The Path to a Sovereign Tech Stack is Via a Commodified Tech Stack

David Eaves / Dec 15, 2025

Frontier Models 1 by Hanna Barakat & Archival Images of AI + AIxDESIGN / Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

There is growing and valid concern among policymakers about tech sovereignty and cloud infrastructure. A handful of American hyperscalers — AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud — control the digital substrate on which modern economies run. This concentration is compounded by a US government increasingly willing to wield its digital industries as leverage. As French President Emmanuel Macron quipped: "There is no such thing as happy vassalage."

While some countries appear ready to concede market dominance in exchange for improved trade relations, others are exploring massive investments in public sector alternatives to the hyperscalers, advocating that billions, and possibly many many billions, be spent to on sovereign stack plans, and/or positioning local telecoms as alternatives to the hyperscalers.

Ironically, both strategies may increase dependency, limit government agency and increase economic and geopolitical risks — the very problems sovereignty seeks to solve. As Mike Bracken and I wrote earlier this year: "Domination by a local champion, free to extract rents, may be a path to greater autonomy, but it is unlikely to lead to increased competitiveness or greater global influence."

Any realistic path to increased agency will be expensive and take years. To be sustainable, it must focus on commoditizing existing solutions through interoperability and de facto standards that will broaden the market (and enable effective) national champions. This should be our north star and direction of travel. The metric for success should focus on making it as simple as possible to move data and applications across suppliers. Critically, this cannot be achieved by regulation alone, it will also require deft procurement and a willingness to accept de facto as opposed to ideal standards. The good news is governments have done this before. However, to succeed, it will require building the capacity to become market shapers and not market takers — thinking like electricity grids and railway gauges, not digital empires.

The original sin of cloud computing

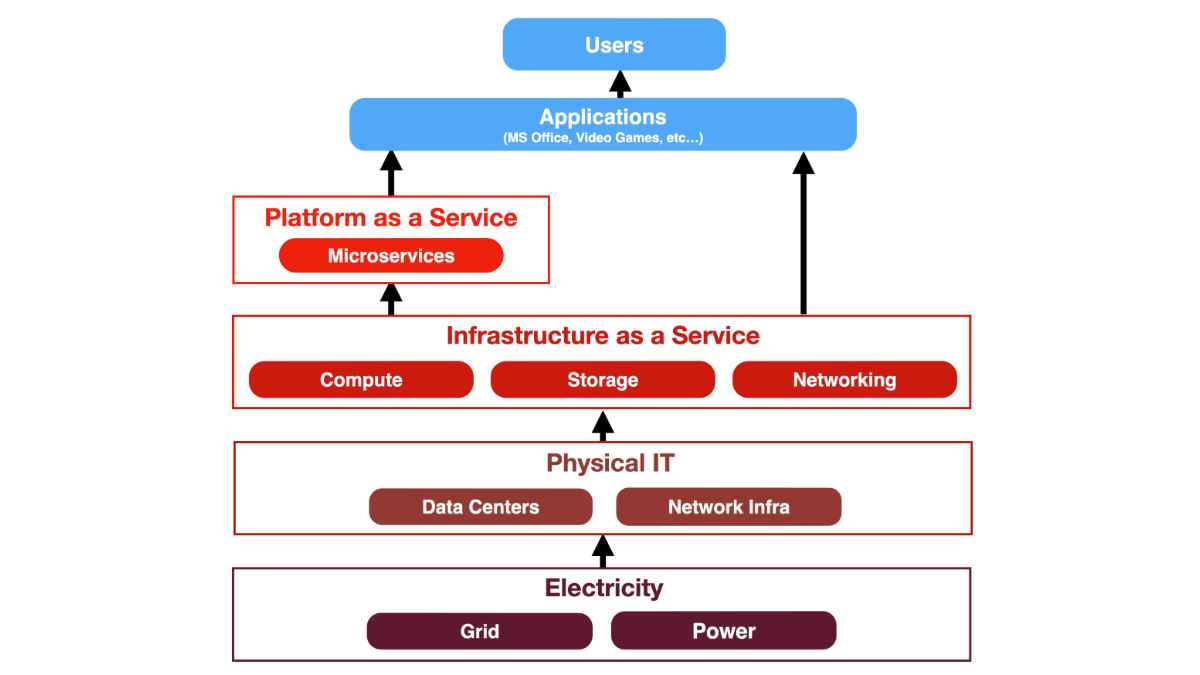

Cloud providers limit customer agency through two chokepoints: Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS). IaaS provides processing, storage, and networking — like a scaled-up laptop. PaaS is like an operating system, composed of useful microservices that make building applications easier.

These layers sit atop two already commoditized foundations: power and internet connectivity. The 20th century triumph was making power and data transmission universal and interchangeable.

