The Supreme Court Can Help Fix Social Media Governance With NetChoice Ruling

Richard Reisman / Feb 9, 2024

The interior of the United States Supreme Court. Shutterstock

On February 26, the Supreme Court is to hear oral argument in the NetChoice cases, which concern the efforts of a trade association of technology firms to overturn recently passed laws in Texas and Florida that put restrictions on how platforms moderate content. Those laws are viewed by many experts as unconstitutional because they would improperly compel social media platforms to either carry or not carry certain kinds of otherwise legal user content. Amicus briefs filed late last year suggest the Court should have an easy basis to invalidate these laws based on First Amendment precedent, since they infringe on the rights of the platforms to exercise judgment over what speech they choose to host or not.

Of the dozens of amicus (friend of the court) briefs filed with the Court in support of NetChoice, one stands out. The eminent political scientist, Francis Fukuyama, was supported by technology law experts Daphne Keller, Jack Balkin, Margaret O’Grady, Seth Greenstein, and Robert Schwartz in submitting a brief that goes beyond simply arguing why the Florida and Texas laws are unconstitutional. It sheds new light on how legislators can limit the harms of current approaches to managing social media in a way that does not infringe on the rights of “platforms-as-editors” – or, importantly, on other parties’ First Amendment rights.

In so doing, the Fukuyama brief points to the possibility that social media content moderation and recommendation services could be managed differently, and in such a way as to better mitigate the concerns the Florida and Texas laws seek to address. It explains how the Court can overturn the two laws in a way that does not just kick the can of social media governance down a dead-end road – leading to much more wasted time and effort – but instead, could show legislators and others a way past current dilemmas. That would not only help limit harmful extremes in social media -- it would also protect both user freedom of expression, and the often neglected freedom of impression: who we associate with and listen to.

The core idea is enabled by an alternative technical approach to managing online speech. The authors of the brief argue that instead of trying to institute laws that purport to mandate that platforms, themselves, protect the diversity of speech on the internet – which could likely backfire, causing platforms to remove too much content or, conversely, to force-feed users unwanted content – the Court should use this opportunity to encourage a more elegant solution that would not require an “unprecedented expansion of government power over free expression online.” The solution, they say, is for more user control to be baked into the service architecture of social media.

User controls, on the other hand, allow people to choose the kind of content moderation and recommendation systems they prefer, and make their own decisions about the curation of their social media experience. User controls put power over each individual’s experience on social media in the hands of the people, rather than the State. Technology including middleware and interoperability can unlock a competitive ecosystem of diverse content moderation providers, letting users decide on their own preferred rules for online speech without forfeiting the networks and connections enabled by large platforms today. State action to encourage or unleash the development of more and better user controls would advance the States’ goals by far less restrictive means than Texas and Florida propose.

The Court, they say, should consider the potential of a fundamentally more interoperable internet that allows each user to make their own choices about online speech – by delegating control of what they see on social media to independent attention agent services that sit between them and the platforms. A freely chosen set of those services can work as an agent faithful to each user to decide what should go into their feeds. That would change the game from concentrated control by platforms, seen by many as undemocratic and exploitative “platform law,” and negate the impermissible alternative of government control. Instead, it returns to individuals their traditional freedom to make their own choices over what kind of content they receive – who and what they listen to.

This middleware choice strategy has its roots in the original design of the internet as an open network – and this strategy has long been implicit in traditional society. Its relevance to social media governance had been percolating in technical and legal circles for some years (including by Keller, Mike Masnick, and me), but was so named and brought to wide attention by a team led by Fukuyama at Stanford in 2020-21.

Keller tweeted this summary after the filing of the Fukuyama brief: "These tools for user control over online content are, in First Amendment Terms, ‘less restrictive means’ to promote…anti-censorship goals. Because they exist, resorting to top-down, state-imposed speech rules cannot be justified." (She also provided extensive background in a January blog post.)

The brief quotes a Court precedent (Ashcroft, 2004) for restricting material harmful to minors based on user controls that can allow for “selective restrictions of speech at the receiving end, not universal restrictions at the source,” arguing that is “less restrictive means to achieve legislators’ goals.” It also suggests middleware services and interoperability as means for user choice, thus avoiding “universal restrictions at the source.”

By centering its arguments on this well-established principle of preference, where possible, for “less restrictive means” for regulating speech – in this case user choice, as may be implemented via agent middleware services -- the court might end infeasible legislative efforts that just waste time and effort trying to thread an eyeless needle of content-based mandates that serve as universal restrictions at the source. User choice of what to listen to is how societies have managed speech for centuries, and it is how the internet was intended to work. We should seek to facilitate that, not abandon it.

The Fukuyama brief also cites the Playboy decision (2000): “The core First Amendment principle at issue in this case is well-established: ‘Technology expands the capacity to choose; and it denies the potential of this revolution if we assume the Government is best positioned to make these choices for us’” and “The States’ free-expression goals can be far better advanced by putting control in the hands of individual Internet users.”

Reinforcing that: “The Court’s decision in Ashcroft affirmed the constitutional preference for user-controlled Internet filtering software over direct governmental regulation.” The brief concludes that “This Court has been rightly skeptical of laws that take away individual speakers’ and listeners’ ‘capacity to choose,’ and instead assume that ‘the Government is best positioned to make these choices for us.’ Playboy … The Florida and Texas laws show the folly of that assumption.”

