The Science of Social Media's Role in January 6

Dean Jackson, Justin Hendrix, Tim Bernard / Oct 29, 2024A version of this article was previously published as a component of a report about how social media facilitates political intimidation and violence produced by Paul Barrett at the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights.

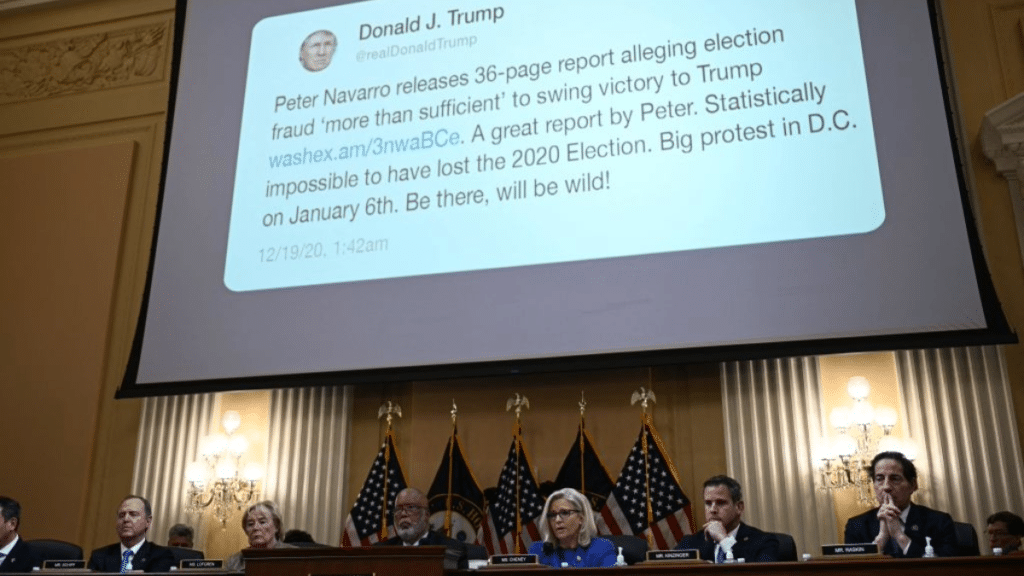

A tweet by former President Donald Trump appears on the screen during a House Select Committee hearing to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the US Capitol in the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on June 9, 2022. (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

These are the final days of the 2024 election, and the long shadow of the January 6th insurrection darkens them. Domestic partisans and foreign adversaries are already priming the public for false accusations of election fraud, and Americans fear that violence will mar the election process. Donald Trump—who has survived at least two assassination attempts thus far—has refused to rule it out if he does not win. And on social media, he continues to post lies about the 2020 election, which he lost, while the owner of one of the major social media platforms–X, formerly Twitter–uses his position to amplify false claims about election fraud and conspiracy theories about voting machines.

It is past time, then, to take stock of the relationship between social media and the violence of January 6. What have four years of research, reporting, and investigation found?

The Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol produced a 122-page draft memo on the role of social media in the insurrection, which, while not included in the Committee's final report, has since been published online. The memo criticized key decisions by leaders of major platforms such as Twitter (X) and Facebook and explores the role that alt-right and other smaller platforms played in encouraging and facilitating offline violence on and before January 6. In short, committee investigators found that former President Donald Trump’s online utterances were a chief source of incitement; that a small number of online influencers and organizers played a disproportionate role in mobilizing the mob at the Capitol; and that key decisions by platform executives at on design, policy, and content moderation failed to stem the flood of election conspiracy theories and violent rhetoric.

Nearly four years later, social science has confirmed many of these findings. This review draws on more than 280 academic analyses exploring the relationship between social media and the insurrection. Here are our findings.

Both mainstream and alternative platforms allowed domestic extremists and prominent figures on the right to accelerate the growth of movements like QAnon and Stop the Steal, contributing directly to the insurrection.

Hal Berghel (2022) cited research by University of Chicago political scientist Robert Pape suggesting that adherence to QAnon and high rates of social media use are strong predictors of both election denial and an appetite for political violence. A joint report by Polaris and the Soufan Group suggested that online rumors about human trafficking, and especially sex trafficking of children, are a major gateway to QAnon adherence. Claire Seungeun Lee et al. (2022) compared Trump’s online speeches to subsequent hashtags used by QAnon adherents to further link the former President’s rhetoric to the movement.

In an analysis of Twitter data leading up to the Capitol attack, Padinjaredath Vishnuprasad et al. (2024) found that many election deniers were adherents to QAnon before the emergence of the “Stop the Steal” movement and that networks of rapid retweeters, copy-pasted messages, and the participation of high profile right-wing outlets and commentators were essential to the spread of these narratives. Meta’s internal analysis of Stop the Steal activity on Facebook reached a similar conclusion: just 137 “super inviters” were responsible for 67% of growth in the largest “Stop the Steal” groups, and “almost all of the fastest growing [Facebook] groups were Stop the Steal during their peak growth.” Taken together, their findings support other work, such as Rimi Nandy and Jhilli Tewary (2024), suggested that a nexus of radicalized individuals, influential public figures, and the affordances of social media platforms contributed to the insurrectionists’ motivating beliefs.

