The Global Digital Agenda and the Path Toward a Balanced Future

James Görgen / Oct 3, 2024Eleven years after Edward Snowden’s revelations, Brazil is once again at the epicenter of the digital geopolitical agenda. This time, however, there are objective conditions and a window of opportunity for countries to reshape the future of digital governance and curb the excessive control exerted by a few technology companies and states over global society, writes James Görgen.

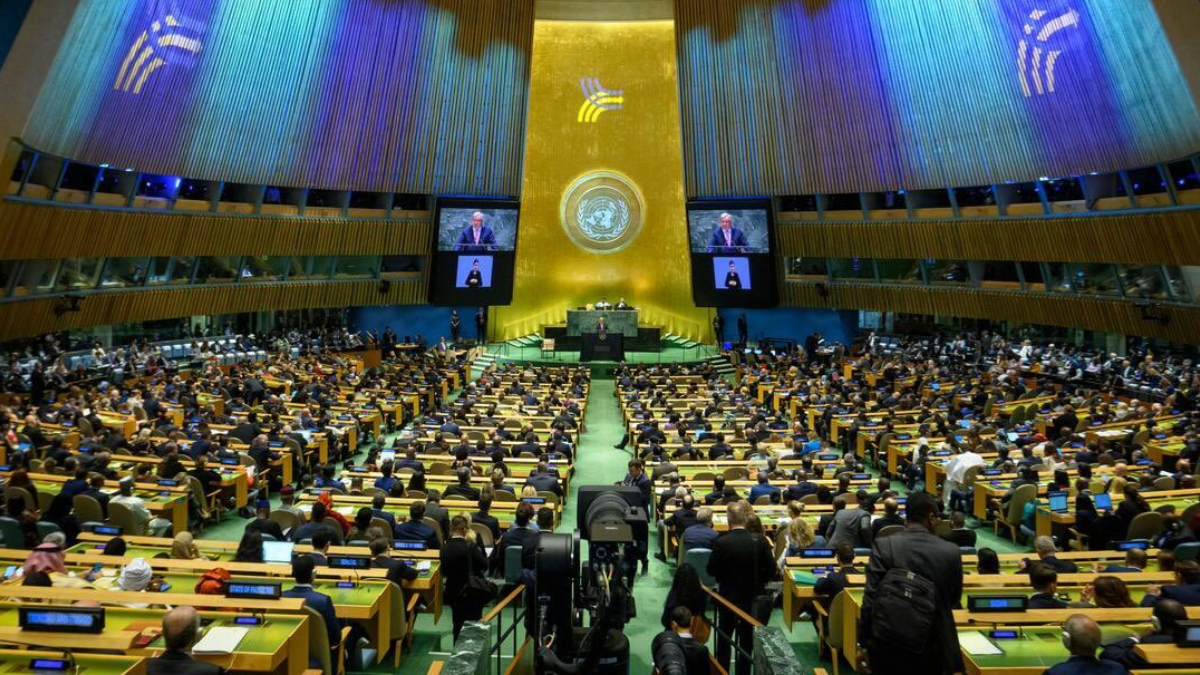

The Global Digital Compact was adopted at the UN General Assembly in New York City on September 23rd, 2024. Source

It is said that history repeats itself: once as tragedy, and again as farce. Eleven years after NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s revelations about the US government's digital espionage on Brazilian political leaders and companies, a new act is unfolding. The same actors, the same plot but — for the first time in 55 years — with an unpredictable outcome. Forget billionaires aiming to politically control developing countries to expand their businesses and access strategic natural resources. The recent case in my country is merely the tip of the iceberg.

Looking under the surface, it is crucial to connect certain dots, and to gather evidence demonstrating that more complex machinery is at work, in which Brazil is one of the most evident laboratories. Looming over all the digital policy crises is a geopolitical arrangement with initiatives that seek to expand the dominance of transnational conglomerates both economically and in terms of the US national security doctrine and its historical unilateral control of the Internet.

Since 2013, however, much has changed, both in terms of the configuration and actions of so-called Big Tech firms, and the reaction sparked by their behavior from national states, businesses, and citizens. This brings us to a perfect storm, not only to foster the re-foundation of the internet but also to end the global hegemony of some economic groups over local digital ecosystems.

Supranational states

The geopolitics of today’s multipolar world has become more defined as nations seek to press forward their own digital agendas at the intersection of economic and security concerns.

In the Snowden era, companies primarily dominated the application layer of the Internet, particularly with global monopolies or duopolies in search engines, social networks, and messaging services. Over the last decade, Big Tech leaders realized that maintaining control of these markets required consolidating and vertically integrating their power across–and controlling without always owning–the entire digital value chain.

