The DOJ’s Google Search Case – What Next?

Sumit Sharma / Aug 16, 2024

Google offices in New York City. Shutterstock

In his decision on August 5, US District Judge Amit Mehta finds that Google has a monopoly in general search and general search text advertising, and that it illegally maintains this monopoly. Google is expected to appeal the decision. It is unclear as yet if Judge Mehta will allow this appeal before or after the remedy phase of the case. An appeal before the remedy phase of the case will delay the subsequent decision on remedies.

An appeal premised on the idea that general search and the related general search text advertising are not relevant markets is unlikely to succeed in my view. The evidence presented during the trial shows that specialized vertical providers like Amazon and social media platforms like Facebook use different inputs, serve different purposes, and their use is often complementary to general search services like Google (see pages 50-57 and 140-146 of the decision).

In the market for general search services, Google does not dispute that it has an 89.2% share of the market by query volume, and as the decision notes Google’s dominant market share has been persistent at over 80% since 2009 (pages 156-157). This dominant general search market share is mirrored in Google’s share of general search text advertising. Advertisers use general search engine market shares to decide how much their general search text advertising budget to allocate to Google – around 90% according to the evidence presented during the trial (pages 79,156).

Expect an appeal to focus on distribution contracts

The court finds that “It is Google’s status as a monopolist that makes its distribution contracts exclusionary, even if the same conduct did not have that effect when Google first began employing it.” (page 203). These exclusive distribution contracts set Google as the default search engine on three main search distribution channels: Apple’s Mac desktops and iPhones; Android phones; and other browsers like Mozilla, Samsung Internet, and Opera.

It is the legality or otherwise of these distribution contracts as a way for Google to maintain its monopoly that is likely to be the main thrust of Google’s appeal, as Kent Walker, Google’s President of Global Affairs, seems to suggest in his statement on the decision.

The exclusionary effects of these distribution agreements are clear. The court finds that Google’s exclusive distribution agreements foreclose 50% of the general search service market by query volume (page 222), that this exclusion is for a long duration – for example Google’s exclusive distribution agreement with Apple covering 28% of all US general search queries could be extended until 2031 (pages 25,101), and that no other company could bid for and win these contracts (page 225).

This means, as the court finds, that potential general search competitors like Neeva, Bing, and DuckDuckGo are not able to grow their market share to be effective competitors and other innovative services like Branch’s search engine for applications never get off the ground. This is because consumers seldom change defaults. For example, only 5.1% of all search queries on iOS devices went to a rival general search engine through a non-default access point not covered by Google’s distribution agreement (page 209).

As a result, the majority of consumers never get to experience alternatives to Google search. This means they have no way of knowing whether these alternatives are satisfactory in terms of the quality of the search results and whether they might provide better value in terms of innovative add-on features like local business answers, curated news results, privacy protective search, fewer spam results etc. This loss of choice and potential innovation is a consumer harm.

The court also finds that the same exclusive distribution agreements “substantially contribute to maintaining its monopoly in the general search text advertising market, violating Section 2 of the Sherman Act,” and that Google exploits its market power in general search text advertising by charging supracompetitive prices (pages 267 and 259, respectively).

On the other hand, in my reading, the role of scale economies as an entry barrier and a deciding factor in hindering the growth of smaller competitors remains unclear. The court notes that 13 months of user data acquired by Google is equivalent to over 17 years of data on Bing (page 37) but also that at its current scale Bing search quality is comparable to Google’s on desktops (page 46). Neeva was also able in a few years to build a web index and develop a ranking model relying heavily on artificial intelligence technology. It used this to generate its own search results for about 60% of its queries and used syndicated results from Bing for the remaining 40% (page 30).

Potential remedies

Assuming the decision largely stands after any appeals then what could appropriate remedies look like?

Any such remedies would not only need to stop the illegal exclusionary distribution contracts but also consider further remedies that would restore competition to the affected markets while avoiding unintended adverse effects on consumers.

Equally important is that the remedies are easily implementable and monitored given available resources and expertise. As Judge Mehta writes in the decision, while the court has learnt a lot about Google, it is ill suited to act as central planner or get involved in Google’s day to day operations (pages 268–269).

