The Algorithmic Divide: The Disparate Impact of Social Media News Curation on Spanish Speakers

Diana Enriquez / Apr 15, 2024As you’ve probably noticed, this is an election year. A vast majority of registered voters in the United States will read at least some election news this year. 2016 and 2020 demonstrated how aggressive disinformation campaigns were for English speakers, but many still had trusted news channels where they could seek information. For Spanish speakers, the number of reliable news sites is declining, leaving 27 million Spanish-speaking voters with limited quality news coverage. This prompts a design challenge: how do we build reliable bilingual news channels, and distribute content successfully? But this challenge is met with clear obstacles: algorithms and content are not built to support bilingual users.

I am a bilingual internet user. I am also a voter, a UX researcher, and an interaction designer. Some of my favorite projects dig into the challenges of designing good automated systems. I started looking into the viral spread of misinformation around health and politics on social media channels in Spanish communities in 2020. What we see going into this election year is alarming. To address it, we need to scaffold existing translation efforts by community leaders on social media and improve automated recommendation systems for Spanish content.

Spanish news channels continue to lose funding, despite a growing population of Spanish and bilingual Spanish-English speakers in the US. When reliable news channels are shut down, informal actors step up to fill the void.

The New York Times ended its Spanish language coverage in 2019. The Union-Tribune in San Diego ended its Spanish coverage in 2024. Even Univision is losing some of its distribution contracts, which limits the distribution of its high-quality Spanish video content. Without these reliable sources, new actors emerge to provide news in Spanish with varying degrees of reliability. Emerging Spanish content includes individuals providing translation of English news stories on their own, citizen reporting, and, unfortunately, deliberate misinformation campaigns.

Social media design decisions impact what political news voters read.

Regardless of language background, many voters across the US turn to Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Youtube to see what their friends read or share as important news. This year Latino voters seem to be using social media channels more than other groups to find their news coverage. While news reviewed and shared by peers partially informs their news consumption, social media users also receive recommendations from the automated curation systems on these platforms. For example, YouTube is a particularly important channel for video-based news content; as younger voters turn away from TV news, YouTube is also an important place for targeted campaign ad placements. In fact, YouTube is the top source for political news for Latino voters. Spanish speakers in the US are 12% more likely to turn to YouTube for news than their peers in English-dominant households.

These websites replaced their human curation teams with algorithms.

We are at the mercy of past design decisions on content distribution that center high engagement. Views, likes, and shares dictate content visibility. As a result of these design decisions, content that prioritizes strong emotional responses receives more attention than more neutral, fact-driven content. When users turn to these channels as their main source of news, the burden is placed on the user to separate emotionally-optimized content from factual content. Unfortunately, rage on the internet spreads faster than positive news.

The default users these algorithms are designed for are English speakers, while other users must interpret and navigate content not designed for their comprehension on their own.

What is consistently visible in my own research: Spanish users are used to translating on their own, or relying on community translations for content from main website channels. A newsfeed for a bilingual speaker typically includes a mix of the viral content from the English channels and content in their native language. More specifically, the Spanish content is a mix of viral Spanish media, regardless of a user’s interests, and content they deliberately follow. With less infrastructure to build, curate, and promote reliable content in Spanish, these users are more likely to receive misinformation promoted by harmful actors who take advantage of the limited infrastructure to promote their own content.

When I compared the default newsfeeds of a new English user and a new Spanish speaker on Twitter in 2021, the information provided by reliable organizations was notably more diverse and in higher quantities for English speakers. Spanish speakers had some reliable content, but to increase their reliable news coverage they needed to take extra steps such as finding their own translation tools or interpretations of viral news stories to maintain the same level of coverage as their English-speaking peers. When I interviewed bilingual speakers and Spanish-preferred social media users, they reported nervousness about the limited Spanish news content available to them and the efforts they would have to go through to translate the English content. They often perceived English news as “more reliable” because the automated translation services on digital platforms are notably inconsistent in their quality of translation.

Disinformation campaigns have already targeted Spanish voters.

Representative Joaquin Castro (D-TX) described conspiracy campaigns through social media in Texas back in 2022. Campaigns targeting these voters ranged from disinformation about their voter registration status and right to vote to conspiracy theories about President Biden.

Examples of strong misinformation campaigns in Spanish included the efforts to spread conspiracies about Covid and the Covid vaccine in 2020.

Content produced by a handful of Spanish-speaking doctors spread like wildfire through the automated recommendation systems on Twitter and YouTube during 2020 and 2021. What started as advice to help navigate the uncertainty of COVID-19 quickly turned into unreliable information and conspiracies spread about treatments and vaccines. Even the automated monitoring systems for disinformation about COVID-19 were weaker for Spanish speakers on Facebook than they were for English speakers.

The user exposure to viral content I observed in 2021 showed very different pictures of news about covid and the vaccine – even with some conspiracy theories sprinkled in among the viral news about the vaccine for an English speaker, the Spanish channel was mostly conspiracy theories and debunked treatment theories for the virus promoted as “the best option available.” Spanish-speaking staff in hospitals and community centers noted how many of their patients came in very late for treatment, saying they waited because their news sources advised against medical treatment. By the time the state and public health system tried to address these viral disinformation campaigns, the conspiracy theories had taken deep roots into the narratives shared within local communities around me in New York, as well as those around my friends in Texas, California, and Arizona.

Tech platforms should prioritize three approaches to ensure Spanish speakers receive reliable news this election year.