Some of these companies expanded their focus to infrastructure—both connectivity and data storage and processing. Today, four American tech giants (Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft) control over 50% of the world's subsea fiber-optic cables and three of them–Amazon, Microsoft and Google–nearly 70% of the global data center and cloud services market. Amazon (Kuiper) and X (Starlink) also have investments in low-orbit satellite constellations to provide internet services to individuals, businesses, and even military corporations in various countries.

Their dominance has been secured by reinforced lobbying in strategic, mostly invisible spaces, such as the capture of organizations that define internet standards and protocols, governance environments; opaque relationships with civil society and academia; and the capture of lawmakers and regulators. This ensured their vertical integration while avoiding regulation through the "immunity" granted by laws like Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA), which treats companies as mere intermediaries that cannot be held liable for most illegal or improper conduct by third parties using their platforms. This concept was incorporated into the Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet, a law passed a year after Snowden's revelations.

This omnipresence in every bit of the digital and computing stack necessary to ensure their dominant position has led Big Tech companies to operate practically as supranational states. They regulate their own – and everyone else’s – markets, induce business processes with their business models, define security policies, monitor the activities of their “inhabitants,” punish improper conduct, invest in R&D, capture research through ties with universities and public research organizations, control a network of start-ups with their venture capital money, acquire shelf innovation, and commercialize their proprietary data. Seen through a certain lens, the primary production of Big Tech companies is governance.

By acting as states with overlapping territories, it seems natural that any movement towards independence or technological self-determination by another state would threaten them, leading to defensive reactions to preserve their markets. And the maneuvers to secure their territory or sphere of influence, like interventionist and non-democratic nations, are varied and can include, at the extreme, co-optation and manipulation of public opinion.

Perfect storm

The counter-reaction generated by this imperialist behavior has been unfolding in various democratic countries across multiple areas simultaneously—even in Big Techs' own birthplace. US public institutions no longer follow the former consensus that these conglomerates should operate without regulatory constraints to achieve global gains. Both the US Department of Justice (DoJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are undertaking antitrust action, aiming to preserve digital markets for new entrants, to prevent the death of innovation due to killer acquisitions, and to protect consumer rights.

This perception also resonates in the judiciary, which has handled significant cases, such as the two accusing Google of monopolistic practices and a recent decision involving TikTok, where Section 230 was tested. Added to this are legislative actions in various states, generating advanced regulations on topics like opt-out, AI, and privacy.

In the UK, investigations into the anti-competitive practices of some Big Tech companies have already resulted in significant decisions regarding their accountability. The focus, once again, is on curbing economic abuses, including recent business arrangement analyses involving foundational AI models.

The European Union is perhaps the most emblematic case of resistance. After more than a decade of crafting a myriad of laws aimed at curbing the advance of digital platforms, protecting personal data, and regulating digital markets, the bloc is collecting some pyrrhic victories. In one sector or another, gatekeepers have been called to answer for abuses committed. Regulations such as the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the Digital Services Act (DSA), the Data Act, and the AI Act have served to rein in the Big Tech firms operating in the region.

A few months ago, the alignment of actions across these three domains led to an unprecedented regulatory antitrust alliance. The US, UK, and the European Commission issued a joint statement not only recognizing that the hegemony of these five companies has caused significant damage to these markets but also that it must be contained.

The European Commission went further, complementing its actions with normative instruments through a digital independence action targeting industrial policy. The report, not endorsed by the Commission, containing measures to enhance competitiveness within the bloc, released by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, recommended specific initiatives for regional development linked to the digital agenda. Perhaps the most important of these is the creation of sovereign cloud services, followed by measures on the development of national AI systems and consolidation of European telecommunications service providers.

Signals that the EU might be shifting its focus on the digital agenda from complex regulations to industrial policy have moved tectonic plates that are acting to make the change a reality. And certain statements demonstrate the relevance of this European movement for the status quo of digital markets and national defense. Both Elon Musk and US vice-presidential candidate J.D. Vance praised Draghi's document. Former President Donald Trump's running mate went further by threatening Europe that his government could withdraw resources from NATO if the bloc insisted on regulating big tech. Now it's time to follow the developments to see if the threat intimidates the European Commission's new sheriff in this area, Finnish Commissioner Henna Virkkunen.

Canada and Australia have also made significant advances in regulating and taxing digital platforms, including for the remuneration of news media organizations, drawing criticism from companies and their controllers, and accusing them of attacking freedom of expression or even engaging in fascist behavior. In a clear signal that it does not intend to remain entirely dependent on big tech infrastructure, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau announced public investments in a Quebec-based company to launch a low-orbit satellite constellation.

