The Need for Race-Conscious Platform Policies to Protect Civic Life

Daniel Kreiss, Bridget Barrett, Madhavi Reddi / Dec 13, 2021Daniel Kreiss, Bridget Barrett and Madhavi Reddi-- researchers at the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill-- make an affirmative argument for race-conscious, as opposed to color-blind, platform policies in all areas that relate to institutional politics.

A recent Washington Post report revealed that in 2020 Facebook’s internal researchers produced extensive evidence about how hate speech on the platform disproportionately affected racial and ethnic minorities, even as its systems most effectively policed speech against whites and men. As the Post concluded about the internal debate over how to address this:

The previously unreported debate is an example of how Facebook’s decisions in the name of being neutral and race-blind in fact come at the expense of minorities and particularly people of color... One of the reasons for these errors, the researchers discovered, was that Facebook’s “race-blind” rules of conduct on the platform didn’t distinguish among the targets of hate speech.

In response, Facebook tried a more race-conscious approach. In addition to explicitly mentioning race in its hate speech policies for the first time, in December 2020 Facebook also updated its hate speech algorithm to prioritize detecting anti-Black comments over anti-white comments. Hate speech featuring remarks about “men,” “whites,” and “Americans” could still be reported, it would now just be the lowest priority for the company to address. The company leadership’s concern over conservative backlash was well-founded. In response to these changes, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley decried that the company moved away from “neutrality” and “is openly embracing critical race theory, which rejects the principle of colorblind rule and law enforcement in favor of open discrimination.”

Senator Hawley’s comments reveal a “colorblind ideology.” This ideology holds that racism has a small effect on social life, that racial social differences are the result of culture or somehow natural, or that abstract principles are more important than addressing social inequality. Hawley perfectly captures the latter in arguing that the “neutrality” of policies should trump any recognition of the different scale and effects of the harms of hate speech on non-white people.

As we show below, social media platforms rely heavily on a colorblind approach to their content policymaking. While Facebook has made steps in the right direction in the context of hate speech, recently the company banned ads targeted by race, sexual orientation, and religion. This colorblind policy is guided by the abstract principle of preventing abuse. While it sounds reasonable on its face, ultimately this policy fails to distinguish between abusive or anti-democratic ad targeting, on the one hand, and pro-social or pro-democratic targeting based on race, sexual orientation, or religion, on the other. To take an example, running targeted ads to whites who interacted with racist content should run counter to Facebook’s policies, while targeting Black Americans to promote voting should be encouraged. By failing to distinguish between these things or consider the democratic ends of the content being targeted, Facebook arrived at a content-neutral way of policing interactions on its platform that will ultimately disadvantage efforts to reach harder to mobilize voters.