When AWS launched in 2006, its S3 storage bucket was the first infrastructure service — essentially a big hard drive accessible anywhere. But in 2008 when it launched Azure Microsoft created its own incompatible storage system rather than adopting S3. This "original sin" set each cloud company on a path toward proprietary infrastructure. Lock-in wasn't a bug — it was a feature.

The hyperscalers doubled down. Their services remained incompatible, creating enormous value while maximizing rent extraction. Migration between providers remains labor intensive, developers must reconfigure data and edit entire code bases. Moreover, a Google Cloud expert is not an AWS expert. Organizations must maintain expertise in different hyperscalers solutions, or focus on one, deepening lock-in. These companies invest heavily in developer training because it becomes a kind of career lock-in for the individuals trained in a particular cloud ecosystem — their microservices are incomprehensible dialects of ostensibly the same language.

Figure: The layered digital infrastructure stack, from electricity to users. Credit: David Eaves.

The costs are real. I recently advised a government agency that mandated AWS only for compute and storage, not platform services, to limit lock-in. But whenever projects arose, staff faced a choice: code functionality themselves at great expense, or leverage AWS's platform services at far lower cost. The financial logic was irresistible.

This story captures the dilemma. Effective infrastructure can radically reduce costs while improving resilience. But every choice locks developers — and ultimately entire economies — in and diminishes agency.

Regulating infrastructure: railway gauges

In the late 1800s, governments faced another infrastructure crisis. Railways consumed enormous capital and reshaped societies. They would clearly be essential economic inputs, but different railways used different gauges, creating multiple incompatible networks. Trains were restricted to compatible networks; people and goods had to be unloaded and reloaded.

Governments stepped in by reducing choice. In Britain, after an 1845 Royal Commission, Parliament mandated in 1846 that future railways use Stephenson's standard gauge — not because it was better, but because it was most widely adopted.

The US nudged rather than mandated. The Pacific Railroads Act of 1863 specified that federally funded railways would use standard gauge. Industry responded: in May 1886, tens of thousands of workers converted 14,000 miles of Southern Railway from 5-foot gauge to standard gauge in just over 36 hours.

There's an interesting parallel. The UK's first steam powered railway launched in 1825; regulations came 20 years later. AWS launched S3 nearly 20 years ago. Yet it's hard to imagine governments today being equally decisive in shaping the cloud market.

Regulating infrastructure: the JEDI contract

Interestingly, an effort to commoditize both IaaS and PaaS has been tried. The Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) procurement — a $10 billion Pentagon contract for cloud capacity, likely represents the most ambitious market shaping exercise for hyperscalers to date. Its architects saw an agency problem. With a $950 billion budget, vendor lock-in costs real dollars in rent extraction and operational flexibility.

JEDI was designed to nudge industry toward standards in two ways. First, JEDI allowed joint bids from multiple vendors — if their offerings were interoperable. Second, even with a single winner, the other cloud operators would likely have needed to make their services compatible to work with the military once the contract ended. Any winner would become a de facto standard within the military, a standard that might have spilled out and become government-wide, and possibly private sector-wide.

The hyperscalers attacked JEDI as anti-competitive. But creating a standard would have increased competition by effectively converting a proprietary infrastructure into a de facto public standard. This terrified some cloud providers, who spent rabidly on lawsuits and lobbying to kill it. To this day, many of their lobbyists insist government entities must have multicloud strategies — that talks about portability or interoperability, without providing any clear mechanism around how it would be realistically achieved.

JEDI is worth studying because it came close to succeeding. Its biggest challenge was maintaining government alignment as the presidency shifted. It also serves in sharp contrast to Europe's Gaia-X and Data Act, which differed fundamentally: neither brings buying power to incentivize adoption, and either rely on voluntary or new standards rather than recognize existing ones. De facto standards almost always beat untested de jure standards.

A market shaping approach to commodification and sovereignty

We're at a critical juncture. Rightly fearful of the hyperscalers, the biggest risk is that governments adopt an industrial policy approach, turning to domestic providers — typically telcos — who will lock them into niche, proprietary solutions that will limit state capacity and drive up costs. This moves us in exactly the wrong direction — more bespoke infrastructure making provider switching harder.

Building domestic capacity may be part of the puzzle, but it isn't the solution. It must be an element in a strategy focused on maximizing agency and driving down costs. The strategy should emphasize interoperability: reducing lock-in opportunities by commodifying mature technologies. Re-use and align around what has traction. Boost de facto standards.

It is likely that a multitude of strategies will be needed to drive portability and interoperability. And we should do everything to encourage technologists to pursue this direction of travel. Below are two potential starting points.

