The Tech Money Machine: How Silicon Valley Buys Power — and Shapes Reality

Alix Fraser, Michael Beckel , Liana Keesing, Amelia (Mia) Minkin, Isabel Sunderland / May 22, 2025This post is part of a series of contributor perspectives and analyses called "The Coming Age of Tech Trillionaires and the Challenge to Democracy." Learn more about the call for contributions here, and read other pieces in the series as they are published here.

In July 2024, the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) passed the Senate with a staggering 91–3 bipartisan vote. Nearly 9 in 10 Americans backed the bill. Parents, teens, and more than 200 advocacy organizations rallied behind it to hold tech companies accountable for the harms their products inflict on children. And yet, when it reached the House, the bill died.

Why? Because even in the face of emotional pleas and overwhelming public consensus, tech money spoke louder.

Meta (the parent company of Facebook and Instagram) and other tech giants deployed an aggressive, behind-the-scenes campaign to block the bill. They leveraged financial muscle, flooding Congress with lobbyists and bankrolling civil society groups that looked independent but were in their pocket and ready to do their bidding. Then, in the final weeks of the 118th Congress, after securing 30 years’ worth of state and local sales tax exemptions and local property tax abatements, Meta announced a $10 billion data center in Louisiana — home to the two House leaders who controlled the bill’s fate. It was a flex of economic power dressed as civic investment. Despite its popularity, the bill never even received a vote on the full House floor.

What happened to KOSA isn’t an isolated case. It is part of a toxic, familiar cycle: profits fuel political power, and that power blocks reforms meant to protect the public. We’ve seen this before — from Big Oil’s denial of climate change to Big Pharma’s resistance to opioid regulation. But Big Tech is uniquely dangerous. Its power is not limited to wealth or lobbying; it controls the spaces where much of the public debate occurs, and as such, it plays a big role in how our democracy works or, increasingly, does not work. That control amplifies its influence and accelerates the cycle to even more dangerous extremes.

Unmatched lobbying power, unchecked influence

Few industries have amassed power as quickly or as thoroughly as Big Tech. Apple, Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft dominate not just the digital economy but the economy, period. With hundreds of billions in annual revenue, they can shape markets, steer policy, and influence public opinion to suit their interests.

