The Future is Analog (If You Can Afford It)

Maroussia Lévesque / Aug 23, 2024This post is adapted from the long form paper Analog Privilege, published in the New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy.

Image by Alan Warburton / © BBC / Better Images of AI / Plant / CC-BY 4.0

Analog is back. From no-phone teens to homesteading and the coastal grandmother aesthetic, shunning technology is a new trend that appears to be here to stay. The backlash against anxiety-inducing blue screens signals a yearning for simpler times and also a new split in people’s ability to curate their relationship with technology. Avoiding digital technology is a measure of sophistication and, ultimately, power.

The idea of "analog privilege" describes how people at the apex of the social order secure manual overrides from ill-fitting, mass-produced AI products and services. Instead of dealing with one-size-fits-all AI systems, they mobilize their economic or social capital to get special personalized treatment. In the register of tailor-made clothes and ordering off menu, analog privilege spares elites from the reductive, deterministic and simplistic downsides of AI systems.

Of course, AI systems show great promise in areas suited for probabilistic reasoning such as molecule discovery or weather pattern detection. But they also have a dark side: deployed in high-stakes contexts to replace human analysis, they gloss over nuances and contextual cues, reproduce and amplify bias, and lock people into backwards-looking algorithmic prisons that perniciously constrain future opportunities. These systems are often first tested and deployed on the most vulnerable populations – something the writer and activist Cory Doctorow describes as the “Shitty Technology Adoption Curve.”

Yet as technologies become more pervasive and climb up the social ladder, the ability to opt out correspondingly narrows. Elites maintain a moat against broadly applicable AI systems. They engage with AI on their own terms – for example, using expensive services powered by facial recognition to clear border checkpoints faster, which the geographer and professor of politics Matthew Spake describes as the biopolitical production of a transnational business class citizenship, or finding analog workarounds to shield themselves from punitive systems like those detecting child mistreatment. Put simply, analog privilege preserves one’s ability to be seen amidst all the complexity and contradictions of human existence.

To understand analog privilege in action, let’s take a look at how elites bypass workplace productivity monitoring and automated content moderation.

Nanomanaging Employees

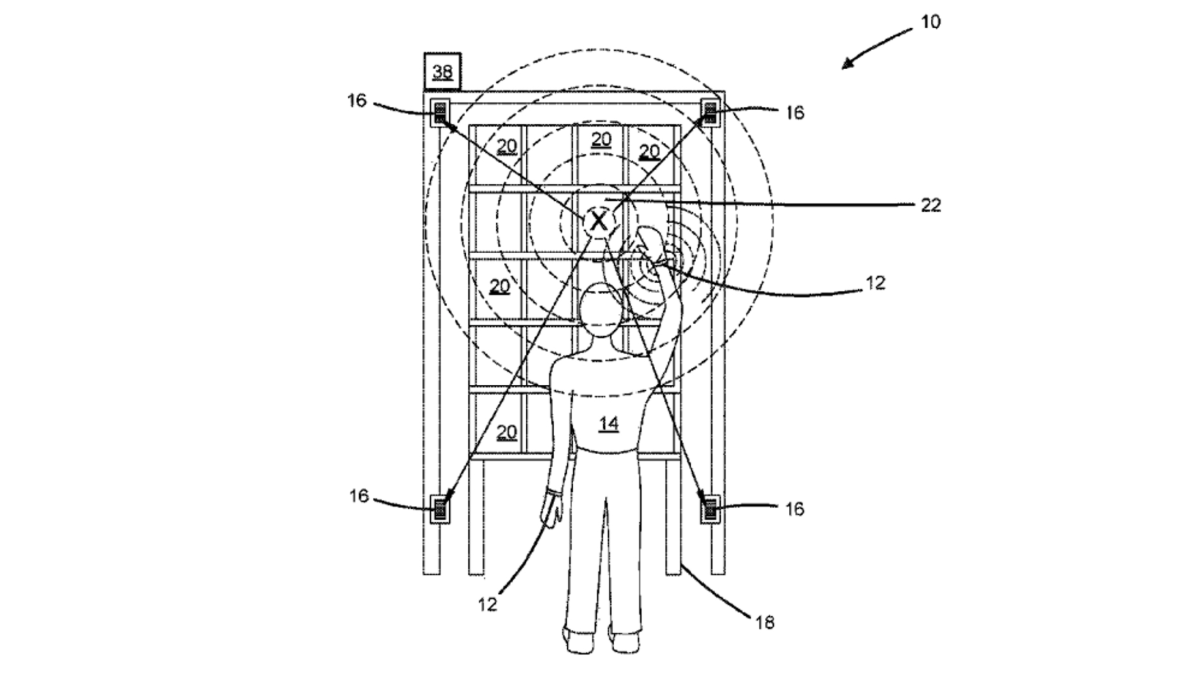

From warehouses to law firms, AI systems enable employers to watch workers’ every move. Warehouses are considering smart wristbands that vibrate to guide workers, literally taking them by the hand to guide their every move. The technology could provide positive and negative feedback in terms of frequency, pulse and amplitude, suggesting that unpleasant haptic feedback akin to a slap on the wrist is on the table. Though these smart wristbands have yet to be implemented, they illustrate the granular, constant, and invasive control AI enables over workers’ bodies.

Ultrasonic bracelet and receiver for detecting position in 2D plane. Source: Patent US9881276B2

In her fascinating account of the data-driven transformation of the trucking industry, sociologist Karen Levy describes a flotilla of digital monitors curtailing drivers’ autonomy and imposing rigid, acontextual constraints. Nominally for safety purposes, AI-powered smart cameras purport to detect yawning and distraction, and sensors flag tires spinning or abrupt acceleration. In the long-haul trucking industry, electronic logging devices monitor time on the road to ensure compliance with regulations capping driving time. These devices further track fuel efficiency, speed, idling time, geolocation, lane departure, braking and acceleration patterns.

