The Real Race for an AI Moratorium: Stopping Data Centers

Jenna Ruddock / Dec 17, 2025

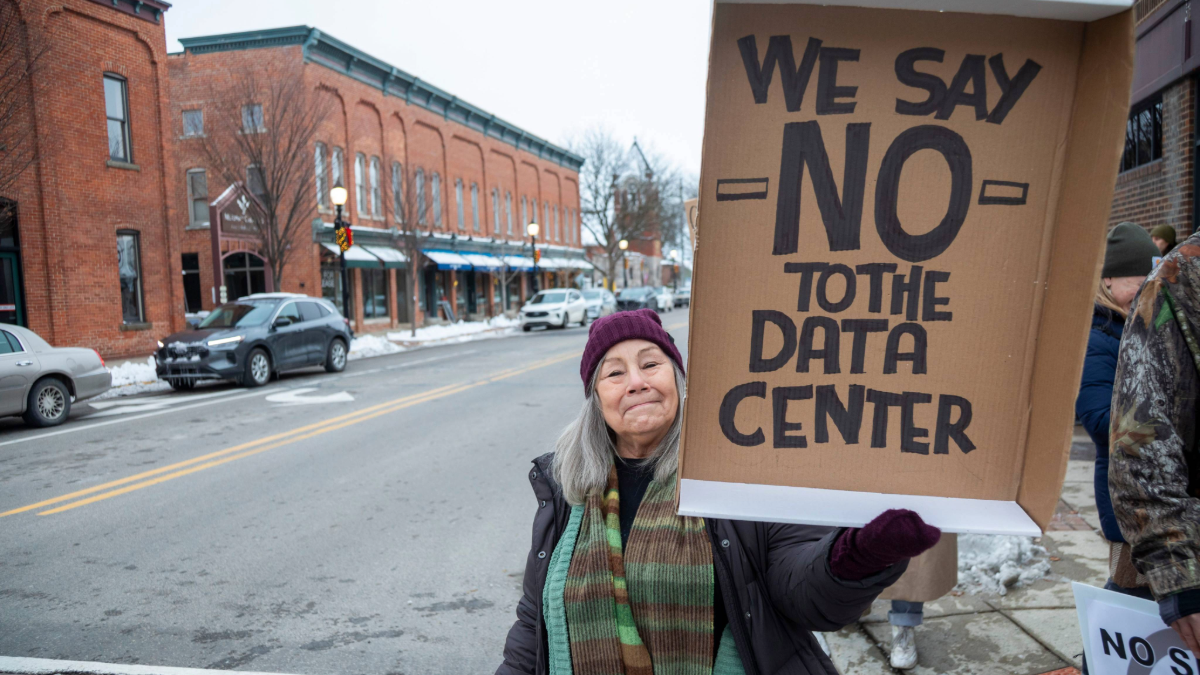

Saline, Michigan, December 1, 2025. Rural Michigan residents rally against the $7 billion Stargate data center planned on southeast Michigan farm land. Protesters say the Data Center is being fast tracked by DTE Energy, the large electric utility, and that it could raise residential electricity rates and endanger the water supply. (Photo by: Jim West/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The visuals are nostalgic small-town America: neighbors catching up at a local diner, crops being harvested in a golden hour haze, cut to the cheering crowd at a Friday-night high school football game. It’s a new ad campaign from Meta, brought to a streaming service near you, painting its hyperscale data center building spree as a welcome, beneficent investment in rural communities across the United States.

Off screen, Meta’s AI-fueled land and resource grab is being fiercely resisted by communities from northeastern Louisiana to eastern Wisconsin as they contend with the direct costs of a trillion-dollar tech company’s latest ambitions. Neighbors of Meta’s hyperscale data center in Newton County, Georgia describe issues with water pressure and quality since the facility was built – Meta reportedly now accounts for roughly 10% of the county’s total daily water use. A small town near the site of Meta’s under-construction “Hyperion” facility in Louisiana has seen a 600% increase in car crashes since the onset of construction traffic; the local elementary school closed its playground as a safety precaution. When completed, that data center campus will consume as much energy daily as New Orleans, requiring at least three brand-new fossil-fueled power plants to operate, according to the Associated Press.

Confronted with similar stakes, cities and counties across the US are pulling the emergency brake. From Maryland to Missouri, at least fourteen states are home to towns or counties that have implemented moratoriums: a complete pause on data center development. In early December, over 200 groups – from faith groups in Florida and Louisiana to physicians in Texas – publicly called for a moratorium on new data center construction nationwide. On Tuesday, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) joined the fight, announcing that he will also push for a national data center moratorium.

The Trump administration has spent its first year mobilizing to bulldoze a regulatory fast-track for these projects, building on an effort initiated by the Biden administration in its final days. But even as the White House now tries to prop up failed efforts by Congressional Republicans to pass their own version of an AI moratorium – blocking any state efforts to regulate AI, despite significant resistance from within their own party – it’s never been clearer across the country that people are prepared to fight back against the runaway data center construction fueled by Silicon Valley’s AI hype.

“We’ve entered the realm of absurdity.”

Meta is hardly alone in its rush to secure land and energy for data centers needed to power its AI ambitions. In Pennsylvania, Microsoft is driving the push to reopen the Three Mile Island nuclear facility to power its own data centers. OpenAI’s currently planned projects would collectively consume more energy than New York City and San Diego. New research forecasts that US data centers could consume as much water as 10 million Americans by the end of this decade.