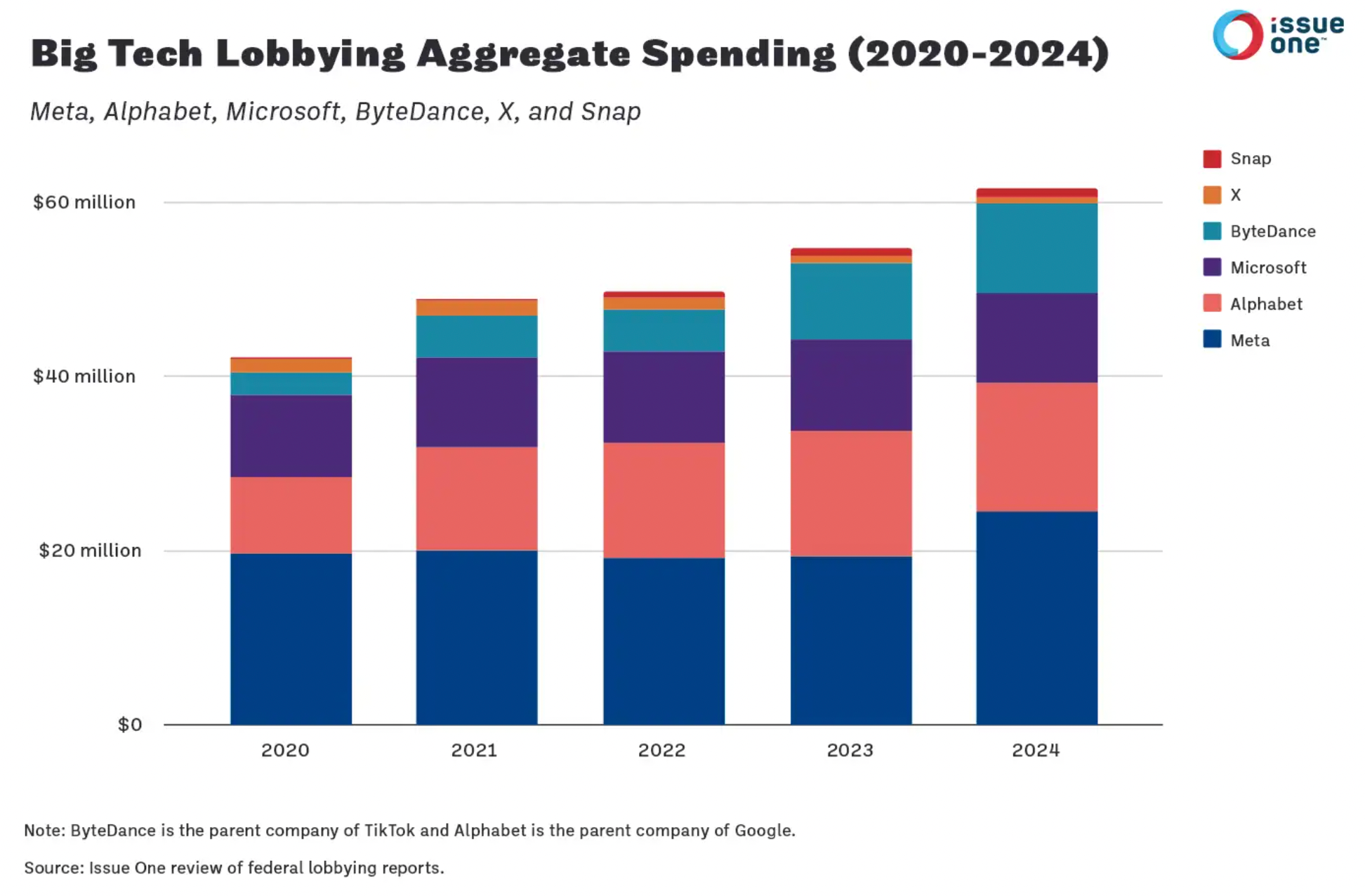

Their economic might fuels a sprawling political machine. According to an Issue One analysis of data from OpenSecrets and disclosures filed with Congress, from 2020 through 2024, major tech firms, including Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, ByteDance, X, and Snap, spent a staggering $260 million — more than a quarter of a billion dollars — on federal lobbying. These companies have employed nearly 500 lobbyists over three different Congresses — one for every two members of Congress — to shape policy behind closed doors. Their spending only keeps climbing. In 2024 alone, these tech titans spent $61.5 million lobbying Congress, a 13% increase from the previous year and 46% more than in 2020. Early 2025 figures suggest that the number will rise again.

At Issue One, we have seen the pattern firsthand: When meaningful oversight gains momentum, the money surges. Whether the target is antitrust enforcement, data privacy protections, or online safety legislation like KOSA, tech companies mobilize quickly to dilute, delay, or derail reform. Lobbying is not just brand management — it is their core strategy for preserving profits and avoiding accountability.

This is not confined to Washington. It is also playing out in state capitals across the country.

Consider the fight over privacy. Since California enacted a landmark privacy statute in 2018, Big Tech has aggressively worked to undercut similar efforts elsewhere. In Washington state, Amazon and its allies helped transform a failed 2019 bill into a blueprint for weaker legislation, starting with Virginia’s 2021 law, which was literally handed to a lawmaker by an Amazon lobbyist. That bill became the industry template. Of the 19 states that have passed comprehensive privacy laws, most follow the Virginia model: laws that promise protection but lack meaningful enforcement.

And the scale of the opposition is staggering. The Markup found 445 lobbyists and firms representing Big Tech in the 31 states that debated privacy bills in 2021 and 2022. Unlike at the federal level, where members of Congress often have a dedicated technology policy staffer to help them understand these issues, state legislators often only have one or two staffers in total; as such, they are much more dependent on lobbyists for even basic information. Generally speaking, the smaller the state, the easier it is for industry lobbyists to come in and shape the contours of the debate, especially when it comes to more technical policy topics like data privacy. Because many state lobbying records are opaque and lacking in key details, and tech companies often work through groups like TechNet and the State Privacy and Security Coalition, the 445 number is almost certainly a lowball estimate.

The pattern is unmistakable: Whenever regulation threatens to restrict data harvesting, curb user manipulation, or shift liability onto the companies, Big Tech shows up in force. More often than not, they succeed. The result is a patchwork of weak rules, missed opportunities, and a regulatory environment designed around corporate convenience, not public protection. It is a self-reinforcing cycle: Money buys influence, influence blocks reform, and the absence of reform leads to even more profit, which can be used to buy even more influence.

Controlling the narrative — and the debate

What sets Big Tech apart from other corporate giants is not just its money or scale. It is that these companies control the spaces where public discourse unfolds. They dictate what information we see, what goes viral, and whose voices are amplified or buried. They do not just influence the debate — they are its architects.

