The Far Right’s War on Content Moderation Comes to Europe

Dean Jackson, Berin Szóka / Feb 11, 2025Tech Policy Press Contributing Editor Dean Jackson and TechFreedom President Berin Szóka ask, will Europe face US demands on social media regulation with defiant resistance, or will the continent’s growing anti-regulatory mood and vocal right-wing prevail?

A hard rain falls on Brussels. Shutterstock

On January 7, Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that his company would significantly reduce moderation of lawful but awful content on Facebook, Instagram, Threads, and WhatsApp. Meta is clearly desperate to avoid the wrath of the new administration, which appears determined to finish what it started in 2020: “jawboning” tech companies to cease moderating content in ways that MAGA Republicans think hurt them. In some ways, this is understandable: Meta has much to lose. But many criticized the company for surrendering to President Donald Trump after years of attacks on what he and the MAGA movement decry as politically biased “censorship.” Others downplayed the move; Politico called it mere “marketing to the power structure.”

Both sides are, at best, only half-correct. The MAGA war on content moderation is rapidly becoming a larger geopolitical struggle against social media regulation. Elon Musk is already part of that struggle. Zuckerberg isn’t surrendering or merely marketing; he’s making a strategic play for partnership with the incoming administration in the global battle over how online platforms and speech are governed. Most coverage of Meta’s changes focused on the company abandoning fact-checking. Yet far more consequentially, Meta will also cut back on moderation of hate speech, misinformation, and the like—creating very real risks of the kind of violence that erupted at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. But the most important part of Zuckerberg’s announcement is that Meta will “work with President Trump to push back on governments around the world” because “they’re going after American companies and pushing to censor more… Europe has an ever-increasing number of laws, institutionalizing censorship, and making it difficult to build anything innovative there.”

Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA) entered full force just a year ago, on February 17, 2024. It gives the European Commission broad discretion to interpret the law’s key terms, notably whether large tech companies are doing enough to mitigate “systemic risks” caused by their services. The first DSA enforcement action involves the adequacy of X’s reliance on “Community Notes” instead of fact-checking misinformation; the Commission has not yet weighed in on whether Community Notes will be sufficient to meet X’s DSA compliance obligations but is expected to soon.

But now, Europe and America are in the early stages of a transatlantic digital cold war. Zuckerberg may believe victory in that war will free him from what he sees as costly and burdensome regulation. What it will not buy him is freedom writ large: the Trump administration will hold leverage over Meta as long as it remains in power, and the MAGA right is unlikely to be sated by just one concession. “Anticipatory obedience” is always dangerous, as historian Timothy Snyder explains in his book On Tyranny:

Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.

Other European competition, privacy, and AI laws could also require tech companies to make fundamental changes to their services. All these laws carry the threat of large fines. But will the European Commission actually enforce them under intense pressure from the Trump administration? Will Europe face US demands with defiant resistance or will the continent’s growing anti-regulatory mood and vocal right wing prevail? Experts believe it is too early to write obituaries for the EU’s digital regulatory agenda, but predict existential struggles ahead.

What Meta Announced

To situate Zuckerberg’s announcement in the context of this struggle, it’s important first to interpret the January 7 announcement. That day, Meta promised three major changes. First, as on X, instead of relying on outside experts to apply fact-checking labels, Meta will rely on users to decide which content merits “Community Notes” and what those notes should say. This was the most widely reported of the three changes but the least consequential. Second, Meta also said it would cease reducing the visibility of content labeled as misinformation. And third, it loosened restrictions on a variety of content.

While these changes will start in the US, Meta Chief Global Affairs Officer Joel Kaplan says the company will eventually roll out similar changes in the EU. If these changes do roll out in Europe, they are likely to invite regulatory scrutiny. The DSA requires Meta to (1) assess the risk of various harms stemming from its policies and services, and (2) to “put in place reasonable, proportionate and effective mitigation measures.” It is unclear that Community Notes would meet these requirements, to say nothing of the other changes.

These changes seem primarily designed to placate MAGA Republicans, who have seethed about fact-checking since Facebook started doing it in 2016. In 2019, they browbeat the company into giving up on fact-checking politicians’ ads. In early 2020, fact-checking became a central front in the Culture War after Twitter began attaching labels to President Trump’s tweets containing patent lies about the upcoming election being “rigged” against him. Reportedly enraged, President Trump promptly issued an “Executive Order on Preventing Online Censorship,” promising to use the full weight of the federal government to defend what he called “free speech.” His administration proposed various ways of cracking down on content moderation but lacked both time and loyalists willing to implement its ideas.