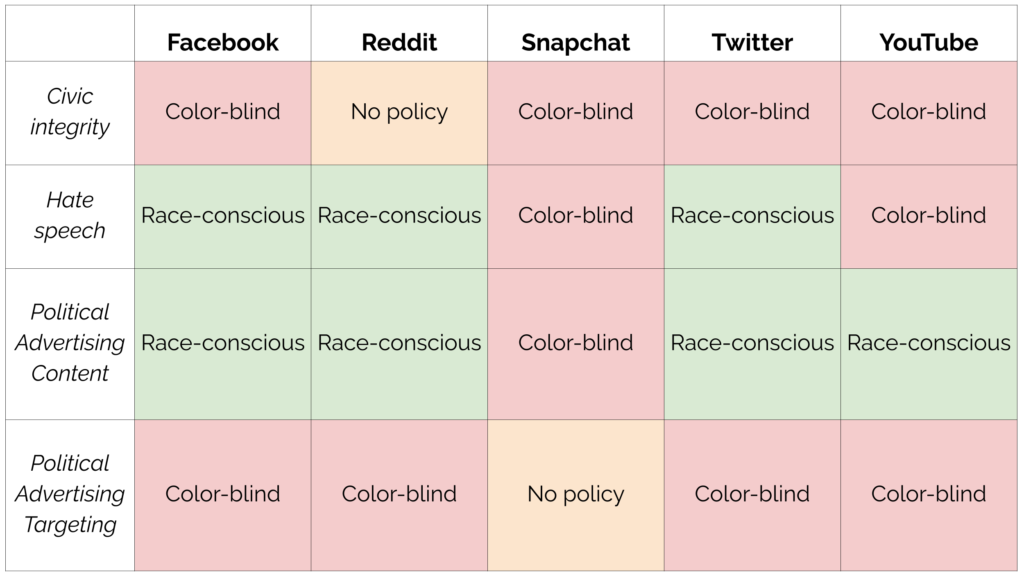

Facebook is hardly alone in this approach. Here, we make an affirmative argument for race-conscious, as opposed to color-blind, platform policies in all areas that relate to institutional politics. As part of the UNC Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life’s ongoing research into the policies of Facebook (and Instagram), Reddit, Snapchat, Twitter, and YouTube, we asked how these companies’ content moderation policies related to institutional politics in the United States address (or fail to address) race and ethnicity. Our hope is that by naming an approach to platform policies as ‘race-conscious,’ and advocating for it, we can give coherence and shape to a defined framework governing the relationship between platforms and institutional politics.

We develop and then apply these concepts of ‘race-conscious’ and ‘color-blind’ policies to analyze social media platform community guidelines (which government officials, candidates, activist groups, and members of the public are subject to), advertising policies (which political advertisers are subject to), and stand-alone civic and hate speech policies for their degree of race-consciousness versus color-blindness. The latter category includes policies relating to the census, elections, and other civic processes (civic) and rules about attacking groups of people (hate speech). We also want to acknowledge that, while important, we cannot determine how race-conscious enforcement of these policies may or may not be given the opacity of technology platforms.

Broadly, we find deep inconsistencies in platform approaches to race-consciousness and color-blindness. Especially of note is that no platform’s civic integrity policies were explicitly race-conscious, which means they fail to explicitly protect “Black voters,” “African Americans,” or other historically vulnerable groups in their policies. This is especially striking in the context of Black voters, who have historically been the primary targets of white voter suppression and discrimination efforts in the United States. We recognize that this failure to be consistently and systematically race-conscious is likely due to a number of important factors. They include the global scope of many platforms - these companies need to create policies that can work in many different national contexts – and the challenges of making nuanced policy determinations and enforcement decisions at scale. That said, regardless of these challenges, we believe that the consequence of color-blindness is a set of political policies that threaten democratic inclusion.

In the following, first we outline how we define race-consciousness and develop an extra scrutiny standard that accounts for historical and structural patterns of differences in social power. Then, we evaluate companies’ existing policies according to this standard, showing the ways they have succeeded, and failed, at adopting race-conscious policies and enforcement. Third, we outline a few examples for moving forward and detail the stakes involved.

Platforms and Race-Conscious Civic Policies: An Extra Scrutiny Standard

We believe that multiracial democracies require robust forms of race-conscious policies from the platforms that now play such a central role in civic affairs in countries around the world. The 2020 Civil Rights Audit of Facebook made an extensive case for why race-conscious policies (without using that term) are crucial for democracy and outlined how the company has a long way to go towards protecting civil rights. As the Civil Rights Audit detailed, Facebook should create positions that focus on social equity in content moderation decisions; it should train content moderators more in social contexts to protect civil rights; and, cases for content moderation and enforcement can be prioritized in different, more equitable ways that account for social vulnerability and harm. These are race-conscious recommendations that account for differences in social power. In adopting an equity standard, the Civil Rights Audit expressly recognizes that there are differences between groups, and this requires proactive measures to address them.

In our definition, race-conscious policies account not only for race and ethnicity, they go beyond abstract principles to specifically account for unequal social power. In other words, being race-conscious means accounting for the fact that some groups are at risk for the greatest harms given historical and structural forms of power, and prioritizing explicit protections and enforcement on this basis.

