Tech Companies Sit on Sidelines While Korean Children Are Drawn Into Digital Sex Trafficking

Heesoo Jang / Sep 13, 2022Heesoo Jang is a PhD student and a Royster Fellow at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a graduate affiliate with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life (CITAP).

A mass sex trafficking crime that happened in South Korea was only possible with the use of the combined affordances of several Internet platforms and cloud storage providers, the majority of which are headquartered in the West. These platforms are less rigorous when it comes to monitoring material that is written in non-Western languages (i.e., Korean) and less beholden to local law enforcement, factors that combine to make it easier for the criminals to obscure their activities. Reforms are necessary to prevent future crimes, and to hold highly profitable, often publicly traded tech firms to account for their roles.

Background on the Nth Room Crimes

Between late 2018 and 2020, a network of chat rooms with sexually violent content appeared on Telegram—a messaging platform launched back in 2013 by two Russian-born brothers, Nikolai and Pavel Durov, that is now headquartered in Dubai. The “Nth Room case” collectively refers to the series of online ‘sextortions’ that happened in South Korea that was revealed to the public amid the COVID-19 pandemic back in 2020. The crime involved blackmail, sex trafficking, and online distribution and selling of sexually exploitative videos of children.

The extent of the sexually abusive content was staggering. At least 103 known victims, of which 26 were minors, were forced to upload sexually explicit videos to Telegram chatrooms. Oftentimes these videos were violent, with the victims engaging in self-degrading and self-harming activities. One victim was only in middle school when she was extorted for over 40 sexual abuse videos in 2018. At least 260,000 users accessed these chatrooms and used cryptocurrency to pay for these child sex abuse videos. Sometimes, the perpetrators allowed participants access to these rooms if they sent self-produced videos of themselves participating in a rape, either alone or in groups. Also, the sexual abuse did not stay online. The perpetrators often opened events in these group chatrooms, where they would invite participants to pay money to participate in the group-rape of underage girls. These rapes were recorded and sold online as “premium” content.

Moon Hyung-Wook, who used the nickname “God God,” created eight group chats on Telegram after their ordinal numbers (1st room, 2nd room, etc.), which led to the name of the case: “Nth room.” He messaged potential victims on Twitter, claiming that their private photos had been leaked. When the victims visited the link, their personal information was collected, which was used to coerce the victims to send Moon sexually explicit photos and videos on a daily basis. Cho Joo-bin, who used the nickname “Baksa,” a term that refers to someone with a doctorate, imitated Moon’s crime and approached potential victims on Twitter with fake job offers. Cho also collected personal information and photos during the fake interview process, which were later used as a blackmailing tool.

Both Moon and Cho had their own cartel that helped them identify and lure victims, threaten them, and manage the chatrooms and their money flow. In November 2021,the South Korean Supreme Court finalized prison sentences of 34 years and 42 years for Moon and Cho respectively, for coercing minors, sexually harassing them both online and in person, threatening them to distribute the sexually explicit videos to friends and families, and forcing them some of the victims to write sexually explicit phrases on their bodies through self-harm.

Multiple Western Tech Firms Exploited by the Traffickers

Telegram was used as the main venue for these crimes. One distinguishing characteristic of this platform is its encryption function. Telegram offers server-side encryption by default, which means that user data is hidden from internet service providers, Wi-Fi router interceptions, and other third parties. For one-on-one conversations, Telegram allows end-to-end encryption as well. Telegram has been building its reputation for security by claiming that its services are “more secure than mass market messengers like WhatsApp and Line.”

News coverage and public discussion around the Nth Room case largely focused on Telegram. However, the mass digital sexual trafficking happening in Korea is not only about Telegram. These crimes have been only possible because of the co-existence of a variety of social media platforms that served different purposes in these series of crimes, including but not limited to Twitter, Telegram, Facebook, Discord, and even file-sharing services such as Google Drive and Mega Drive. Each platform is used for different purposes.

Twitter was used to find victims. Traffickers reportedly used hashtags and keywords to spot female users who had uploaded sexually explicit content. By impersonating members of the South Korean Cyber Terror Response Center, the traffickers approached the victims via Twitter direct messages. They accused their targets of distributing obscene material, then demanded personal identification and critical information, including identity numbers, occupation, home address, the names of their school or company, which was then used for blackmail.