QAnon and Stop the Steal were prominent on Facebook, Twitter, and other mainstream sites, but other platforms also played an important role. Max Aliapoulios et al. (2021) showed how a combination of endorsements from prominent right-wing figures and “deplatforming” users on more mainstream services led to growth on the alt-right platform Parler before the insurrection. Wei Zhong, Catie Bailard, David Broniatowski, and Rebekah Tromble (2024) demonstrated “substantial interaction” between the Proud Boys, QAnon supporters, and white supremacists on Telegram, the largely unmoderated messaging service.

Twenty-two studies in our sample discussed former President Trump’s culpability in the insurrection. Many of these focus on Trump’s use of social media, especially Twitter (X). In summary, Trump capitalized on the new media environment to issue coded incitements to violence directed to an audience of attentive supporters in a way that is unique in the history of the presidency.

Mohd Razman Achmadi Muhammad and Norr Nirwandy (2021) wrote for the Journal of Media and Information Warfare that Trump’s use of social media challenges the news media’s traditional agenda-setting power, allowing the President to bypass traditional media and directly inspire and encourage action from his supporters online. John Allen Hendricks and Dan Schill (2024) likewise emphasized the “unfiltered and unmediated” nature of Trump’s digital communication to the public and its role in inspiring violence at the Capitol.

Helen Harton, Matthew Gunderson, and Martin Bourgeois (2022) suggested that Trump’s online activity, combined with the “ease of online discussion,” created dangerous group dynamics in which both an authority figure—the former president—and peer influencers spurred individuals to violence. Barseel AlBzour (2022) used “speech act theory” to analyze Trump’s tweets leading up to the insurrection and conclude they were understood by their audience as directives that incited violence both implicitly and explicitly.

Important gaps remain in the literature tracing social media’s influence on the insurrection. Studies focusing primarily on the design and affordances of platforms were scarce; features like algorithmic content recommendations, group invitations, or other common aspects of social media were mentioned only rarely and usually with passing references to how social media accelerated polarization, “echo chambers,” and “filter bubbles.” Internal Meta research leaked by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen suggested that Facebook (and Facebook groups in particular) has had a strong independent effect on the trend toward negative, angry political discourse online.

Rather than delving deep into the role these trends played on January 6th, though, studies were much more likely to look at user-generated content or the impact of content moderation decisions such as deplatforming. This is in contrast to the findings in the January 6th Committee social media team’s memo, which dedicated significant space to levers “upstream” of content moderation like the “break glass” measures deployed by Facebook to limit the risk of violent incitement and extremist organizing before the 2020 election. More recent work on platform design codes by University of Southern California scholar and former Meta data scientist Ravi Iyer and others explores this work in a contemporary context. Still, little empirical work has been done on how design choices facilitated January 6.

This paucity of empirical work is partially a result of the continuing opacity of the social media industry. As with other questions related to social media and politics, the lack of accessible data has done much to shape the literature on social media’s role in the insurrection. Of the 282 items collected for this case study, 136 used social media data in some way, but half of those (68) focused on Twitter (X). Uniquely among major platforms, Twitter’s API was previously accessible to researchers, a practice that ended after the platform came under Elon Musk’s ownership. But Twitter is a poor proxy for public opinion or social media as a whole, and too little scholarship on January 6 has scrutinized other platforms.

Another key gap is the connection between broadcast and social media. An exception – Muhammed and Nirwandy (2021) – demonstrated that, on Twitter, Trump actively promoted One America News Network (OANN) content and disparaged Fox News in comparison. OANN was a common news source for Capitol rioters. The internet does not exist in isolation, and research on the media environment is too often siloed into the on- and offline.

Finally, more could be done to situate January 6 historically. While shocking, the insurrection was not unprecedented. As Diren Valayden, Belinda Walzer, and Alexandra Moore argued in the Journal of Right-Wing Studies (2024), the insurrection was “one out of forty-five protests at state capitols and elsewhere in thirty-two states on that day.”

Earlier in 2020, the country witnessed several other incidents in which armed protestors breached state capitols. Moreover, these scholars pointed out that January 6 was precisely the type of event one would expect if right-wing rhetoric were taken at face value (“take our country back,” etc.). In a PhD dissertation submitted to the University of Michigan, Hanah Stiverson (2023) similarly referred to “banal fascism” and traced the history of far-right organizing in the United States. Understanding the relationship between political violence and long-running historical themes in American life is an essential part of disentangling social media’s impact on society from other trends and influences.

January 6th is in some ways a poor parallel for the risk of violence in 2024. Donald Trump is not the sitting President—he does not wield the powers of that office—and this year, officials have taken steps to secure the Capitol, an obvious target. While public support for political violence is difficult to measure, research suggests it is low among Americans of both parties. But if nothing else, the last insurrection should teach us that it only takes a small number of motivated individuals to organize for violence—and that they can, have, and will use technology to mobilize. All they lack is a clear signal to do so and an agreed-upon target. The risk is very real that Donald Trump and his associates could provide them with both in the weeks ahead.

Related Reading:

- Read the January 6 Committee Social Media Report

- Tech Platforms Must Do More to Avoid Contributing to Potential Political Violence

- Evaluating the Role of Media in the January 6 Attack on the US Capitol

- How to Reduce the Danger of Social Media Facilitating Political Intimidation and Violence

- Deplatforming Accounts After the January 6th Insurrection at the US Capitol Reduced Misinformation on Twitter

Authors