The U.S. Needs Controls on Data Brokerage

Justin Sherman / Jun 24, 2022Justin Sherman is a senior fellow at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy and runs its data brokerage research project.

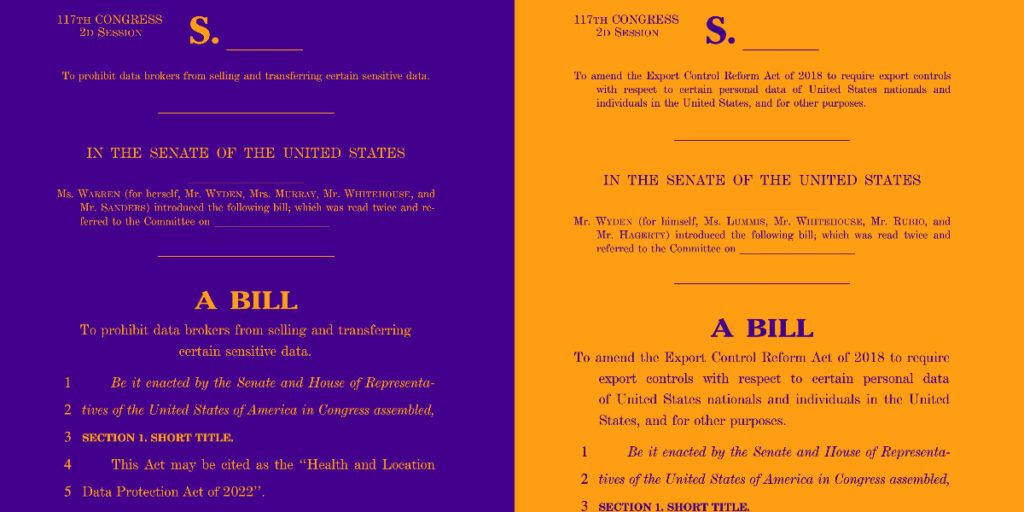

Last week, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA)—along with Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR), Patty Murray (D-WA), Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), and Bernie Sanders (I-VT)—introduced the Health and Location Data Protection Act, which would prohibit data brokers from selling Americans’ health and location data. This week, Senator Wyden introduced another bill—The Protecting Americans’ Data from Foreign Surveillance Act—along with Senators Whitehouse, Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), Marco Rubio (R-FL), and Bill Hagerty (R-TN) to control the sharing and transfer of certain sensitive categories of US citizen data to foreign entities deemed a national security risk.

Both bills take aim at the sprawling data brokerage ecosystem, wherein US companies collect, aggregate, analyze, package, and make available data on millions of Americans. The harms inflicted by this ecosystem on civil rights, consumer privacy, physical safety, and national security—not to mention the harms inflicted on specific communities ranging from heavily policed Black and brown communities, to the poor, to the elderly, to survivors of domestic violence, to veterans with PTSD—demand immediate regulation. While Congress must pass a comprehensive consumer privacy law, there is no reason that legislators should allow the current harms of data brokerage to continue in the meantime.

Many existing privacy laws do not cover data brokerage. For example, the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act, otherwise known as HIPAA, narrowly introduces privacy and security controls on covered health entities, like your doctor. It does not cover period tracking apps, virtual therapy apps, data brokers, and many other kinds of companies, which means they are entirely within their rights to sell your health data like prescription lists, surgical histories, and much more.

The harms are numerous. Health insurance companies, among others, have leveraged data brokers to buy up data on hundreds of millions of Americans—including data concerning race, education level, marital status, net worth, and online purchases. Consumers often have no idea this is happening. They also typically have no recourse, because even in the few states, like California, where consumers can submit do-not-sell-my-data requests to companies, data brokers may be unresponsive; a 2021 Consumer Reports study in California found that data brokers had even set up illegally onerous opt-out processes.

Take law enforcement as another example. Currently, law enforcement agencies are allowed to purchase data from companies to spy on Americans without warrants, disclosure, or robust oversight. This is because existing laws, akin to HIPAA and health data, do not adequately cover data brokerage in a law enforcement context. As the nonprofit Center for Democracy & Technology wrote in its December 2021 report on the issue, “the Electronic Communications Privacy Act effectively contains a loophole allowing law enforcement to acquire communications data commercially from data brokers and evade otherwise applicable requirements that they must use legal process to obtain data directly from service providers.” Many law enforcement agencies purchase data in this way, from the Federal Bureau of Investigation to Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The data brokerage ecosystem in turn enables law enforcement to increase its surveillance of US citizens, to do so without oversight and controls, and to further already racist and otherwise discriminatory policing practices. For example, the fact that data broker (or “analytics company”) Mobilewalla was legally allowed to secretly surveil participants in Black Lives Matter protests in Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and New York in 2020—and then use that information to profile those individuals—underscores the dangers of data brokerage when data is collected and aggregated on marginalized individuals, or on individuals participating in legal activities that law enforcement dislikes.

Congress should not wait for a comprehensive privacy law to pass these two bills. Health and location data are incredibly sensitive and can be used for a range of harms, from profiling and exploiting consumers to spying on citizens without warrants to carrying out stalking and violence. Imposing strong legal and regulatory controls on this dangerous practice is vital to protecting the privacy of every American—particularly women, the LGBTQIA+ community, people of color, the poor, and other vulnerable communities.

In similar form, right now, it is far too easy for foreign governments to purchase sensitive data on the demographic information, political preferences, internet search histories, mental health conditions, and GPS movements of American citizens, politicians, judges, government officials, and even intelligence officers and members of the military—all without running into any substantive controls. This information could be used for profiling, blackmail, intelligence operations, the design and execution of online disinformation campaigns, and much more.

Data brokerage poses risks to individuals and to society as a whole across civil rights, consumer privacy, physical safety, and national security, and Congress should act now.

Authors