After obtaining these pieces of information, the traffickers herded the victims to Telegram, where purchasers were waiting. There were hundreds, and even thousands, of purchasers in each Telegram room. These telegram group chatrooms were not public and participants needed invitation links to enter these chatrooms. Some chatrooms required participants to pay “entrance fees” to receive invitation links. Cho even required photo IDs from purchasers to ensure limited access to these chatrooms. There were hundreds, and even thousands, of purchasers in each Telegram room.

In these chatrooms, the victims were forced to upload images and videos of sexual abuse and self-harm. As mentioned, several victims were also raped by users who paid money to encounter the women in person, sometimes in the context of group rape. The traffickers used the personal information they collected to threaten the victims, claiming that they would send the images and videos to the victims’ family, friends, and colleagues using the addresses they had acquired. Telegram stickers exacerbated the harm occurring in these chatrooms, as chatroom participants made DIY animated stickers and emojis with the victims’ faces and bodies and shared them for fun.

The cryptocurrency used in Cho’s sexual abuse cartel was Monero. There were different types of chatrooms that purchasers could access depending on the amount of money they paid. The higher the number of the room, the more severe the sexual abuse was. To get access to the lowest level room, participants paid approximately $200. Access to the second room, which included underage victims, started from approximately $700, and access to the third room, which showed personal information of the victims, started from approximately $1,500. These rooms were regularly removed and recreated, which made them difficult to find without invitation links. The criminals then used Facebook’s closed group pages and Facebook Messenger’s group chatrooms to advertise invitation links to these Telegram rooms. These same features were used to distribute sexually explicit content.

Lastly, cloud services, such as Google Drive, Mega (previously Mega Upload), and Dropbox were used to distribute these videos in chunks. Team Flame, the investigative journalism team that first investigated and reported the Nth Room case, noted that it is unfortunate these cloud services are brought up less when talking about digital sex trafficking in South Korea, when in fact the majority of illegal sexual abuse content (including those of minors) are distributed through cloud services. The convenience of saving, downloading, and sharing large amount of videos makes cloud services attractive to criminals. According to Team Flame, perpetrators casually warned each other to not use domestic Korean cloud services, meaning these Western-based cloud services were intentionally chosen. The uploading, managing, selling, and distributing of the sexual abuse contents were all managed through the URL links provided by these cloud services.

In summary, this mass sex trafficking crime abused the affordances of multiple tech firms. That these firms are headquartered in the West is not incidental, as their moderation and safety practices are less rigorous for material primarily in non-Western languages, such as Korean. The same platforms are less liable to Korean law enforcement, which makes it easier for criminals to operate and obscure their activities. The choice to use Telegram, Facebook and Google Drive was strategic.

