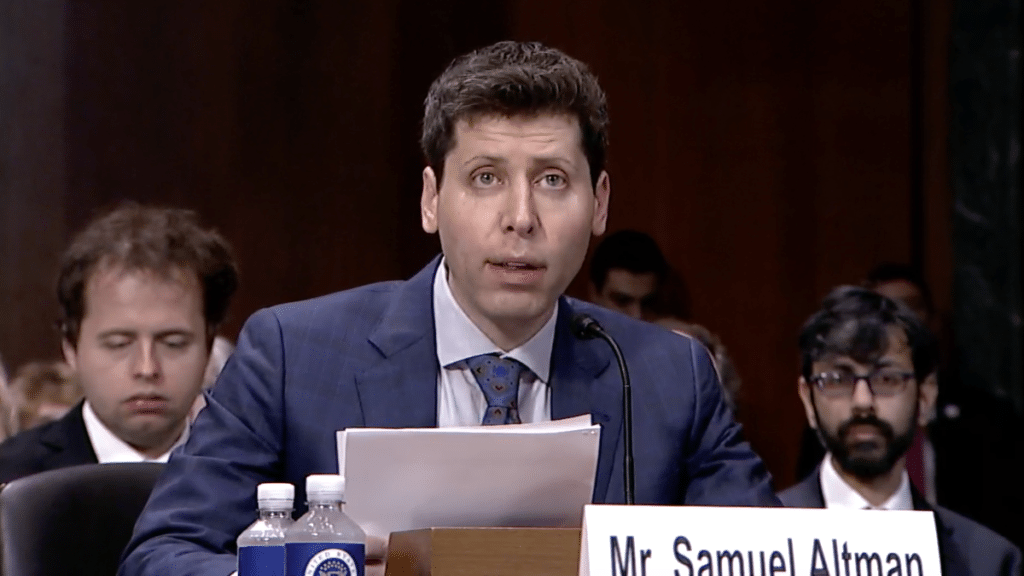

Last week’s Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on Oversight of AI united members across the aisle in a shared sense of urgency — Congress must move quickly to address the new capabilities and threats posed by generative artificial intelligence. Underlying this consensus was the sentiment that we cannot make the same mistakes we made with social media when it comes to AI. As Committee Chair Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) stated in his opening remarks, “Congress failed to meet the moment on social media. Now we have the obligation to do it on AI before the threats and the risks become real.”

We have a narrow window before the new wave of generative AI products become so deeply entangled with society, the economy, and politics that they are largely beyond accountability, as social media has become. So how can we keep from repeating history? We have to first look back: in order to understand how AI builds on previous technological advances and to extract key lessons from the push for social media oversight.

General Purpose AI, Generative AI, and How We Got Here

General purpose AI systems are designed to perform a wide range of tasks. These systems have been trained on broad sets of unlabeled data, allowing them to function across a significant set of use cases. Today, general-purpose AI has become mainstream in the form of generative AI technologies; systems that are capable of generating new, increasingly realistic content, such as text, images, or audio.

These models are trained to look at a user’s prompt and ask, again and again, “given the input so far, what should the next output be?” This process might sound simple, but it means that AI models can be led (or lead the user) toward a world of potential harms. AI does not act on its own, but these models have the capacity to supercharge human flaws and empower malicious actors at new scales.

Some of these harms are still revealing themselves. Large language models (LLMs) have emergent behaviors. These are capabilities learned through training and not revealed in testing — which developers may not even be aware of — that express themselves in worrisome ways, such as the ability for AI models to find cybersecurity vulnerabilities or even design chemical weapons. Based on the current trajectory, the capabilities of these systems will continue to evolve more quickly than top experts can track and current research and oversight institutions can anticipate.

But many of the potential challenges posed by generative AI have already become all too common over the last decade: conspiracies gone mainstream, inappropriate content being directed at children, election manipulation, fraud and deception schemes, the worsening mental health crisis, and more. We have seen these challenges raised in connection to social media, another technology that was rushed to the public in a similar arms race. But as OpenAI CEO Sam Altman himself testified, these challenges are going to be “on steroids” with AI.

Many of the same Big Tech firms behind the social media revolution are at the forefront of the new wave of AI. The breakthroughs in generative AI that we’re seeing today have been made possible by the past decade’s dramatic expansion of both tech infrastructure and available training data, both of which have links to today’s tech giants. Powering these AI models requires massive processing power, often overlooked manpower, and the ability to afford long R&D timelines, which necessitates the kind of upfront investment that only major firms can allocate.