Even more, we think that to be truly race-conscious platforms should adopt an extra scrutiny standard to guide content moderation, including the interpretation of policies and carrying out of enforcement decisions to protect the most vulnerable. Our inspiration is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which provided extra scrutiny of changes in electoral administration in states with historical racial discrimination in electoral politics. The Voting Rights Act did not treat all races and ethnicities and states equally, but expressly accounted for historical patterns of discrimination. Adapting this race-conscious standard for content moderation would require platforms to pay extra scrutiny to content that has the potential for disproportionate harms to racial and ethnic groups based on historical and structural forms of discrimination and power in the United States.

In conceptualizing race-conscious policies and proposing the adoption of this extra scrutiny standard, we are arguing for a race-conscious approach to content, targeting, and enforcement to help platforms fulfill the spirit of their existing civic integrity and hate speech policies. As such, platforms themselves will have to determine whether things such as targeting Black Americans constitutes an attempt at voter suppression or something else entirely, such as promoting voter registration. But they will be doing so in a context where content and targeting is receiving extra scrutiny for the possibility that they will cause civic harms in the context of the racial history of the United States, where non-white groups faced legal and extra-legal forms of discrimination that robbed them of their speech and votes.

The State of Race-Conscious and Color-Blind Policies

To determine how widespread race-conscious policies are, we analyzed the policies of social media platforms that relate in some way to institutional politics - to our eyes the area of greatest concern. There are no standardized categories of social media policies, so we created relevant categories inductively. As detailed above, our “civic integrity” category captures the rules that pertain to protecting the census, elections, or other civic processes from interference and misinformation. Our “hate speech” category captures the rules about attacking groups of people. Some platforms have rules about how ads can be targeted while others focus mostly on the content of the ads, so we broke advertising policies into those two categories.

Following our definition above, we labeled as ‘race-conscious’ policies that either explicitly mention particular racial groups, or reference extant racial social hierarchies or specifically vulnerable populations. By ‘color-blind,’ we mean that the policy does not acknowledge race or assumes that the protections and/or restrictions offered through policies should apply equally to everyone without regard for the systemic inequalities that impact various racial groups differently.

Admittedly, these policies do not mean perfect-- or even good-- enforcement. However, they are a first step towards giving the public (and platform employees) the ability to hold platforms accountable to their own stated rules, and in the absence of enforcement data we start here.

Civic Integrity

Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat and YouTube’s policies relating to civic integrity do not mention race even though historically the primary group in the United States subject to voter suppression efforts is Black Americans, and more broadly racial minorities are disproportionately targeted with content designed to depress turnout through political misinformation online. Reddit does not have policies related to civic integrity.

Hate Speech

All platforms have updated their hate speech policies in the past few years.

Facebook’s now more thorough policy, updated after its Civil Rights Audit was published in summer of 2020, defines hate speech as “a direct attack against people on the basis of what we call protected characteristics: race, ethnicity, national origin, disability, religious affiliation, caste, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity and serious disease” and provides specific examples of prohibited content that include groups who are typically targeted worldwide. Facebook makes explicit reference to historical forms of social and political power: “We also prohibit the use of harmful stereotypes, which we define as dehumanizing comparisons that have historically been used to attack, intimidate, or exclude specific groups, and that are often linked with offline violence.” And, the company explicitly details a set of historical “dehumanizing comparisons, generalizations, or behavioral statements” relating to vulnerable groups. While some of these policies are abstract, the inclusion of specific statements of historical vulnerability qualify as race-conscious.

Reddit has a race-conscious policy because it centers an assessment of vulnerability, even though it is not clear which groups actually fall into this category. The company prohibits “promoting hate based on identity or vulnerability” and defines “marginalized or vulnerable groups” as “groups based on their actual and perceived race, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, immigration status, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, pregnancy, or disability. These include victims of a major violent event and their families.” The language of this policy clearly implies that the company has a racial analysis.

Twitter states that “you may not promote violence against or directly attack or threaten other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, caste, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease. We also do not allow accounts whose primary purpose is inciting harm towards others on the basis of these categories.” Twitter also expressly references that “research has shown that some groups of people are disproportionately targeted with abuse online” and details these groups - making these policies race-conscious.