Bottom-up: standardize storage

Governments should do to storage what the Pacific Railroad Act did to railways. Mandate that any government-funded cloud provider must offer storage interoperable with S3 buckets, certified by a national standards body. This need not be retrospective — Azure needn't abandon Blob storage, just offer an S3-compatible option if it wants government business. Many other providers already do.

This signals government seriousness about reshaping markets through interoperability. It forces incumbents to choose: interoperate or leave. Critically, it forces domestic champions to be interoperable, lowering lock-in risk and minimizing any "sovereignty premium."

It acknowledges reality: after 20 years, S3 is already the standard. Many later arrivals, like Cloudflare, built compatible services. This approach recognizes a winner and could initiate a process that shifts a de facto standard into becoming an open one.

Finally, it's easiest to coordinate internationally. Multiple governments could align with minimal coordination.

Top-down: commodify platform services

Alternatively, governments could commodify microservices essential for sectors like government services, healthcare, or defense. Rather than relying on proprietary platform services, governments could define open services available across any provider.

Emergent platform services already exist: the UK Government's Pay, Notify, and Forms services; India's Inji and Digit. These are exactly what governments need. India is following this playbook; Digit can be downloaded and run locally or offered as a cloud solution by states, the national government, or conceivably private players. Local governments can switch providers with minimal friction.

South Africa's MyMzansi app used these open platforms, enabling it to be built in weeks rather than years. With more investment and coordination, these could become de facto standards required in cloud procurement — effectively recreating JEDI across multiple jurisdictions.

This approach would align government and industry around key components, driving costs down while improving effectiveness and security. It may be less painful for hyperscalers to implement, though governments wouldn't need their adoption — a new market of platform providers could sit atop existing infrastructure. But we should want hyperscaler participation. Our goal isn't to destroy the sector but to tame it through inducements where possible, and laws where necessary.

Risk mitigation and tradeoffs

For most, and possibly all countries, creating sovereign stacks will be prohibitively expensive, and carry significant risk of failure, to say nothing of the real costs of losing interoperability and geographic flexibility. We should also be careful about sovereignty definitions that prevent leveraging the internet's distributed power. All policy, and much software design and architecture, is about tradeoffs: “Design is about choosing how you will fail.” Protecting against the overreach of a single large company or country influence is an important risk to design against. However, alternative approaches have other failure modes. South Korea may have permanently lost 858TB of critical government data because of failed redundancy in its sovereign cloud. Many Ukraine's data centers have been attacked. Geopolitical risks, climate change, and energy redundancy mean the safest place for your country’s data may be... on a server in another country. Countries facing existential risks like Ukraine and Estonia reached that conclusion. Increasing "control" at resilience's cost is a bad tradeoff.

More profoundly, we need options enabling agency for more than wealthiest or largest countries. Sovereign stacks work for Europe, the US, China, and maybe India — but even countries the size of Brazil may lack the talent, resources, market size and skills. Hard to imagine they are an option for countries with small populations or GDP, or unreliable power grids. They may not be feasible even for middle powers like South Africa, Canada, or Indonesia. A digital sovereignty paradigm excluding 50-100+ countries is hardly a solution.

Conclusion: agency through standards

There are no easy solutions — only challenging tradeoffs. The aim of this post is to expand the range of options and show governments they're neither as weak nor incapable as they believe. The goal shouldn't be destroying the hyperscalers — it should be taming them through the tools used for railways and electricity: strategic standardization backed by procurement power and market forces.

This requires reframing. The question isn't "Can we own our stack?" but "Can we move our workloads?" If there was a large and liquid market of cloud provision, the conversation about sovereignty would look very different. Sovereignty through ownership risks being a fantasy for all but the wealthiest. Sovereignty through interoperability may be achievable for nearly everyone.

Two promising leverage points exist: standardizing storage around S3 or commodifying platform services essential for government operations. Either or both would force providers to compete on price, performance, and service rather than lock-in, ensuring domestic champions are interoperable from day one. They could also serve as a basis for loose or even more coordinated cooperation between governments aligned around this approach.

None of this is easy. It requires governments to coordinate across borders, resist quick fixes through domestic monopolies, and maintain discipline over decades. Governance of shared standards remains unsolved — we have few models for governments collaboratively managing critical software infrastructure.

But the alternative is worse. Countries accepting permanent lock-in will scramble to move services when the next geopolitical crisis hits. Those spending billions on incompatible sovereign stacks may find they are harder and more expensive to create than imagined, and worse, may be gilded cages even if they succeed. And those — the majority — without resources for either will be left out entirely.

Governments shaped railway markets in the 1800s and electricity in the 1900s. They have the precedent and leverage to shape the cloud market today. The question shouldn’t be about imagination — it's about capacity and will.

Authors