The Online Safety Act: Royal Assent Was Only the Beginning

Tim Bernard / Nov 12, 2023Tim Bernard is a tech policy analyst and writer, specializing in trust & safety and content moderation.

The genesis of the UK Online Safety Act can be dated to 2017, and so when Parliament finally approved the bill in September and it received royal assent last month, it may have felt like the end of a very long road for the legislation.

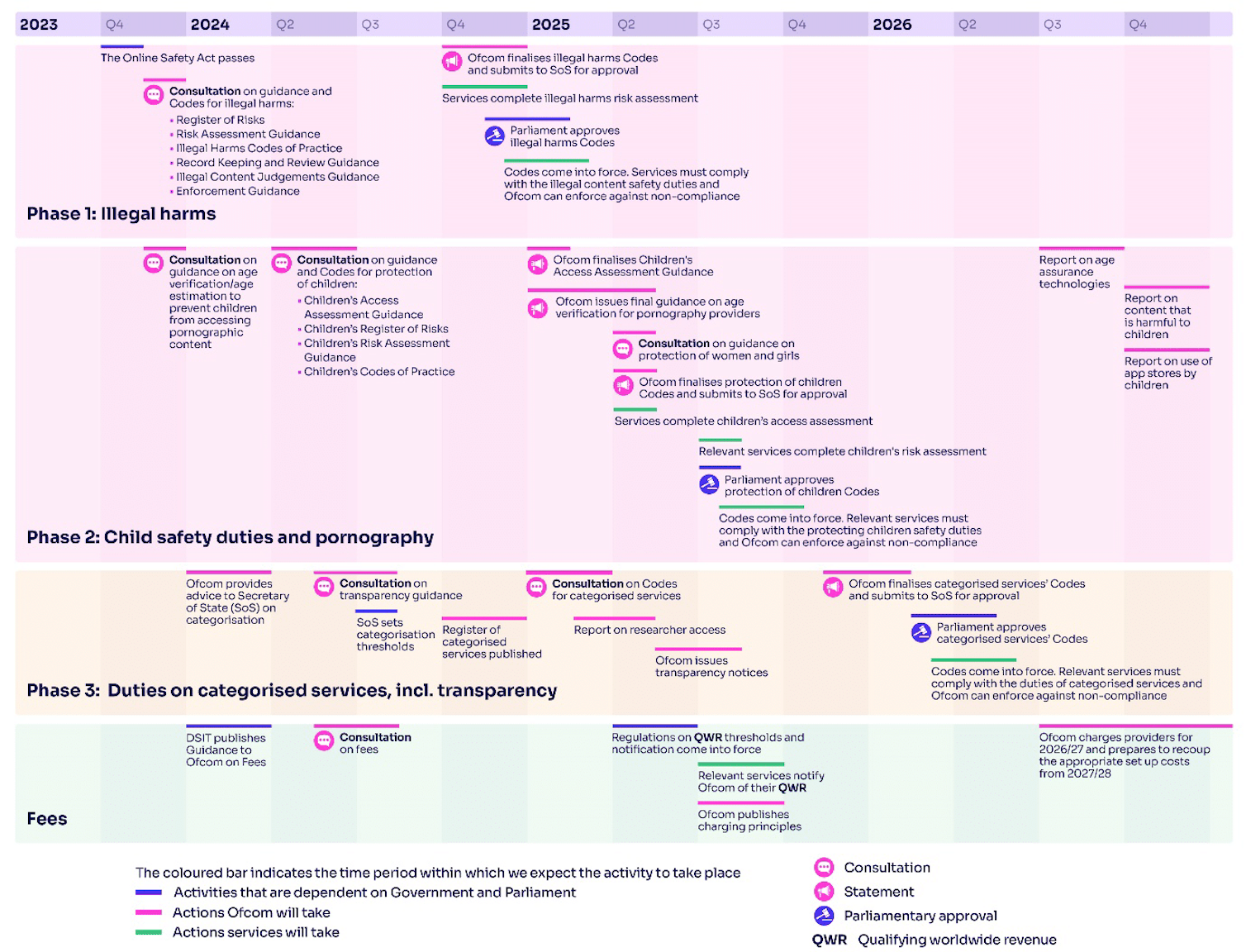

That “end” would have been a mirage. The Online Safety Act provides for Ofcom, the British telecoms regulator, to draft codes of conduct in several critical areas, and leaves significant discretion in how the act is to be interpreted and enforced. Each code of conduct will be released as a draft for consultation, and then the finalized versions will each require parliamentary approval. Ofcom’s timetable projects that the final codes will not be finalized and take effect until some time in 2026.