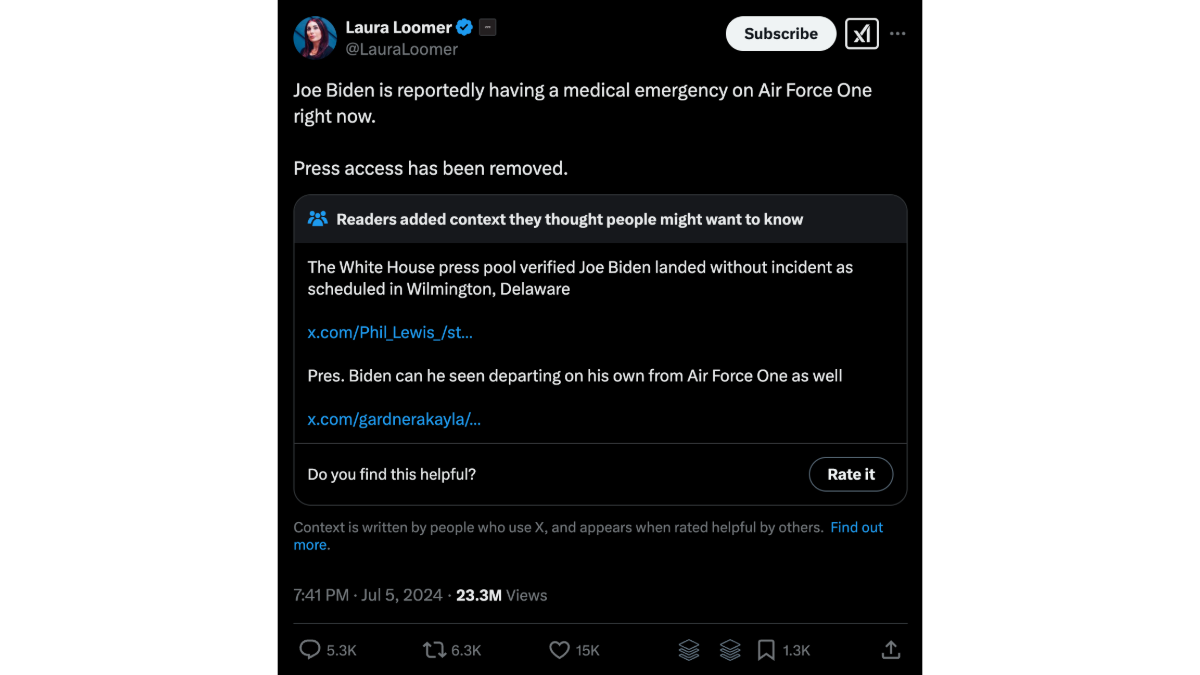

In 2021, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey tried to get his company out of the fact-checking business, just as Zuckerberg is doing now. Twitter launched “Community Notes,” which look like this:

Source: X

When Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022 and renamed it X, he fired nearly the entire trust and safety staff, making Community Notes X’s primary way of dealing with lawful but awful content.

Zuckerberg wants to imitate X, where he says, “We’ve seen this approach work.” It certainly “works” in the sense of avoiding Republican ire, but many researchers doubt its overall utility (as to be fair, they raise doubts about fact-checking). “Despite a dedicated group of X users producing accurate, well-sourced notes, a significant portion never reaches public view,” concluded a 2024 report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, which found that “74% of accurate Community Notes on US election misinformation never get shown to users.” This allowed 209 misleading posts to get 2.2 billion views. Like X, Meta “will require agreement between people with a range of perspectives to help prevent biased ratings.” But, as CCDH explains, “on polarizing issues, that consensus is rarely reached. As a result, Community Notes fail precisely where they are needed most.” (Google has hinted it will also replace fact-check labels with a community notes system but doesn’t appear to be making other changes at this time)

It’s not clear whether Meta intends anything different. Meta might set the bar for assessing “agreement” lower than X has so that more false posts would have Community Notes. Community Notes might offer benefits in speed and scalability that help offset the loss of professional fact-checkers. But ultimately, there’s no engineering solution for what is ultimately a people problem. To call Meta’s user base a “community” implies that it has something fundamental in “common,” but increasingly, the Internet more resembles Mad Max than any New England town meeting.