After Congress passed legislation requiring ByteDance (the parent company of TikTok) to divest TikTok’s US operations, the company retaliated by pushing in-app alerts to its 170 million American users, urging them to contact their lawmakers. Some offices received 20 calls a minute. TikTok followed with a coordinated PR blitz, casting itself as a defender of small businesses and free speech. That messaging did not stay on just TikTok — it spread across Meta-owned companies and even wraparound print ads in legacy outlets like the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

When a company can simultaneously mobilize millions of users and dominate the media narrative, it becomes nearly impossible to distinguish corporate speech from democratic discourse.

This is more than savvy marketing. It is meta-political power: the ability to shape public perception about the very laws intended to rein tech in.

Despite their lofty proclamations about safety and neutrality, it is important to remember that these tech companies treat moderation of their products as nothing more than a political bargaining chip. Before the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol, Facebook hosted more than 650,000 posts questioning the 2020 election. After the violence, social media companies pledged to prioritize integrity. But by 2024, many had dismantled the very safeguards they once touted, including trust and safety teams and content moderation policies. These were not decisions about free speech — they were strategic calculations. Moderation is deployed when under scrutiny and abandoned when rollback earns political favor. If tech companies are willing to tilt the scales of discourse to appease those in power, there is little reason to doubt they would manipulate political debate to serve their interests.

Reclaiming the digital public square

Big Tech’s unchecked control over policymaking and the digital public square makes its influence unlike anything we have seen before. These companies are not just distorting markets — they are rewriting the terms of public debate. And yet, the mechanisms to hold them accountable remain dangerously outdated.

It does not have to stay that way. With the right reforms, it is possible to chip away at the machinery that lets private social media companies rewrite public rules.

The first step is long overdue: campaign finance and ethics reform. As long as tech giants can pour millions into elections and policymaking, often in the dark, no regulation is safe from sabotage. Reforms like the Honest Ads Act, which would require disclosures for online political advertising, and bans on corporate donations to super PACs could start to level the playing field. Some states are already moving — in November, Maine voters approved limits on super PAC contributions. Without guardrails like these, the public cannot see who is spending money to shape policy or why.

Second, we need to close the revolving door between Big Tech and government. Social media and AI companies fund fellowship programs that often embed former — or future — employees inside Congress, shaping how lawmakers understand complex tech issues that directly affect those companies’ profits. While these fellows help fill a critical expertise gap, there is a better model: restoring and modernizing the Office of Technology Assessment, an independent body that once provided Congress with nonpartisan science and technology advice without industry influence. To rebuild public trust, we need stronger conflict-of-interest rules and independent pathways for policy expertise that do not rely on corporate boardrooms.

Third, transparency into social media companies’ algorithms is no longer optional. These systems shape what people see, believe, and act on — but attempts to study them are often blocked or punished. Independent researchers have been denied access, sued, or harassed out of the field entirely. Congress can reverse that by passing legislation like the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act (PATA), which would grant researchers protected access to the data needed to understand and expose how these systems work.

Fourth, we need a dedicated federal agency to oversee the digital marketplace. Every major industrial era — from food and drugs to finance and broadcasting — has eventually triggered the creation of regulatory bodies. Today’s internet, with its unprecedented scale and speed, has outgrown the capacity of our current institutions. A digital regulatory agency could monitor emerging harms, enforce basic standards, and bring in independent technical expertise to regulate at a much faster pace than Congress. We recognize the risks, including the threat of regulatory capture, and we know this idea is not politically viable yet. But over the long term, it is a necessary step toward building a regulatory framework capable of matching Big Tech’s power with meaningful oversight.

These changes won’t undo the past two decades of capture overnight. But they are foundational to creating the conditions for further reform. Without fixing how tech money moves through our system, progress on core issues like privacy, content moderation, kids’ online safety, and accountability will remain stalled.

There is a catch, of course: Big Tech’s influence is the very reason these reforms are so hard to pass. It is a self-reinforcing cycle, and that’s exactly why tech accountability advocates have to fight on two fronts. One is the battle to clean up the information ecosystem that tech companies have polluted for profit. But just as important is the fight to dismantle the political machinery that allows them to operate without consequence.

This is not just a fight over tech policy — it is a fight over who governs in a democracy: the people, or the Big Tech companies. If we want technology to serve the public rather than exploit it, the time to act is now.

Authors