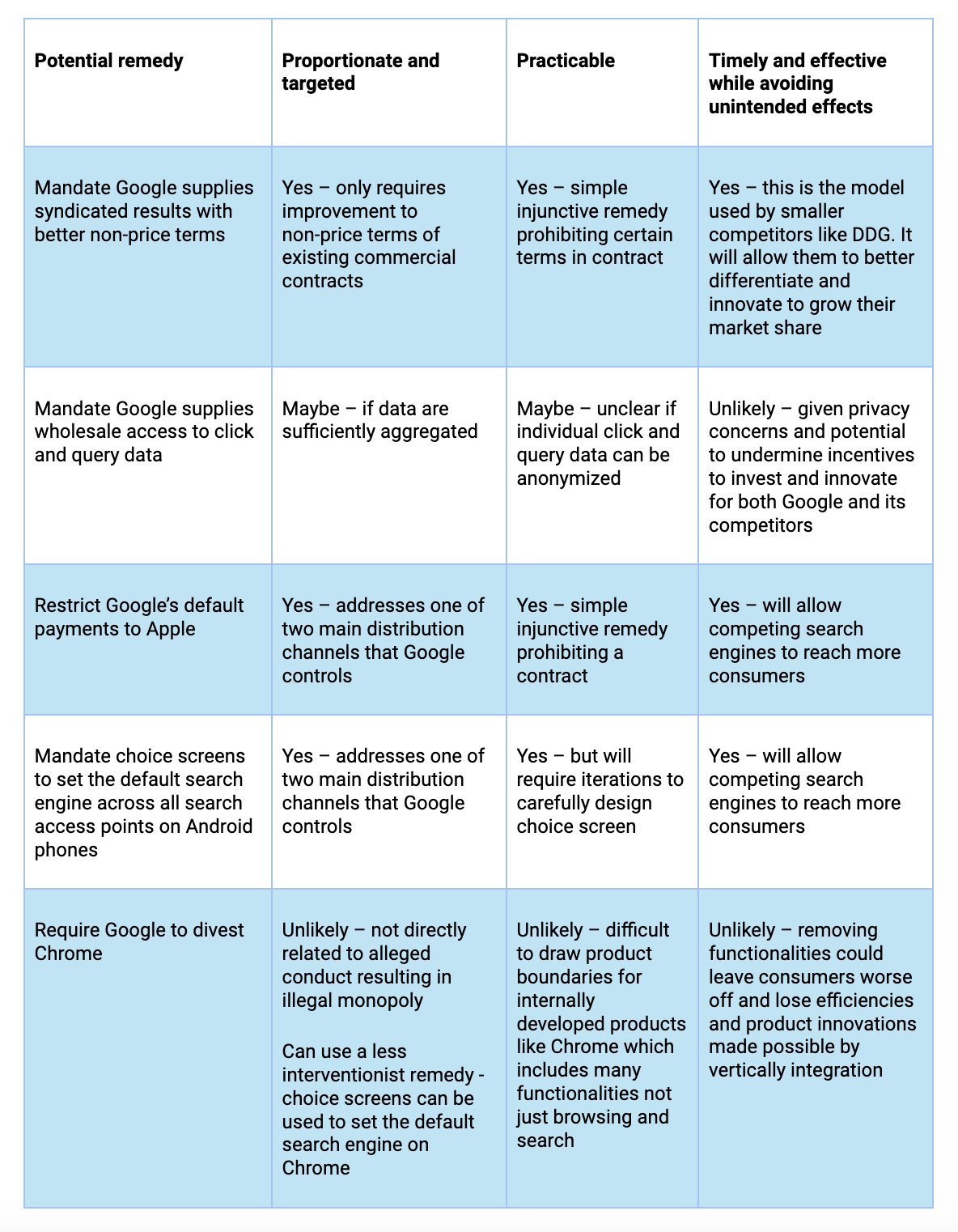

In a paper in February 2024, I analyzed five potential remedies in detail based on these criteria. My conclusions are reproduced and summarized in the table below. The full analysis is available here.

Table: Sumit Sharma

Based on this analysis, in my view a combination of:

- restricting Google from making payments to Apple to be the default search engine on any search access point on Apple devices; and

- mandating choice screens for Android phones covering all search access points including Chrome

would be appropriate to address the impact of defaults on consumer choice and the consequent exclusionary effects on Google’s distribution contracts.

But this is unlikely to be enough. In addition:

- Google should be required to supply syndication contracts with improved terms and conditions which do not restrict the syndicators’ ability to innovate, differentiate, and develop a unique offering.

This would benefit consumers by enabling syndication partners to experiment more freely with different search and add-on features leading to more choice and innovation for consumers.

I note that for a potential competitor to succeed it will need to differentiate itself from Google search in some way. These remedies leave room for innovation and differentiation beyond the ranked organic search results (blue links) that Google would supply under its syndication contract. For example, search engines could differentiate themselves in how they incorporate developing technologies like generative AI and large language models, and how they choose to present additional features such as maps, local business answers, news, images, videos, products/shopping, sports scores, weather, airplane flight information, etc.

The time to act is yesterday

As a final thought, any delay in implementing remedies would benefit the status quo and allow Google to adapt leisurely and still allow it to position itself as a key player in whatever comes next. The need for remedies sooner rather than later seems particularly important given we seem to be at a technological inflection point with the development of generative AI models, which are expected to transform many of the products and services we use every day. Implementing the proposed remedies sooner rather than later would make it more likely that the remedies succeed in opening future competition, not just stopping illegal monopolistic conduct affecting the products we use today.

Authors