Certainly, it isn’t just MAGA zealots who resent having their content taken down or its visibility reduced. The automated systems Meta uses to identify and moderate toxic content are inherently imperfect. “Content moderation at scale is impossible to do well,” as TechDirt’s Mike Masnick famously put it: “It will always end up frustrating a large segment of the population and will always fail to accurately represent the ‘proper’ level of moderation to anyone.” But Meta doesn’t need to moderate all users equally; as David Lazer and Sandra González-Bailón note, “supersharers” are the primary means by which mis- and disinformation spread on Meta’s platforms, and Meta could focus its efforts on that much smaller subset of accounts. This would be no more or less an editorial decision than deciding to moderate less actively.

Zuckerberg has made a different editorial choice altogether. Meta, he says, has “[gotten] rid of a number of restrictions on topics like immigration, gender identity, and gender that are the subject of frequent political discourse and debate.” Community Notes will do little, if anything, to decrease the risk of violence created by conspiracy theories and dehumanizing speech. Should Americans be able to talk about immigration? Of course. Does Meta have a moral obligation to allow users to refer to transgender people by the dehumanizing pronoun “it?” Of course not.

The View from Europe

If the EU Commission were to find Meta out of compliance with the DSA, the company could pay a heavy cost. Penalties for DSA noncompliance are high—as much as six percent of worldwide turnover. Kate Klonick, associate professor of law at St. John’s University, suggested in an interview that opposition to the DSA on speech grounds could be a “pretext for preventing catastrophic fines.” This aligns with Meta executive Joel Kaplan’s recent declaration that the company considers regulatory fines a form of “tax or tariff” against US companies.

But as Stanford legal scholar Daphne Keller noted to us, the DSA is just one of several laws serving as the pillars of Europe’s regulatory vision: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Artificial Intelligence Act are also factors. Since the GDPR took effect in 2018, there have been 2,000 enforcement actions, including billions of euros in fines for Meta. Mark Scott, a fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (and, as announced this week, also a Contributing Editor at Tech Policy Press), told us that the DMA — which seeks to break monopoly power and promote competition — could be an even “more existential risk in the short term,” because it rests on preexisting and well-understood antitrust concepts.

It is possible Zuckerberg’s remarks were meant only to appease a domestic audience of one man: President Donald Trump. Even if so, Keller says that they “have set balls in motion elsewhere… Meta has fired shots at these powerful regulators in a way that seems deeply irrational to a lot of people.”

It is more likely that, facing not only enormous fines but fundamental changes to Meta’s business model, Zuckerberg has entered what Scott called an “alliance of interests” with the Trump administration and the digital far right. His rhetoric aligns with Trump’s own in his recent executive order on “censorship,” Vice President JD Vance’s threat to pull US support for NATO over enforcement of the DSA, and the rhetoric of right-wing commentators. Some tech executives, notably Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, are more explicitly allied with Trump than Zuckerberg. Consider Musk’s threats against the EU:

For 80 years, Americans have been made to spend trillions of dollars to ‘protect democracy’ in Europe. Even now, Europe is utterly dependent on America for its own security. The hundreds of billions of dollars we’ve spent in Ukraine have all been to protect Europeans… If all this is going to happen, then at a minimum, Europe should actually be FREE — with real free speech and real elections.

In other words, Europe should scrap the DSA entirely.

European observers are already warning about the Trump Administration’s efforts to strong-arm European regulators into easing up on big tech during tariff negotiations or discussions about military aid to Ukraine. “Over the next four years, Europe’s digital rules, in particular, will be associated with wider trade talks because that’s how politics works,” Scott told us. Exactly how that plays out is anyone’s guess. “It’s difficult to predict what Trump will prioritize or what the incoming administration’s international tech policy will be. Like anything in Trump world,” said Keller. “It’s Calvinball.”

Will the EU make a stand for digital regulation? Maybe. Privately, many in Brussels suspect the Commission will prioritize avoiding aggravating Trump. “While the EU Commission cannot backpedal on investigations into US tech companies already in process,” Scott explained, “in a quid pro quo world, they may slow-walk new ones.”

Will Europe Fold?

If Zuckerberg’s strategy works, if the European Commission relents on enforcing the DSA and European competition laws against Meta, it will be, in part, because of the vagueness of the DSA itself, the continuing ascendance of Europe’s far right, and the military and economic weakness of Europe.

The vagueness of the DSA leaves it open to critique from those concerned about its abuse at the expense of free expression. That potential is real, but more relevant to the far right’s widening war on content moderation is that it creates openings for bad-faith critiques. It allows political actors with ulterior motives to seize on genuine policy disagreements to “work the refs” by overly dramatizing minor transgressions and wholly fabricating major ones. Even advocates for the law concede its vagueness: as Martin Husovec, Professor at the London School of Economics, explains, “the adoption of the risk-based approach to digital services tries to make the law more future-proof. But inevitably, it also makes the law very vague.” Husovec ultimately concludes that “worries that the Commission inevitably becomes a Ministry of Truth are misplaced” because “the Commission must stick to one important red line – it cannot invent new binding content rules.” But he also acknowledges that the law is not impervious to abuse—as one of our organizations led others in warning.