“We’ve entered the realm of absurdity,” notes Julie Bolthouse, Director of Land Use for the Piedmont Environmental Council and a resident of Loudoun County, Virginia. Also known as Data Center Alley, Loudoun County has the largest concentration of hyperscale data centers anywhere on the planet – and that footprint is growing. “The goal is to slow down and figure out what in the world we’re actually doing.”

For years, communities have asked for incredibly straightforward concessions when data centers came to town. In 2021, journalists in The Dalles, Oregon wanted to know how much water local Google data centers were already using before the company built two more, given Google’s claims that The Dalles would have to expand its water system to meet the company’s growing demand. Last year, neighbors in South Memphis, Tennessee, wanted to know how many diesel generators were powering Elon Musk’s nearby xAI data center, Colossus, because diesel generators emit carcinogenic pollutants linked to respiratory illnesses and cancer. This past summer, residents of Tucson, Arizona would have liked any kind of notice that a hyperscale data center was coming to town at all.

Instead, when The Oregonian filed a public records request to learn how much water Google’s data centers in The Dalles were consuming, city officials sued to prevent the release of that information because they’d signed a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) with Google. In Memphis, the Southern Environmental Law Center had to team up with conservation organization SouthWings and fly over Musk’s Colossus with a thermal camera just to see how many diesel turbines were running without permits. Tucson residents only found out about a proposed Amazon Web Services data center weeks before a public meeting where county officials voted to rezone the land needed for the project. Developers had been in secret talks with county officials, who were bound by an NDA to not disclose Amazon’s involvement, for over a year.

Faced with this mounting record of secrecy and entitlement, and with stories about data centers’ local impacts finally being reported more widely, communities are escalating their responses. “When everything is shrouded in secrecy, there is no awareness, there is no one to complain or push back on it,” says Taylor Frazier McCollum of Landover, Maryland. Since June, Frazier’s petition to block a hyperscale data center just one mile from her house has garnered over twenty thousand signatures. She’s helped organize hundreds of residents across Prince George’s County to attend public hearings and community meetings. “The more we become aware of these projects, the more likely we are to stop them.” By September, local policymakers in Prince George’s County had implemented a six-month moratorium on data center construction.

That put Maryland on the moratorium map, joining the growing ranks of states with local moratoriums in place. In Georgia, an emerging hotspot for hyperscale data center development, at least eight towns and counties have passed moratoriums just this year. A fourth Indiana county passed a data center moratorium in early December, as companies like Amazon break ground on data centers estimated to consume as much energy as half of all Indiana households. Citizens Action Coalition Indiana has been calling for a statewide moratorium since last October: “Hyperscaler data centers are the single biggest threat to affordability, reliability, and environmental sustainability in Indiana this decade,” said CAC Program Director Ben Inskeep in a statement.

Another tool in the toolbox

Across the US, many local fights against data centers are just getting started. Most moratoriums are short-term solutions, though even a brief local moratorium can buy much-needed time for communities facing down some of the wealthiest and most powerful companies in history. Other policy and regulatory decisions can ultimately have the same effect of blocking hyperscale data center projects by targeting specific impacts like energy and water use, utility rates, and air pollution; moratoriums create the space needed for communities to work out these more holistic, longer-term solutions.

“There are different ways to pause,” Bolthouse notes. “It’s not just that we can’t provide the service – we can’t provide it in a way that doesn’t destroy everything else.”

She points to her backyard: “At this point, in our area, we’ve got 47 gigawatts of load that has been contracted with Dominion Energy, on a grid that has a peak energy usage of 23 gigawatts…That’s why we need to consider pauses and policy changes that actually say: We’re going to step back and stop approving new load, and we’re going to think about how in the world we’re going to meet that load in a way that makes any kind of sense at all.”

And while moratoriums send a clear message, they are far from the final word. “A lot of people feel like the battle is over because we got the moratorium,” says Frazier. “When we talk to people and they’re following the story loosely, they’re like oh, well I saw on the news that there’s a moratorium in place, so I think we’re good in Landover, right?

“No, not exactly.”

Even as data center opposition emerges as a leading electoral issue – and often a decisive one, cutting across the political spectrum in races from Virginia to Georgia – policymakers are still working to clear the path for the tech companies and private equity outfits willing to continue sinking billions into these projects. There are few signs that the eye-watering data center investment announcements this past year by companies like Meta, OpenAI, and Blackstone-owned QTS will slow in 2026, even though these investments are at the center of growing speculation about an AI bubble – and even as these projects are increasingly financed by debt.

The final frame of Meta’s ads read: “Meta is investing $600 billion in American infrastructure and jobs.” Like the generically wistful scenes building up to this final claim, it obscures the reality on the ground – and on the horizon.

From Louisiana to Iowa, communities where hyperscale data centers ultimately are built will see a vanishingly small fraction of any projected profits due to massive subsidies, even as communities are saddled with soaring utility rates and the public health costs of noise and air pollution. The nod to job creation rings similarly hollow, especially as Meta soft-launches its latest round of layoffs before the holidays after yet another speculative bet – the metaverse – has dramatically failed to pay off. After construction, most data centers create remarkably few permanent jobs; a factor communities are weighing against the tech industry’s persistent promise that AI will be used by executives to replace the jobs people do have. And as resistance and regulations escalate here on Earth, tech billionaires are already musing about data centers in space.

“I don’t think a moratorium is too extreme,” says Frazier. “I think the AI bubble is what’s extreme.”

“Saying hey, this kind of business can’t operate here – I don’t think that’s something that we can afford to not use as a bit of leverage.”

Authors