In contrast, we classify Snapchat and YouTube’s rules as color-blind. While these platform policies explicitly mention race and ethnicity, among other things, they fail to distinguish between socially dominant and dominated groups. As such, they equate speech directed at or about very differently positioned social groups, preserving color-blindness through the lens of abstract ideals. For example, Snapchat does not allow “Hate speech or content that demeans, defames, or promotes discrimination or violence on the basis of race, color, caste, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, or veteran status, immigration status, socio-economic status, age, weight or pregnancy status.” YouTube prohibits “promoting violence or hatred against individuals or groups based on any of the following attributes: Age, Caste, Disability, Ethnicity, Gender Identity and Expression, Nationality, Race, Immigration Status, Religion, Sex/Gender, Sexual Orientation, Victims of a major violent event and their kin, Veteran Status.”

Political Advertising Content

All of the major platforms have color-blind political advertising content policies in taking an approach that applies an abstract ideal to content without acknowledgment of social differentiation and social power.

Advertisements on social media platforms are subject to platforms’ community guidelines as well as additional advertising policies. This means that all platforms ban the types of hate speech defined above in the content that advertisers promote. That said, political advertising is often subject to still another layer of advertising-specific policies as well. Social media platforms have widely recognized the history of racial discrimination and predatory practices in advertising and have developed policies to stop it. These policies are primarily developed for advertisers of commercial goods, not political advertisers. However, these policies still generally apply to political ads and have been a reason why some racist political ads have been removed.

All of which means that advertising is a small subset of content that is paid and therefore generally has more specific and extensive rules than organic content. Social media platforms generally write country-specific advertising policies and create the categories for the groups of people built into the advertising system (targeting, discussed in the next section).

For example, Facebook states that “Ads must not discriminate or encourage discrimination against people based on personal attributes such as race, ethnicity, color, national origin, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, family status, disability, medical or genetic condition” in its “discriminatory practices” advertising policy. While this is an abstract statement, when coupled with Facebook’s hate speech content rules naming particular groups the policy is race-conscious. While Twitter has banned most forms of political advertising, the company’s advertising rules expressly prohibit the promotion of hateful content on the basis of race (among other groups) as well as mocking events that “negatively impact” a protected group. Organizations that associate with promoting hate are not allowed to advertise on Twitter. When coupled with hate speech rules, this makes Twitter’s policies race-conscious. Similarly, political advertisers on Reddit have to adhere to the company’s political and general advertising rules, including its hate speech policies – making this policy race-conscious.

Oddly, while YouTube’s hate speech policy does not distinguish between groups, its advertising policies do, making them race-conscious. YouTube does not allow advertising “Content that incites hatred against, promotes discrimination of, or disparages an individual or group on the basis of their race or ethnic origin, religion, disability, age, nationality, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or any other characteristic that is associated with systemic discrimination or marginalization.”

Snapchat, meanwhile, embraces abstraction in explicitly prohibiting ads that “demean, degrade, discriminate, or show hate toward a particular race, ethnicity, culture, country, belief, national origin, age, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity or expression, disability, condition, or toward any member of a protected class” in its “Hateful or Discriminatory Content” advertising policy

Political Advertising Targeting

The words, images, and audio of ads make up their content; who advertisers seek to deliver that content to is shaped by how an ad is targeted by an advertiser. Platforms also have algorithms (such as promoting engagement) and auctions (to maximize the price of reaching particular audiences) that shape who actually sees paid political communications. Algorithms and auctions are beyond the scope of this study; however, we turn here to targeting policies.

As discussed above, while social media platforms have created policies to address content in ads, they have been slower to address potentially racist or politically discriminatory targeting. Even more, while enforcement remains opaque to us, we could find no explicit statements regarding the scrutiny paid to the targeting of historically vulnerable populations.