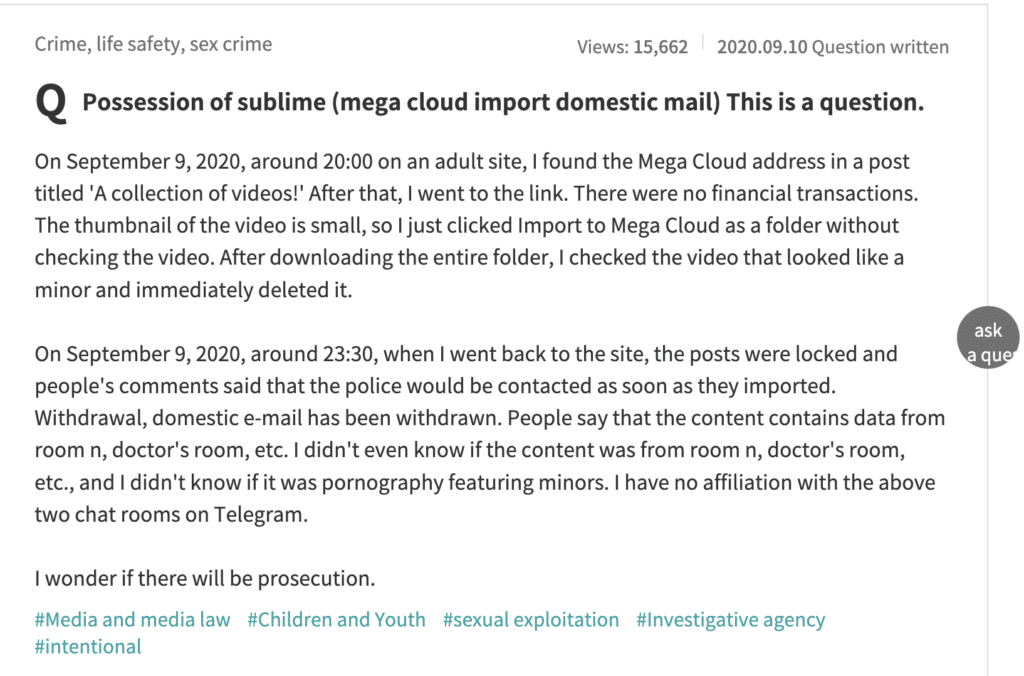

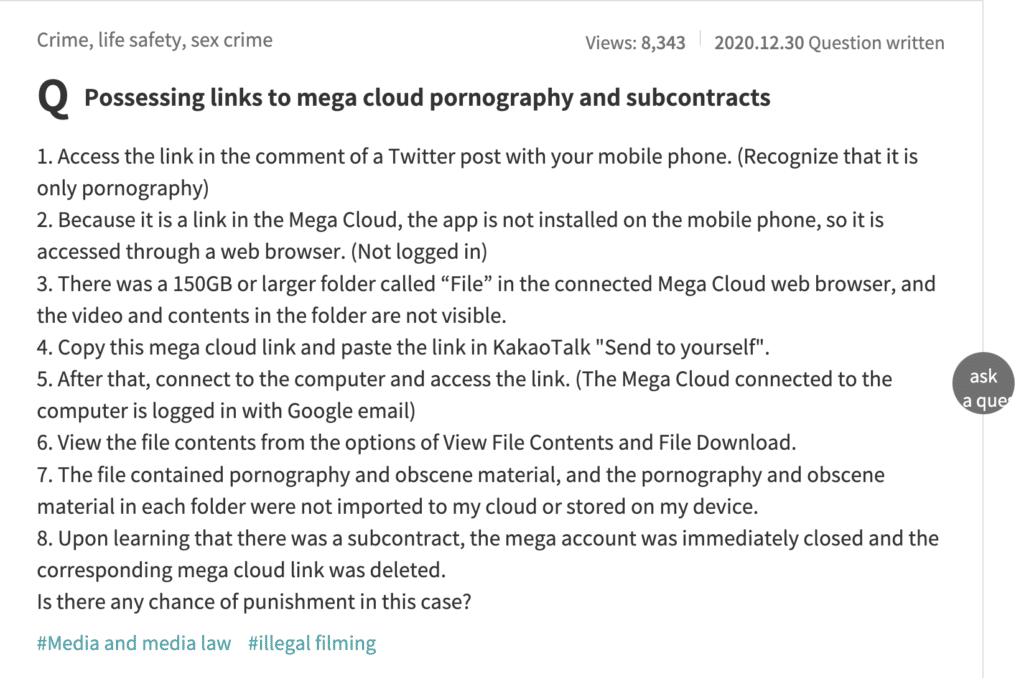

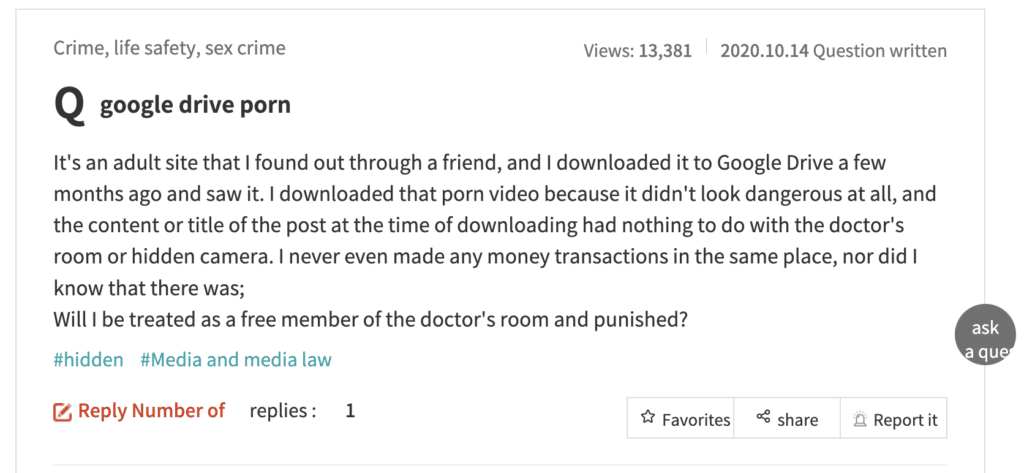

Above are three screenshots of questions that came up on a law consulting online platform (https://www.lawmeca.com/) after Korean law was revised to punish those who possessed or watched illegal sexual videos of minors linked to the Nth Room case (translated via Google Translate). Many questions asked if watching sexual exploitation videos via cloud services are subject to legal punishment, which shows that many of the sexual abuse content artifacts were distributed through cloud services.

