TikTok’s Confidence-Destroying Bold Glamour Filter is the Logical Product of Platforms Built for Consumerism

Rachel Griffin / Mar 24, 2023Rachel Griffin is a PhD candidate and lecturer at the Law School of Sciences Po Paris. Her research focuses on European social media regulation and its implications for structural social inequalities.

A very conventionally attractive curly-haired woman sits on her bed, looking down into a propped-up phone camera. ‘My confidence is about to go way down,’ she says, then the video changes abruptly: she is still very conventionally attractive, but not wearing any makeup. She flinches, looking disgusted.

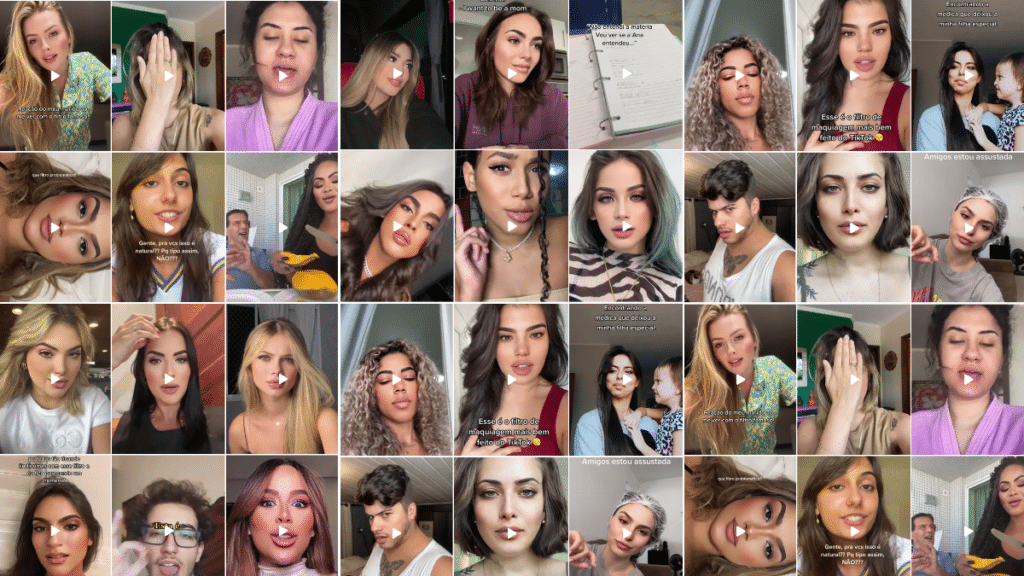

This is just one of a recent flood of videos trying out TikTok’s new Bold Glamour ‘beauty filter,’ which seamlessly edits videos in real time to resculpt users’ faces and add a full face of makeup. Several such examples were collected on Twitter by Memo Akten, a professor of computational art and design at UC San Diego. Like many TikTok trends, the beauty filter was quickly picked up by mainstream media. A consensus quickly formed that showing users dramatically better-looking, uncannily realistic versions of themselves and others is going to harm people’s wellbeing and mental health. Akten went so far as to describe it as ‘psychological warfare & pure evil.’

That may seem dramatic, but there is plenty of evidence providing reasons for concern about the social and psychological effects of ‘beauty filters’, which are a widespread and popular feature on major platforms like Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok (Bold Glamour has drawn attention for its technical sophistication and realism more than its style.)

I think people are right to push back against unrealistic and exclusionary beauty standards, and to criticize TikTok for designing products that are likely to harm users’ mental health. But as the latest social media trend bubbles up and dies away, we might lose sight of the broader context. Today’s dominant social media platforms are spaces for advertising and, increasingly, e-commerce – and promoting stereotypical and unattainable ideals of beauty has historically been good for business. For as long as that’s the case, social media companies will keep designing features that make people feel bad about themselves, long after the media cycle has moved on.

Facial filters, beauty standards and body image

Experts and policymakers have frequently raised concerns about the impact of social media use on young people’s mental health, body image and self-esteem. This even came up briefly in this week’s Congressional hearing on TikTok, which otherwise mainly focused on national security and privacy, with Representative Kathy Castor (D-FL) claiming that social media use is linked to "body dissatisfaction, disordered eating habits, anxiety, depression, self-injury, suicide ideation, and cyberbullying" and that "TikTok could be designed to minimize the harm to kids, but a decision was made to aggressively addict kids in the name of profits."

While such discussions often tend towards alarmism, exaggeration and ‘moral panics’, as psychologist Amy Orben has shown, there is psychological research supporting some of the underlying claims. Social media use is generally associated with worsened body image and intensified comparison of one’s own appearance to others – especially for women, and especially when the focus is on sharing and engaging with visual images. For many young people, social pressure to post images which gain a positive reaction from others encourages intense self-scrutiny and pressure to conform to dominant beauty standards, which are not only unattainable for many, but highly gendered and racialized.

Filters exacerbate these dynamics by providing even more unrealistic standards for comparison, and raising the standards about what looks ‘good enough’ to share. They transform users’ faces to fit idealized beauty standards, effectively showing them what they are ‘supposed’ to look like. Even those that aren’t described in terms of ‘beauty’ or ‘enhancement’ – like the novelty animal faces that first became popular on Snapchat and Instagram – tend to resculpt users’ faces in the same predictable ways: bigger eyes, smaller noses, smoother skin. In interviews with MIT Technology Review journalist Tate Ryan-Mosley, young women openly state that they use filters to look better: “The beauty filter sort of changes certain things about your appearance and can fix certain parts of you.”