Although this may seem like a lengthy process, the release of the first tranche of draft guidance and codes casts the timeline in a rather different light. This is material presented for consultation, and tech policy expert Mathias Vermeulen counted 1714 pages of substantive content in the release. Comments are due by February 23, 2024, and so the time frame is not particularly generous, especially when considering that the materials drop for the next phase is scheduled for December.

What is in this consultation package?

The topic of this phase is online services’ duties to prevent illegal harms, and consists of six “volumes” and sixteen annexes. Though the document package is very long and only in draft form, a very cursory review begins to answer some big questions that have loomed over this legislative process for years. A lot of responsibility has been placed on Ofcom to not interpret some of the Online Safety Act’s more controversial provisions in such a way as to place undue burdens on industry or to negatively impact privacy and freedom of speech.

Proportionality

Ofcom asserts that over 100,000 digital services are in scope for the Online Safety Act. With much of the public conversation around the bill focused on the largest social media platforms, especially Meta’s Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, and adult services such as OnlyFans, some critics warned that smaller companies would be saddled with punishing requirements for which they lacked the resources to handle.

In recognition of this, the Act contains the word “proportionate” fifty-three times. Of course, determining what is proportional involves significant judgment. The draft materials start by making some clear differentiations, dividing user-to-user services into six categories: the first dimension is “large” / “small,” where the dividing line is 7 million monthly UK users. The second dimension is based on the required risk assessments, where “low risk” means a designation of low risk for all harms in Ofcom’s rubric, “specific risk” means medium or high risk for one particular harm, and “multi-risk” means medium or high risk for more than one category of harm, which means the service is then treated as broadly high-risk. Ofcom also reaffirms that they will take risk and size into consideration when considering enforcement actions.

Automated content moderation

A last-minute scramble of public statements allowed defenders of end-to-end encryption to stand down from their vehement opposition to the Online Safety Bill, despite no changes to the bill itself. These revolved around the potential for platforms to be required to use certain technologies to scan for illegal material. The broader issue of requiring general monitoring, i.e. scanning all content posted to a service, is also controversial. The draft guidance does require some scanning, but only for (1) easy consensus areas of harm (i.e. CSAM and fraud), (2) only for platforms with specific risks in these categories, (3) only in technologically straightforward ways, and (4) specifically excluding end-to-end encrypted environments.

