The Siren Song of “AI Safety”

Brian J. Chen / Nov 15, 2023Brian J. Chen is the Policy Director of Data & Society.

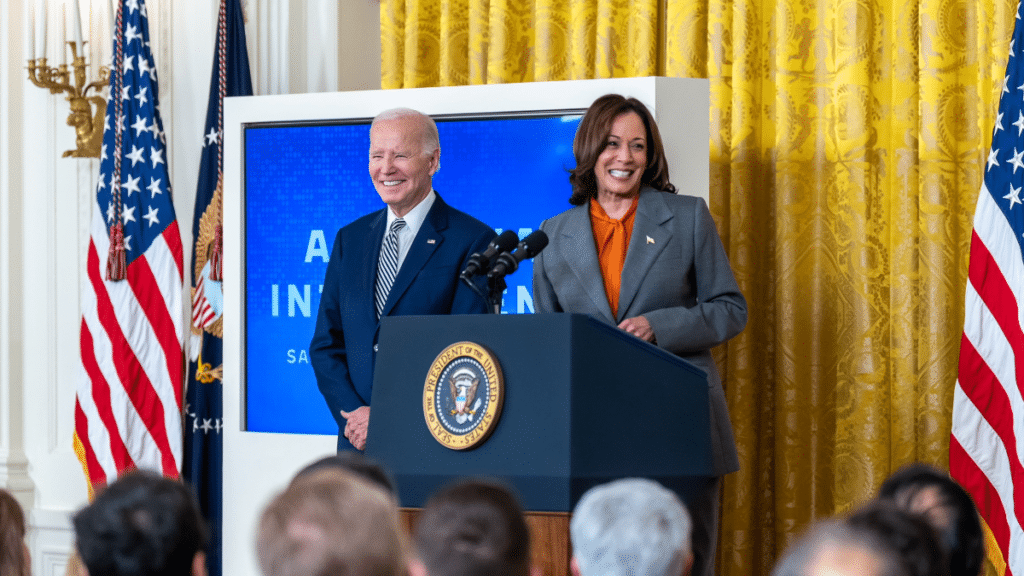

On November 1, delivering prepared remarks coinciding with the UK’s AI Safety Summit, US Vice President Kamala Harris offered a carefully-worded definition of “AI safety.” “We must consider and address the full spectrum of AI risk,” she said, “threats to humanity as a whole, as well as threats to individuals, communities, to our institutions, and to our most vulnerable populations.”

Even as many applauded the Vice President’s evocation of current harms, the speech firmly anchored policymaking to “safe AI.” Certainly, the maneuver is smart politics. But the now-ubiquitous call to “AI safety,” if history is any guide, may limit the spectrum of debate and reconfigure the solutions available to remediate algorithmic harms. US carceral scholarship, in particular, illustrates how calls to “safety” have flattened structural solutions into administrative projects.

Undoubtedly, “AI safety” is having a moment. Two weeks ago, the Biden administration announced its executive order on AI, entitled “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI.” Only a few days later, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the UK’s new AI Safety Institute. The US launched its own safety consortium that same day.

So, “safe AI” is popular. But what is it really? The authors of a forthcoming paper offer a provocation: what if “AI safety” is not a concept, but a community? By locating it as a cohort with specific interests and practices, the authors underscore how this well-funded, well-connected group increasingly sets the terms of popular debate.

This community, which might alternatively be described as the “existential risk” camp, warn about self-aware machines that might exterminate humanity. Critics have called out their sleight-of-hand, arguing the doomers are distracting the public from their own business stake in the widespread adoption of AI. As Ahmed, et al., identify, this camp also includes ideologues. True believers in effective altruism, they catastrophize the AI problem to the extent that only they, the self-styled “technological supermen,” can secure humanity’s future.

Set against this “existential risk” community are the advocates who focus on AI’s current harms in the real world. Calling attention to algorithmic systems in the here and now, they focus on issues like AI’s dehumanizing effects on workers, impact to the climate, and harms to people’s civil and human rights.

As Vice President Harris’s speech exemplified, politicians are eager to join the two sides. Governing means corralling interest groups by some conceptual thread, and on the surface, “safe AI” does the job. For example, President Biden’s executive order addresses, as many groups applauded, AI’s harms in areas like housing, work, and education; it also marries those elements with technical protocols to manage “frontier” AI models.

If folding these competing camps under “safe AI” is smart politics, it may narrow the aperture of solutions and miss problems of political economy. It risks entrenching AI policy in bureaucracy—standards here, reporting requirements there—and missing the institutional dynamics of endless surveillance and the decline of worker power that make AI profitable in the first place.

It wouldn’t be the first time that “safety” interrupted progressive aims. In The First Civil Right, political scientist Naomi Murakawa points out how the “the right to safety and security,” a Truman administration turn of phrase to advance racial equality under a law-and-order banner, ultimately limited structural change.

To advance policies to shield Black Americans from white mob violence, the Truman administration defined Americans’ “right to safety” as freedom from “lawless violence.” But, Murakawa argues, the creation of “lawless” violence legitimated “lawful” violence. As the bounds of social change constricted to whether violent acts satisfy procedural norms, the policy goals shifted from ending violence to modernizing police bureaucracy. We may celebrate that these acts were done in service of social equality—that didn’t stop them from ballooning America’s prisons and prefiguring the police surveillance state.

With little room to challenge state violence as a system of punishment, many reformers could only advocate for system fairness. As Murakawa notes, the horizon of many people’s activism was strictly to evaluate “the administrative quality by which each individual is searched, arrested, warehoused, or put to death.”

Today’s “safe AI” could likewise dislocate efforts to challenge AI’s structural harms. Unable to challenge AI as systems of data extraction and labor expropriation, activists may discover they hold only the administration of safety as their cudgel: enforcing a routine of technical auditing, evaluation, and risk mitigation.

Of course, AI should be safe. And countless people across civil society, ethics teams, academia, and government are making it safer, pioneering ways to strengthen privacy protections and minimize system bias.

All the same, those who care about AI’s real world harms should resist the broad political banner. Compromise and consensus are the game of politics; but the sensible call to “AI safety” risks building a techno-bureaucracy that supports, not calls into question, the logic of ceaseless data expropriation.

Authors