On the global fronts of trade and tax policy, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are also arenas for debates that are cornering Big Tech firms. Notably, in 2026, the likely end of the moratorium on the non-imposition of customs duties on electronic transmissions, created in 1998 and enabling Amazon’s rise through the concept of free cross-border data flows, may have a significant impact. Meanwhile, under the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative, a pool of over 100 countries is negotiating a multilateral agreement that includes a clause to impose a global tax on big techs, with revenue shared among signatory countries.

Within the UN system, the first stone was cast with the debates surrounding the Summit of the Future and the Global Digital Compact. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ proposal to create specific structures for the digital agenda in New York has troubled the historical beneficiaries of the current multi-stakeholder Internet governance architecture. For two years, they sought every possible means to weaken the initiative and dilute the document, which enjoys support from various countries and was approved during the UN’s meetings in New York last week.

The Brazilian laboratory

Brazil has been at the forefront of this countermovement. By banning the platform X (formerly Twitter) throughout its territory and seizing funds from both the Musk-owned X and Starlink’s bank accounts to settle outstanding fines, the Brazilian judiciary, like its US counterpart, has shown that it understands the game. Similarly, Brazil's Supreme Court will soon rule on the constitutionality of the Brazilian equivalent to Section 230 of the CDA. This legal and narrative battle coincides with President Lula da Silva’s statements in international forums (such as the G7 Summit, Mercosul Summit, International Labour Organization and, last week, at the UN General Assembly and Summit of the Future), asserting that Brazil has a strategic digital sovereignty project aimed at achieving independence without resorting to isolationism, unlike other states that have structured their digital markets.

After serving as a testbed in the Snowden episode, countries like Brazil have become the ideal laboratory to observe how all of this is unfolding and what the potential outcomes might be. In fact, Brazil is home to an insurgency against Big Tech. As we were for decades in agriculture, we are habitual producers of the commodity most prized in the tech age: data.

Over 80% of Brazil’s population is connected. The country ranks second in social media usage, and second place where users spend the most hours connected every day globally. Brazil is also the continent’s largest economy, with businesses of all sizes undergoing digital transformation, making it the tenth-largest IT services market globally. Initial estimates suggest that Brazil's digital economy accounts for 7% to 10% of GDP, generating nearly R$1 trillion annually.

At the same time, the Brazilian state has developed several public layers of the computing stack from infrastructure to platforms. Four public entities (Serpro, Dataprev, Telebras, and RNP) have fiber-optic networks, a geostationary satellite, and data centers capable of offering cloud services and developing digital solutions. At the upper layer, 150 million users access more than three thousand services through a public platform (GOV.br).

On these grounds, and given this administration’s commitment to developing the country, the Brazilian state is getting ready to lead and steer the digital transition in the country. Brazil New Industry – NIB, the Brazilian Artificial Intelligence Plan – PBIA, national policies for data economy and governance, and public bank credit to companies in the digital economy can be seen as a bundle of policies aimed at coordinating Brazil’s digital economy from the public sector and for the citizens and development. This has provided confidence for President Lula da Silva to begin addressing the need for autonomy for Global South countries in the technology field.

Coincidentally, the country has started to experience reactions from these companies. The most high-profile case involved Elon Musk. But more importantly, there has been a subtle form of harassment building up, as demonstrated by recent allegations made by a former minister and representative related to Amazon and the US intelligence and defense authorities’ interests in the country’s decisions.

The path forward

Returning to the perfect storm, the good news is that our country is not alone in its potential intention to be the swing factor in the blue cold war. Various nations seeking similar self-determination and a reduction in Big Tech dominance—whether from one power or another—are pursuing similar strategies. Beyond those already mentioned, this includes countries like South Africa, Indonesia, South Korea, India, and many others. Some weeks ago we received the good news about a supporting letter for the digital sovereignty national project signed by scholars like Thomas Piketty, Mariana Mazzucatto, Francesca Bria, Cecilia Rikap, Daron Acemoglu, and dozens more.

It is therefore up to some of these democratic nations to take on the responsibility of forming a global alliance that protects states with digital sovereignty projects while also imposing checks on the excessive influence of these supranational entities. More than just protecting human and individual rights—subjects of regulations that have dominated international debates so far—there is a need for a global system to strengthen measures aimed at ensuring autonomy over digital infrastructure, developing culture and democracy on the internet and AI platforms, and maintaining fair and contestable digital markets.

Brazil seems ready to support the global community in this process. While the country does not seek isolation, nor the fragmentation of the internet, it is clear about the need to state that society has reached its limit concerning the negative externalities generated by these conglomerates over the past 20 years, which go far beyond economics and geopolitics. The opportunity is here. It is time to rebuild the digital agenda—so that history does not repeat itself as tragedy.

Authors