Illegality Judgment

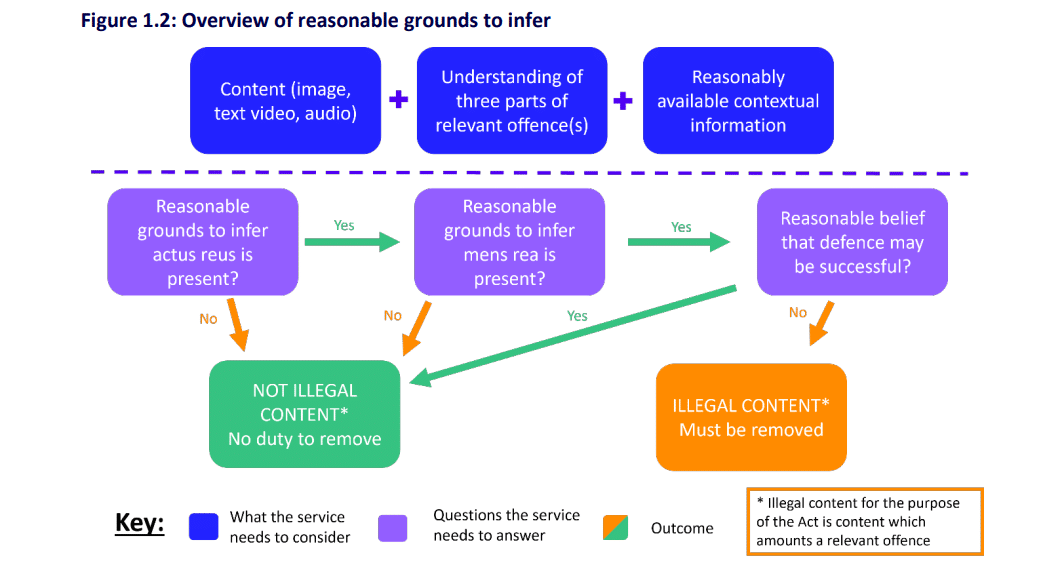

When considering which content must be removed under the Online Safety Act as illegal— which includes not just the over 130 priority illegal offenses mentioned in the law, but also anything illegal under UK law that is reported to the platform—they must apply what the guidance admits is “a new legal threshold”: “reasonable grounds to infer,” as well as to make use of “reasonably available information.” There is an in-depth exploration of what these terms ought to mean in the documentation.

Further, there is a 390-page annex containing the Illegal Content Judgements Guidance, which goes into incredible detail regarding how to adjudicate priority offenses. As an illustration, it explains that a curved blade of over 50 cm in length made before 1954 is considered an antique for the purposes of a defense against its classification as an illegal offensive weapon (p.108). These adjudications, of course, all have to be done “promptly”!

It is noted that many services will not have to really do the illegality judgment, if they instead choose to “draft their own terms and conditions in such a way that at a minimum all content which would be illegal in the UK is prohibited on their service for UK users and make content moderation decisions based on their terms and conditions.” Given the difficulty of performing the illegality judgments, it does seem like the Online Safety Act regime will result in pressure on platforms to systematically exceed the requirements of British law in their own content guidelines. In other words, platforms may err on the side of prohibiting content that may potentially be illegal rather than just following the letter of the law, on top of whatever rules they decide for themselves.

Age Assurance

Even though the next phase will focus on measures relating to protecting children, child sexual exploitation does come up in this guidance. A portion of the risk mitigations section is dedicated to prevention of grooming by implementing safeguards to prevent unknown adults contacting minors. These safeguards are to apply only to accounts controlled by under-18s, which raises the incredibly thorny question of how the platforms should know which ones those are. Even as the materials cite research on the unreliability of self-attestation for age assurance, “[f]or now,” Ofcom writes “these [measures] would only apply to the extent that a service has an existing means of identifying child users and would apply where the information available to services indicates that a user is a child.”

Policy Objectives and the Reasonable Regulator

The drafting process for the Online Safety Act was widely criticized as the length of the bill grew and populist posturing by MPs was all too common. In contrast, Ofcom has staffed up with trust and safety professionals and other technocratic experts, and the depth of its commitment to working out how to implement the stipulations of the Online Safety Act realistically is now evident.

“[O]ur first Codes aim to capture existing good practice within industry and set clear expectations on raising standards of user protection, especially for services whose existing systems are patchy or inadequate. Each proposed measure has been impact assessed, considering harm reduction, effectiveness, cost and the impact on rights.” (emphasis added)

It makes a lot of sense to set the baseline for safety at existing best practice; after all, this is what has been proven as both effective and implementable. However, these practices will typically be found amongst well-resourced incumbents. The burden for applying these more universally will fall unevenly on up-and-coming competitors, even though much of the harm is located at the big platforms due to their scale, despite already applying many best practices.

It is heartening that Ofcom has also stated its intention to individually supervise the largest and most risky services in scope to guide and encourage them to improve based on their specific circumstances. The broadness of the Online Safety Act may be its biggest weakness, and so Ofcom will have the challenge of developing its implementation so as to achieve the goal of improving online safety while avoiding the pitfalls of unrealistic or draconian requirements on one side and incumbent entrenchment on the other.

Authors