AI-powered surveillance is also coming to white-collar workplaces. Knowledge workers – people who think for a living – typically enjoy some latitude regarding the execution of abstract, complex, or creative tasks. But those jobs are in the throes of a paradigm shift from relative autonomy to technology-powered productivity monitoring. Many companies now require employers to submit to remote monitoring in return for post-pandemic flexible remote or hybrid arrangements. This new breed of remote productivity monitoring tracks minute details like keyboard strokes and mouse movement, and even eye movements. Workers must constantly stare at a camera tracking their focus with facial recognition. Ironically, self-aware workers have to babysit wonky systems instead of engaging in deep thinking to get actual work done.

Workplace monitoring is gradually climbing up the social ladder in accordance with Doctorow’s curve, but there are good reasons to believe it will stop short of the highest echelons of CEOs and other high-level executives. Those positions typically entail a significant zone of autonomy, and performance is evaluated along much more subjective factors like ‘leadership’. By virtue of more abstract and subjective performance benchmarks, the upper echelons of the workplace are likely to remain analog, tailoring performance evaluation to the specific context at hand.

Analog privilege begins before high-ranking employees even start working, at the hiring stage. Recruitment likely occurs through headhunting and personalized contacts, as opposed to applicant tracking systems automatically sorting out through resumes. The vast majority of people have to jump automated one-size-fits all hoops just to get into the door, whereas candidates for positions at the highest echelons are ushered through a discretionary and flexible process. Though automated applicant tracking systems purport to smoke out latent bias (say against unconscious racial bias disadvantaging candidates with an ‘ethnic’ sounding name), in practice they also disqualify people on technicalities without ever telling them why. Overall, AI in the workplace is a good example of analog privilege because it preserves flexibility for higher-ranking employees to avoid simplistic and invasive hiring and monitoring AI systems.

Whitelisted VIP Social Media Users

Content moderation is a numbers game. Individual human review is unrealistic given the volume of content users share, so platforms turn to probabilistic guesstimates to enforce applicable laws and content policies. For 99% of users, machine learning algorithms moderate content. Even when (overworked, traumatized, underpaid) human moderators are involved, they only spend 30-150 seconds on each post – mechanically clearing their cue in a way that hardly leaves space for contextual considerations. These fuzzy guesstimates lack nuance and texture. For example, Instagram confused content about Islam’s third-holiest mosque with a terrorist entity bearing a similar name. The backwards-looking methodology of detection algorithms also limits their performance, as they can only predict future violations based on past ones. As online speech morphs quickly to avoid detection, new forms of violations will always be a step ahead of detection algorithms – such as when right-wing extremists changed the war cry “selva” to “selma,” during the 2023 attempted coup in Brasilia.

In light of AI’s limitations, platforms give prominent users special analog treatment to avoid the mistakes of crude automated content moderation. Meta’s cross-check program adds up to four layers of human review for content violation detection to shield high-profile users from inadvertent enforcement. For a fraction of one percent of users, the platform dedicates special human reviewers to tailor moderation decisions to each individual context. Moreover, the content stays up pending review. Privately, Meta employees worried that this special treatment conferred an additional advantage of “innocent until proven guilty” in internal discussions revealed by whistleblower Frances Haugen. VIP users could share content until the final decision, contrary to regular users who are subject to immediate AI-powered takedowns for policy violations. Because fresh content gets more views, this aspect of analog privilege allows prominent users to distribute content at peak virality.

The cross-check program exemplifies analog privilege because its VIP enrollees get special analog review instead of coarse AI-powered filters. Of note, the platform didn’t notify high-profile users about the perks of the special cross-check program. Analog privilege thus naturalizes special treatment, keeping beneficiaries blissfully unaware of their advantages.

Bridging the Automation Divide

AI systems constrain our ability to beat the odds, flip the script, or start over. As they increasingly mediate important aspects of our lives – what college one attends, whether a parent has to repel state suspicions of child mistreatment, or even whether an accused gets bail or parole – the ability to secure a manual override becomes ever more advantageous. In many cases, elites secure cheat codes to avoid the downsides of AI systems and benefit from preferential analog treatment instead.

This kind of double standard creates an automation divide: coarse automation for almost everyone versus preferential analog treatment for the select few. This fault line between people subject to and exempt from automation fits and feeds into a broader resentment-fueled populism, eroding the already strained social fabric. Analog privilege is nefarious because it contributes to resentment against elites benefitting from exemptions and erodes the ‘death and taxes’ egalitarian ideal of Benjamin Franklin. Just as the uber-rich turn to cryogenic body preservation and offshore tax havens, they now bypass widely applicable AI systems.

Leveling the playing field

There are many ways to reduce and perhaps even eradicate analog privilege. A right to be an exception can grant manual overrides based on merit instead of social or economic status. Since analog privilege and automated precarity are two sides of the same coin, protecting people against some detrimental AI systems correspondingly reduces analog privilege. To that end, the EU AI Act’s ban on unacceptably high-risk systems is directionally sound. But high-level AI laws alone won’t cut it: the technical community is also crucial to improving intelligibility so people subject to AI systems can actually understand and contest decisions.

Ultimately, looking at analog privilege and the detrimental effects of AI systems side by side fosters a better understanding of AI’s social impacts. Zooming out from AI harms and contrasting them with corresponding analog privileges makes legible a subtle permutation of longstanding patterns of exceptionalism. More importantly, putting the spotlight on privilege provides a valuable opportunity to interrupt unearned advantages and replace them with equitable, reasoned approaches to determining who should be subject to or exempt from AI systems.

Authors