Honing these models also requires a massive amount of data on which LLMs can be trained in order to respond appropriately to a user’s query. In order to satisfy this demand, AI developers trained their models with endless amounts of information pulled from across the internet, including search engines, online blogs, and especially social media platforms, where users self-populated platforms and generated massive troves of content. This is why we’ve seen the development of these technologies concentrated in the hands of only a few powerful companies, contrary to the decentralized goals of Web 3.0.

Generative AI Compounds and Expands Social Media’s Harms

Generative AI and social media are inextricably linked in their origins, design, and operations, and now they’re being deployed together in a way that has the potential to supercharge these threats. Snapchat recently launched “My AI,” a new AI chatbot based on ChatGPT that sits at the top of every Snapchat+ user's list of “friends.” Within days of the launch, “My AI” was giving dangerous advice to young teens. Meta and YouTube also plan to integrate generative AI into their platforms to enhance creative tools, a decision that may make the proliferation of disinformation easier.

But even if social media companies decided not to directly integrate generative AI into their products, systems like ChatGPT and Midjourney are already making social media’s content moderation whack-a-mole approach that much more difficult with synthetically generated content that’s quick to go viral and difficult to authenticate. Recent AI-generated images of former President Trump being arrested and an advertisement created by the RNC are only the beginning.

Lastly, as generative AI continues to become intertwined with work, education, finance, and politics, it has the ability to exacerbate issues of inequality, discrimination, privacy, harassment, and more. Open-source and leaked models will likely compound these problems by empowering dangerous actors with powerful tools, making them that much more difficult to address.

Building on the Framework and Lessons of Regulating Social Media

Congress is already considering a number of bipartisan proposals that could help reign in generative AI, particularly when it is embedded into social media: comprehensive privacy protections, mandatory transparency, and researcher access frameworks, kids’ safety protections, algorithmic impact assessments, and antitrust reform. An exhaustive list of the legislative proposals before Congress that would impact the use or development of generative AI is here. Many of these proposals can be strengthened and clarified to apply to generative AI systems.

At the same time, however, AI will inevitably require new regulatory and oversight approaches to grapple with growing challenges like AI-enabled identity theft and cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Here, policymakers can build off of key principles learned from the push to bring regulation and oversight to social media.

Principle 1 — Focus on Design:First, addressing the root causes of harm by focusing on the design and development of products is more effective than focusing on outcomes or content. To date, the most impactful social media bills are content-neutral and design-focused. The California Age Appropriate Design Code and the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) take a safety and privacy by default approach, mitigating harms before they occur by compelling platforms to create products more aligned with kids’ needs. The principle of designing products safely from the outset should be applied to AI, both for standalone products and those utilized by social media companies.

Principle 2 — Balance Information Asymmetries: We need to be able to look under the hood of these powerful technologies. Transparency and accountability mechanisms are critical for enhancing public understanding, empowering users, and informing evidence-based policy. The Platform Accountability and Transparency Act (PATA) — a bipartisan bill led by Senators Chris Coons (D-CT) and Bill Cassidy (R-LA) — would open the black box of social media platforms so that independent, vetted researchers, civil society groups, and regulators can have insight into these platforms' impacts on society. A similar approach that provides key stakeholders insight into models’ training data, as well as the ability to conduct unstructured research and testing on these models, could help protect against potential harms and ensure that AI systems are built safely.

Principle 3 — Address the Business Model: Finally, shifting the incentives of technology companies is necessary to ensure that products are developed with consumers’ best interests as a priority, not just the pursuit of profits. Both KOSA and the CA Age Appropriate Design Code establish a duty of care, which is similar to a fiduciary standard, for social media platforms to prevent and mitigate harm to minors. And the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) directly tackles the underlying social media business model — which relies on the pervasive extraction and manipulation of user data — by minimizing both the types of data that platforms can use and the purposes for which it can be used. These types of frameworks can shift the incentives and business practices of AI companies by extending their responsibilities to a larger set of stakeholders, not just to shareholders.

Moving Forward

Leading policymakers, technologists, and stakeholder groups are rightfully sounding the alarm on generative AI. The Senate’s AI hearing offered a reason for optimism, with members coalescing around AI regulatory solutions such as transparency and accountability mechanisms (e.g., scorecards and researcher access), privacy-preserving practices, updated liability frameworks, and licensing.

But as we saw with social media, public support for regulation often fails to translate into action or meaningful policy. With history beginning to repeat itself — the same players following similar profit-maximizing incentives and exploiting slow-moving regulatory regimes — we hope that lessons from the past can inform our present. Sensible safeguards and accountability are how we lead with an affirmative and innovative vision of technology that serves our communities and upholds our democracy.

Authors