Even if Husovec is right that European courts would, ultimately, block the Commission from making good on such threats, uncertainty about the law and the threat of enormous penalties make the DSA’s risk mitigation provisions a ready tool for “jawboning” tech companies into “censoring” content in ways that aren’t consistent with European free expression law, as many accuse former EU Commissioner Thierry Breton of having done. Breton’s threat was more abstract and far-reaching than the far right’s concrete attacks on academic freedom and liberalism more generally, but fairly or not, the bar is higher for regulators than demagogues. Missteps create opportunities that the far right will not hesitate to exploit.

One component of the DSA, its mechanism for deputizing civil society organizations as “trusted flaggers” of illegal content online, has already come under attack. The first German organization to be designated a trusted flagger, an anti-hate-speech nonprofit called REspect, was accused of “censorship” and received searing criticism from right-wing German media, much of which made conspicuous mention of its directors’ Islamic faith. America’s digital Culture War, it seems, has already come to Europe.

Politically, Scott noted, von der Leyen seems less “gung ho” about tech issues than in her first term, perhaps partly because of the continent’s rightward political winds. “She used to rely on Macron for support,” he explained, “but now Macron has to find his footing after the last EU parliamentary elections and the French parliamentary elections, in which the right made major gains. There has been an overall right-lean in Europe, and that means von der Leyen is now more reliant on someone like Meloni in Italy.”

The possibility that the far right may gain ground in the February 23 German federal elections), in another French snap election this summer, or in France’s next presidential election (scheduled for 2027) is also a complicating factor for the DSA’s future. That fear is very real to French journalist and press freedom advocate Elodie Vialle, who said she sees the far right’s emphasis on national sovereignty as at odds with its reliance on US tech giants for political messaging and reach: “Censorship claims are how the far right squares the circle of sovereignty and dependence on US corporate giants.” She thinks “regulation is actually a way to avoid censorship, to avoid banning platforms,” that is, to change how platforms handle content rather than banning them entirely, the way the US banned TikTok.

Europe is also vulnerable to American bullying over platform regulation because of its increasingly obvious military and economic weakness. Europe has long depended on the US for its security. Here, it suffices to note that what makes it so difficult for the European Union to resist Trump’s bullying over NATO is that he’s not wrong: most European countries do need to spend much more on their own defense.

Europe’s economic weakness is more closely related to the Commission’s potential hesitation to enforce the DSA. Daphne Keller told us that, in this tenuous moment for the continent, recently re-elected EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is likely to prioritize “Europe's economy and unity” over other issues. Kate Klonick explains that some think “the DSA and DMA were never really principled actions, but rather an effort to create a new industry of compliance and to generate revenue based on fines. At the same time, Europe needs US defense spending more than ever and is struggling economically.” From that perspective, striking a deal to relax tech regulation makes sense, even if von der Leyen’s ultimate posture is uncertain.

The economic rationale to strike a deal becomes even stronger when considering the findings of the “Draghi report,” commissioned by the EU to explore ways of boosting Europe’s economic competitiveness. Buried in that three-hundred-page analysis is this long-overdue wake-up call: “The EU’s regulatory stance towards tech companies hampers innovation.” The report says what many have long acknowledged, if only in private: “Regulatory barriers to scaling up are particularly onerous in the tech sector, especially for young companies.” This notion has reshaped the zeitgeist among EU policymakers. “You can’t overestimate the impact of the Draghi report, said Mark Scott. “The winds have changed in Brussels.” Mozilla’s Claire Pershan also sees the report as game-changing. “I’m finding myself having to explain why any regulation at all is good… regulation can be good for people and for businesses,” she explained, citing benefits like rules against anti-competitive practices, uniform technical standards, and regulatory harmony across the EU’s member states. “It’s not tech rules that have prevented European tech startups from emerging,” she argued, pointing to other recommendations about creating a more unified European capital market and improving procurement rules.