I note that this is also established by an often-forgotten preamble in the much-discussed Section 230 of the Communications Act (1996): “It is the policy of the United States… to encourage the development of technologies which maximize user control over what information is received by individuals… who use the Internet…” Middleware agent services are just such a technology. Also, consider the larger normative question: When platforms grow to connect billions of people, why should they have exclusive “editorial” rights over who can say what to whom? And who listens to whom?

A number of the other amici in the Netchoice cases that focus on speech rights of platforms-as-editors also make arguments supportive of listener rights, notably those of Bluesky, Riley, and Copia, and of Public Knowledge. One amicus on behalf of a group of twenty Law Scholars focuses on the argument that “users have a First Amendment right to choose the speech they listen to.”

Implementation of middleware services is still in early stages, but notable examples include the Block Party service that served Twitter users until Musk cut it off, and the BlueSky service that is becoming increasingly popular and features an expanded vision of “algorithmic choice.” That is just the start of the types of services and platforms that middleware can enable. Hopefully both upstarts and incumbent firms can be encouraged to see the wisdom of voluntarily giving users this kind of choice. But to the extent it may be needed, efforts to legislate rights of users to delegate to such middleware agents are being formalized in the pending Senate ACCESS Act, and the European Union’s recently enacted Digital Markets Act, and even more directly in NY State Senate bill S6686.

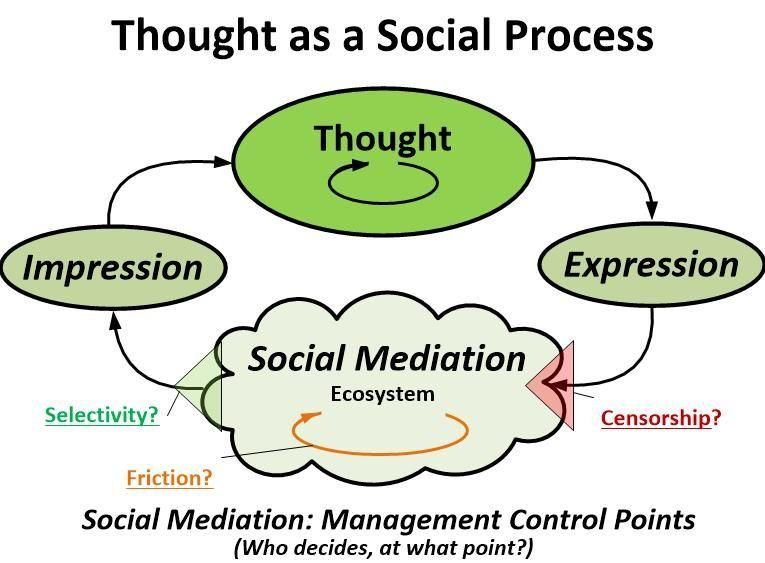

Consider the fundamentals of the underlying social process: Thought => Expression => Social Mediation => Impression, and more thought. With a robust, largely bottom-up Social Mediation Ecosystem (possibly with limited top-down elements) and user freedom of impression, we do not need to censor expression. As a normative principle, that should remain as open as possible. Protecting freedom of impression will let users, and the agent services that mediate on their behalf, limit the reach of harmful speech.

R. Reisman

Broadening this beyond the argument in the Fukuyama brief, I recently suggested that user-chosen middleware can provide the technical foundation for three pillars that synergize to help shape our thought as an open social process – with little imposed censorship. That is not just 1) individual user agency, but also 2) a social mediation ecosystem (our web of communities and institutions), and 3) consideration of reputation (and identity) to give weight to both. We forget that over centuries society developed a robust and evolving social mediation ecosystem that gently guided our listening and restrained the excesses of free speech. We urgently need to revitalize that ecosystem.

To be clear, the solution posed by Fukuyama’s brief to the Court is not merely a matter of techno-solutionism – nor is it proposed as just one simple trick. The proposed solution is enabling – to simply break the pathology of tech that amplifies the information failure of modern society in coping with the compounding polycrisis – and instead, open that to new methods for healthy augmentation of human discourse. From a historical perspective, we are now only beginning to rebuild human society online. That will be a huge and continuing whole-of-society undertaking. But what this solution does is shift from counterproductive efforts to over-regulate speech and ignore the larger ecosystem, toward building a foundation for reviving the ecosystem for collectively generative and organic self-regulation of speech.

And even if the importance to a robust and agile society based on strong First Amendment rights is less categorically established elsewhere, where expression rights may be “balanced” in “proportionality” to other rights, success in the US in protecting freedom of impression through user agency might show the way for other countries to also apply “less restrictive means” to find a both/and solution that regulates online speech in a way that also protects those other rights.

So, back to the “techno-legal-solutionism” facing the Supreme Court: By emphasizing the need to consider this kind of “less restrictive means” in its upcoming NetChoice decisions, the Court might clearly point legislators and builders towards a path that can support all three vital pillars of human discourse that are now being fractured. That could, in time, create the foundation for rebuilding and augmenting them.

Authors