What Are the Tech Firms Doing to Mitigate Harm? Not Much.

What have transnational tech companies that were involved in the “Nth room” digital sex trafficking scandal done since the network was revealed? Not much. As of September 2022, local media have reported similar crimes to “the Nth room case” still ongoing in South Korea on platforms including Telegram and Discord.

ReSET, a Korean non-profit organization that fights against digital sex trafficking, has reported new networks of Telegram chatrooms that model the “Nth room” case. In these chatrooms, perpetrators receive “missions” for “slaves” from participants and upload sexually exploitative content. Sometimes they sell “admission tickets” to participate in the sexual abuse in person as “invited men.” Other forms of prevalent sexual abuse include what is referred to as “acquaintance humiliation (지인능욕)” in Korean, which refers to photoshopping a person’s face to a naked body with sexual connotations to publicly harass the victim. Advanced deepfake technologies have exacerbated the harms caused by these crimes.

After Cho and Moon were arrested for sextortion on Telegram, the main venue of these sex crimes moved to Discord. The sex abuse videos that were created and distributed on Telegram were migrated to Discord and the selling of these content has been ongoing ever since. Neither of these platforms have officially acknowledged these crimes happening on their platforms and have not done any change to mitigate the harms.

Google has been accused of exacerbating secondary abuse of the victims for its lack of mitigation strategies towards digital sex trafficking in South Korea. Team Flame, which first reported on the Nth Rooms, has stated that Google has the most severe secondary abuse problem. When the Nth room crimes were revealed, Google was found responsible for exposing the victims’ names when people searched for keywords related to the Nth room case. Google responded to this accusation stating that Google’s content moderation heavily relies on AI and that it is hard for the AI to know that the “Nth room” case is a socially-controversial issue.

The time it takes for tech companies to respond to requests of removing sexual abuse content has been too slow, which only exacerbates the spread of these content. According to the Korean digital sexual trafficking citizen auditing group – a voluntary group of 801 citizens recruited and trained by the Seoul Metropolitan government to audit platforms for sexual abuse content – only 20% of their requests were handled within a day. 80% of the requests took more than 24 hours, with 42.5% taking more than a week. In an interview with the JoonAng Daily, Lee Dukyoung, a South Korean digital undertaker, stated that domestic platforms such as Naver and Daum Kakao handle requests within 30 minutes, while transnational platforms mainly from the West are often unresponsive even after 60-70 requests for a post.