For example, a number of companies have developed clear policies against targeting people based on sensitive categories (or “personal attributes,” in YouTube’s case) which include race and ethnicity. A number have also specifically limited the targeting options available to political advertisers (in Twitter’s case, targeting restrictions apply to the advocacy organizations that are still permitted to advertise amid a ban on political advertising). For example, Twitter created “sensitive categories” of personal customer data and explicitly states that “sensitive categories” of “race or ethnic origin” (amongst others) may not be targeted by advertisers. Google, similarly, has limited the targeting options available to political advertisers. Political advertisers may not load their own audiences onto the platform, target audiences based on most user data, or target very small geographical locations. Over the past year Facebook rolled out a number of targeting restrictions, including by religion, race and ethnicity, and political affiliation. Reddit bans “discriminatory” targeting. Snapchat does not have advertising policies that address how ads are targeted.

While these companies are going beyond only flagging the content of the ads, under our definition above in failing to distinguish between racial and ethnic groups these blanket policies are color-blind. Preventing political advertisers from targeting people based on race, ethnicity, extremely small geographies, and advertisers’ own lists of people might stop them from sending messages designed to depress turnout in ways that might be allowable under current content rules. That said, such blanket policies might also prevent targeted voter registration and turnout campaigns that deliver highly relevant information to historically under-politically represented populations. This is precisely our logic for race-conscious policies.

Conclusion

It is likely that the failure of platforms to develop more race-conscious policies in the context of institutional politics, and enforce them, stems from both concerns over charges of bias in the development and application of policies and the global scope of these companies, which make any attempt to address specific countries’ racial disparities or racist histories difficult. Definitions of race and ethnicity are socially and politically constructed, and writing rules adequate for many countries with unique histories would necessarily require intricately specific approaches to policy and enforcement to properly address each context of historical race relations.

The clearest area for race-conscious policies has been, not surprisingly, around hate speech. A number of platforms have clearly identified historical patterns of vulnerability and differences in social power. While this is to be applauded, the failure of existing civic integrity policies to address race and ethnicity at all in the United States is surprising given the country’s racial history. Even more, color-blind abstract policies that apply to all racial and ethnic groups - found variously throughout these areas and especially around political ad targeting - likely undermine the stated civic goals of platforms.

When platform policies explicitly mention race and ethnicity, among other things, but fail to distinguish between socially dominant and dominated groups they equate speech directed at or about very differently positioned social groups, preserving color-blindness through the lens of abstract ideals. While there is the clear potential for harm that guides these abstract policies, they also prevent organizations from using advertising to register historically marginalized voters, inform them of their rights at the ballot box, or mobilize them to turnout on election day.

We support an extra scrutiny standard to review content and targeting decisions when they apply to historically vulnerable and marginalized groups, and let stand pro-democratic uses of these platforms. Broadly, platforms should invest in the resources to engage in the extra scrutiny of content that affects historically discriminated-against groups and weed out pro-democratic from anti-democratic content and targeting. Once this content is flagged, platforms should make the call regarding whether it is a pro-democratic use of the platform consistent with their policies and values, or runs counter to them. To truly create race-conscious policies and enforcement would take staff, understanding, expertise, and resources. While costly, we think it is necessary if these platforms are going to live up to their stated civic ideals and embrace democratic processes.

To furnish a few examples of race-conscious approaches:

- Advertising content policies could require additional review for any content relating to historically discriminated against populations in the two weeks before an election.

- Policies could require that any political advertising targeting historically discriminated-against populations undergo extra scrutiny for its content. Advertisers must enter target audiences, for instance, and in the U.S. content targeting Black Americans or people of color more generally could trigger a time delay for additional review.

- Platforms could apply greater scrutiny to accountsthat have a history of disseminating speech that targets racial or ethnic minorities or historically vulnerable populations. This could happen through platforms putting these accounts’ posts on a time delay for expedited review to ensure that content does not violate civic integrity standards.

Social media platforms must account for the United States’ racial history of voter suppression-- and those histories relating to other populations in countries around the world-- in order to treat their users fairly and protect those who historically have been the targets of attempts at political suppression.

Authors