The Case for European Backbone

Even if the far right were to gain power in France or elsewhere, Keller believes that Europe’s professional bureaucracy will give some degree of inertia to the DSA and other EU regulation. Either way, Rose Jackson, former director of the Digital Forensic Research Lab’s Democracy + Tech initiative, thinks the European right’s backlash against the DSA should have been easy to predict. “There was always going to be a reckoning,” she argued, because “the DSA is technocratic, but disinformation is not.” If, as Jackson fears, “every conversation between the US government and the EU is going to be about the EU suppressing conservatives everywhere,” will the European Commission stand firm in enforcing European laws, especially the DSA?

“There is definitely a sense of isolation,” said Pershan, and a “real possibility that Von der Leyen pumps the brakes. I think the Commission won’t fold, but the critical period is now.” If they do fold, she warned it would be “worse than having done nothing… Europe spent the last five years designing sophisticated tech regulation. If folding is the result of all that work, what is the incentive to continue?” Pershan and others see concerns about European sovereignty as a strong counter to the MAGA-led effort to subvert EU regulation. “At the end of the day, it’s about sovereignty. EU regulation is also a way to exist from a digital perspective. We don’t really have alternative platforms that can today compete with big tech so far,” said Vialle.

Disagreements about European sovereignty were on full display in a debate of the European Parliament on January 21. Lawmakers on the center and left argued, variously, that Europe cannot allow its policies to be determined by Donald Trump and Elon Musk, that American businesses will suffer if a trade war restricts their access to European markets, and that the issue at stake in the DSA debate was not free expression but sovereignty: the right of Europe to enforce its laws against hate speech, election interference and so on. Will European policymakers be willing to enforce their own laws, just as Brazil’s courts have been willing to enforce that country’s election misinformation law? “Europe must apply the sanctions [authorized by the DSA] on X,” said one speaker. “What is the point of adopting laws in this parliament if the Commission doesn’t enforce them?” Thus far, the Commission has pondered only the limited step of activating its “anti-coercion instrument” in response to Trump’s tariffs on Europe, which could involve suspending American tech companies’ intellectual property rights in Europe.

EU Commission President von der Leyen hit on some of these themes in a speech at Davos. Speaking on coming trade negotiations with the United States, she pledged that Europe would be “pragmatic, but… will always stand by [its] principles to protect our interests and uphold our values.” However, some European leaders feel there is no clear narrative on how digital regulation improves the economy or the lives of Europeans — or what “European values” really mean. As von der Leyen weighs Europe’s commitment to digital regulation against its economic prospects, international challenges, and internal politics, she may struggle to articulate the value of digital regulation to the broader public.

There is a strong constituency for digital safety on the European center and left. For instance, at Davos, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez said social media companies should be held accountable for “poisoning society.” Clearly, many European politicians are not ready to cede the regulatory battlefield to the far right on either side of the Atlantic. Digital rights groups sent a statement to the EU Commission emphasizing the value of digital regulation for “shielding our democracies against foreign interference, for creating opportunities for European innovators, for preserving media pluralism, and limiting the dangerous political and market power that Big Tech corporations hold today,” and warned that Europe must not be bullied by the likes of Musk and Trump.” Or, as Rose Jackson put it: “Imagine being told your country can’t enforce online child safety rules because of what Musk and Trump are doing… That would be a compelling argument [for digital regulation].”

The issue of election disinformation is similarly high-stakes and high-salience. In defense of digital regulation, European leaders might also note that electoral interference and political manipulation by foreign states and ideologically motivated American platform owners are exactly the kinds of “systemic risks” to “civic discourse and electoral processes” that the DSA is supposed to address. Such arguments might resonate with both voters and politicians in Europe, where Elon Musk has cultivated relationships with far-right parties such as the Alternative for Germany. European leaders might similarly label Musk’s growing influence a form of foreign interference as part of their argument for platform accountability and transparency.

Overall, Mark Scott told us, “It is too early to call the demise of Europe’s digital rules. We’re not there yet.” But given von der Leyen’s conflicting priorities, the political debates around regulation in Europe, and the possibility of serious US pressure, advocates for regulation are nervous. Some observers tip into outright pessimism, though they are mostly unwilling to call the match just yet. Kate Klonick thinks “Europe has lost… but the puzzle pieces are revealing themselves, and I don’t think we have them all yet.”

What we can say for sure is that Europe is becoming a major part of the far-right’s war on content moderation. Battlelines have been drawn, forces are mustering, and with the Trump administration threatening imminent tariffs against the European Union, the first salvos are about to fire. The prospect of Brussels waving the white flag has tech policy watchers holding their breath.

Stay tuned for more dispatches from the frontlines — in both Washington and Brussels.

Update March 14, 2025: This piece has been edited to adjust a characterization of a quote attributed to Kate Klonick to more accurately represent her views.

Authors