In videos testing Bold Glamour, users say that the contrast between their real and enhanced faces makes them feel bad, and often express concern that younger women will think looking like this is normal or expected. The idea that filters can tangibly affect people’s body image and self-esteem is not just speculative: one study found that ‘the use of face-altering software on social media has a significant association with subsequent desire to undergo facial cosmetic procedures.’

These effects are likely to fall particularly hard on people of color and others who are already excluded by the beauty standards that predominate in Western media. Journalists have pointed out that if the filters work on people of color at all, they reinforce social hierarchies in which typically white features like pale skin and small noses are equated with beauty – and people who lack those features are deemed unattractive.

Another aspect that has attracted less discussion is the crude gender essentialism of these apps. Apparently, when TikTok users whose faces are read as masculine apply the Bold Glamour filter, it produces a different version with no makeup and more stereotypically masculine features. Presumably, TikTok chooses which version of the filter to apply by automatically categorizing users as male or female. Its privacy policy states that it uses user data to infer attributes like age and gender, and its US (though not EU) version permits the collection of biometric information.

There are widely-available tools to predict gender based on facial features – albeit relying on models of gender as a fixed, binary physiological trait which are scientifically invalid, and profoundly harmful to trans and non-binary people. TikTok’s makeup-free ‘male’ and hyper feminine ‘female’ versions of Bold Glamour might be a particularly inane example, but binary gender models are ubiquitous in other platforms’ filters, and in facial recognition technologies and user profiling systems more generally. In the case of beauty filters, these rigid gender categories erase and exclude trans, non-binary and queer people, but they also reinforce reductive stereotypes – like makeup being only for women – that are degrading to everyone.

Impossible beauty standards are good for business

In light of all these issues, it’s good that TikTok users are taking a critical attitude towards filters, and that journalists are calling the company out for introducing features that could be harmful. However, just criticizing TikTok as irresponsible or calling for it to add labels to videos where a filter is used – essentially suggesting that properly-informed users should be capable of resisting the unattainable beauty ideals they’re bombarded with – misses the bigger picture.

For one thing, the controversy around Bold Glamour is in many ways good for TikTok (and I’m guessing the company expected exactly this response when it deployed the filter). Whether users are marveling at the filter’s realism or performing horror, they’re jumping on the latest viral trend, creating more TikTok content and keeping the conversation going. Even the mini-backlash against Bold Glamour is creating engagement, clicks and ad revenue – and putting TikTok at the center of media attention. Amid a wave of excitement around the new generative AI tools being deployed by OpenAI, Microsoft and Google, TikTok has successfully drawn attention to its own generative AI capabilities, ensuring it’s still seen as at the technological cutting edge.

More fundamentally, discussing TikTok’s deployment of Bold Glamour as thoughtless or ‘pure evil’ obscures the good reasons that it and other companies continue building platforms that make people feel bad about themselves. Princeton University computer scientist Arvind Narayanan argues that recommendation algorithms tuned to maximize user engagement will often cater to peoples’ immediate impulses rather than their considered opinions – and no matter how critical we are, impossibly good-looking filtered faces will tend to grab most people’s attention. In Akten’s video compilation, users expressing exaggerated horror at the filter’s effects on their self-esteem still stare into the camera, showing off how ‘fucking gorgeous’ they look. As Vox’s online culture commentator Rebecca Jennings points out, for better or worse, people like looking at attractive women, and like older media, social media have always taken advantage of this to keep users engaged.

Importantly, advertising-funded platforms are not just designed to package users’ attention and sell it to advertisers, but to put users in a ‘buying mood’ that will maximize the value of that attention – for example, by promoting pro-consumerist, gender-stereotypical content that aligns with advertisers’ preferred audience segments, as Sheffield University researcher Sophie Bishop has shown. Advertisers and marketers have always exploited and promoted unattainable beauty standards to sell cosmetic, ‘wellness’ and fashion products, and this has always shaped media content beyond the adverts themselves. For example, Gloria Steinem has written about how her feminist magazine Ms. struggled to attract advertising revenue because it refused to follow the industry norm of providing superficial, pro-consumerist ‘complementary copy’ to beauty adverts.

As well as advertising, TikTok’s business model relies heavily on e-commerce, promising its marketing customers an ‘infinite loop of shoppertainment’ where users’ desire for ‘simple and immediate gratification’ makes it easy to promote impulsive purchases. Surrounding users with images of beautiful, heavily made-up, hyper feminine women and showing them how much better they could look with a few tweaks is a good way to get them to impulse-buy makeup, skincare and other products that promise to assuage their insecurities.

Tellingly, alongside the trend for videos criticizing Bold Glamour, TikTok influencers have been promoting ‘recreate the Bold Glamour look’ makeup tutorials – perfect ‘complementary copy’ for makeup brands. In parallel, skincare brand Dove – famous for adverts emphasizing ‘real beauty’, styled as public-interest campaigns driven by ostentatious concern for women’s self-esteem – is now promoting its products with a ‘#TurnYourBack on Bold Glamour’ TikTok campaign. People angered by unattainable beauty ideals can also be converted into a profitable market segment.

For as long as social media are built for marketing and e-commerce, they will promote exclusionary beauty standards, reductive gender stereotypes and shallow, consumerist attitudes. TikTok is currently in the spotlight following the Congressional hearings, but as many commentators have pointed out with respect to privacy and security, this shouldn’t distract attention from the underlying structural dynamics of the social media industry. The same goes for platforms’ effects on mental health. Recommendation algorithms, filters and other features that shape user interactions have always been designed to suit the needs of platforms’ advertising clients, and this is unlikely to change without fundamental changes in platforms’ business models and governance structures. With the rising availability of generative AI and the prospect of ‘semiautomated social media’, the most likely future trend is that ever more of what we see online will be fine-tuned to suit brands and put us in the mood to shop.

Authors