They should:

- Fill the gap on reliable Spanish news stories that reach Spanish or Bilingual voters,

- Improve translation services to make necessary context accessible for Spanish-speaking voters, and

- Introduce a monitoring system for automated recommendation systems to stop disinformation campaigns before they embed themselves in community narratives.

Spanish news content and distribution requires focused investments, and these challenges require investments that consumers cannot make on their own. Funders can protect the Spanish news system by granting to existing Spanish news organizations and to journalists that can produce and distribute bilingual content.

Additionally, technology companies can improve their monitoring and automation tools to reduce the spread of viral misinformation. There are potential partners in the fact checking community: PolitiFact launched a Spanish fact checking program to address viral social media messages. These fact checks live in the PolitiFact social media channels and website, but they could be a valuable partner to social media companies. Editors curating Spanish messages acknowledge that the challenge is both at the platform-monitoring level and the individual level; stopping the spread of viral conspiracies also requires individuals to have gentle conversations with those who spread false stories. While automated monitoring is part of the solution, users mitigating false stories remain a crucial piece of combating disinformation. It is difficult to tell a family member or friend they are spreading false information - but it is an important piece of stopping fake news from spreading and causing harm. Conversations to address false information require a lot of patience, but they work.

Bilingual users on platforms like Twitter already do their best to provide side-by-side news translation services.

Some politicians tried to address it by mixing Spanish content in with their daily English content. Politicians like now Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Bercerra mostly tweets in English but posts some messages in Spanish on his private account to make accurate health information more accessible to Spanish speakers.

Sometimes mixed Spanish-English content in government feeds is met with resistance by English-speakers, but these feeds are generally more successful at reaching the broadest possible audience of bilingual speakers than the isolated Spanish channel vs. English channels are. (For example, the White House uses both an English channel and a Spanish channel. Spanish speakers often mentioned following both, if they followed the White House, because they wanted to check both feeds for accuracy.)

Many Spanish speakers go to English sources first on social media because they believe these are less likely to be “corrupted” by poor translation, then they go look for translated materials. When the topic is important, they mention they will review the sources side-by-side to make sure they understand the story and information they are reading. For instance, in my research on translated content on Twitter users: nurses on ‘Spanish Twitter’ used their channels to present health-related tweets in English next to a Spanish translation. They knew their audiences wanted to see both, so they gave them both. For important issues like health and politics, having the option to make an article bilingual in this staggered format may be reassuring to other readers who are learning to trust translated materials and want to verify them for themselves. These community members provide an important, and uncompensated, service for their communities. This higher touch, human-design process makes a big difference in making content accessible and building trust. Their work could also be promoted through the recommendation services built into these platforms as a useful translation tool.

What we learn from community efforts like these individual translators is producing high-quality bilingual content that juxtaposes English and Spanish is a step towards rebuilding trust.

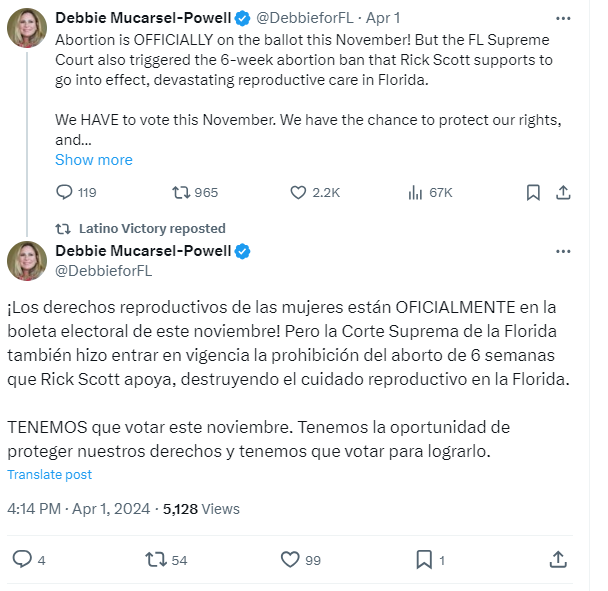

Some campaigns use a full English Tweet and then present it with the full translated tweet beneath it:

Another design option that is especially popular in public health circles is to make the thread longer and include a sentence in English followed by the mirrored sentence in Spanish. This lets Spanish speakers see the thread is bilingual throughout the thread.

Longer term, tech companies need to improve the language capacities on the teams handling the design, research, and development of core product features like content recommendation if they aim to continue expanding internationally without promoting disinformation.

In many of the tech teams where I conducted my research, I was the only native Spanish speaker or there were a handful of individuals scattered between research, design, development, and product management with varying degrees of Spanish proficiency. Automated disinformation monitoring and tagging systems rely on creating good training data. Producing this training data requires context-knowledgeable researchers and product managers who can interpret the data and make good choices about the algorithms they design and implement. Spanish versions of apps sometimes exist but usually receive limited funding and support compared to the default English version. Even surveys and user research translated for Spanish users was left in a secondary pile of data and sometimes never addressed.

Meanwhile, these companies expect to serve diverse populations or expand internationally. Some of the design challenges for bilingual content include handling monitoring for content quality and reputability. Other issues include improving the overall recommendation algorithm, which requires better technical and contextual translation within the team. Poor translation handles literal word translations and sometimes chooses the incorrect word due to its multiple meanings in different contexts. Good translation happens through reliable word associations and a grasp of contextual meaning. Contextual translation requires a clearer investment in the culture of language and a working knowledge of living language as it evolves (i.e. new slang emerges every day, and words fall out of favor or mean different things in different Spanish speaking countries). Automation is full of design choices. It is worth investing in the tools needed to make good design choices.

Authors