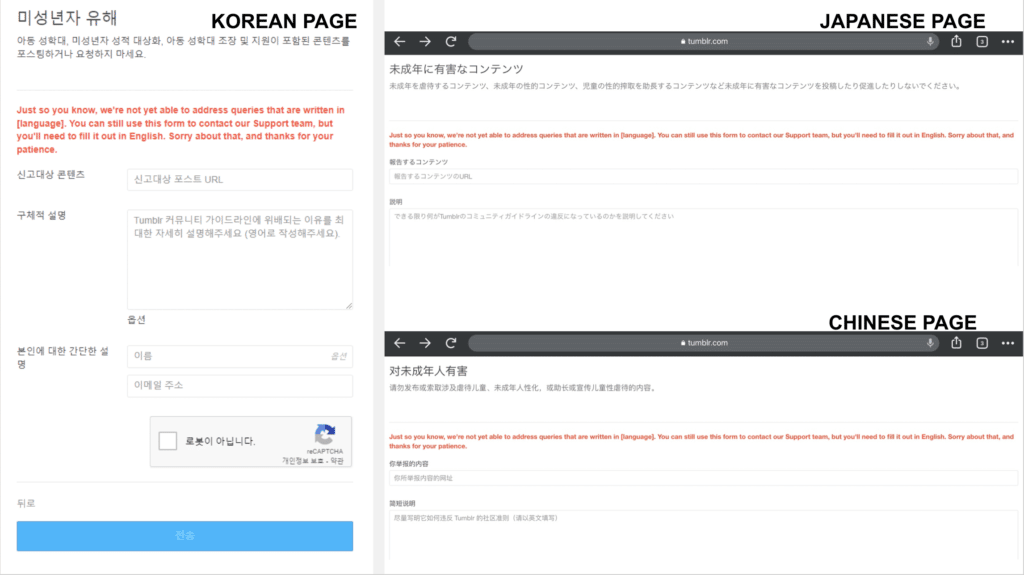

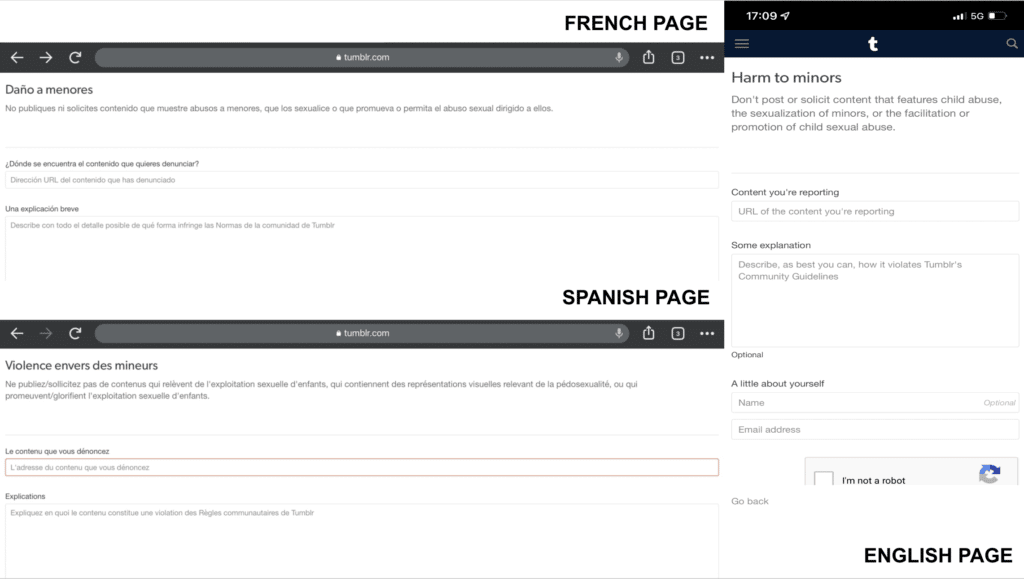

Language barriers are also a major issue, particularly when platforms do not provide users with ways to reach out in their native language. Tumblr, another popular social media platform headquartered in New York City, requires its users outside of the West to use English for reporting posts that violate community guidelines (even until today, when last accessed on September 13, 2022). To contact support and get help, you must have a command of English. This is a problem given that Tumblr has been accused of a key node in digital trafficking and sexual abuse. Back in 2017, Tumblr was responsible for over two-thirds of South Korean government’s removal requests of sexual content to internet service providers.

Tumblr’s “report violation” page in different languages. Tumblr users are required to report content in English in non-Western language-speaking countries, including regions that use Korean, Chinese, and Japanese. The pages in these languages all show the same English statement in red: “Just so you know, we're not yet able to address queries that are written in [language]. You can still use this form to contact our Support team, but you'll need to fill it out in English. Sorry about that, and thanks for your patience.” On the other hand, Tumblr accepts content violation reports made in English, Spanish, and French.

Tech Firms Must Do More

The main crime venue of these online child sexual exploitation has apparently moved to Discord since 2020, but Discord has remained silent about the abuses and harms happening on its platform only to become “a haven for sexual exploiters.” South Korea is, sadly, used to this silence of transnational tech platforms by now. Before Discord, Telegram has ignored South Korean governments’ data requests regarding the nth room case a total of seven times since October 2020. In June 2022, however, Telegram reportedly submitted to several data requests from Germany, including information on users suspected of child abuse, for the first time since it started service.

Furthermore, online child sexual exploitation through these transnational social media platforms is not solely limited to South Korea. ECPAT, a global network of anti-child trafficking organizations, has already confirmed similar cases of online child sexual abuse in Taiwan. Another report from ECPAT also underlines the increasing use of social media platforms (such as Facebook) in child sexual exploitation in South Asian countries.

Transnational tech firms must do more to address digital sex trafficking. They should:

(1) Officially acknowledge and address the harms they are part of;

(2) Investigate the unexpected ways their affordances can be abused to perpetuate harm;

(3) Research both short-term (e.g., reducing response time to requests) and long-term solutions (e.g., changing platform designs to prevent abusive use) to mitigate these harms;

(4) Work with researchers and experts to design community guidelines and what it means to violate them in a way that is sensitive to the local context instead of blindly accepting Western-centric definitions of these harms; and

(5) Provide more efficient ways to request the removal of abusive content and get the support they need from the platforms.

Transnational tech companies—largely Western-headquartered—enjoy popularity among a global range of users and make large profits in these markets. Yet, these tech companies are not responsive to the harms taking place on their platforms. The Nth Room case exposed the apparent lack of concern that transnational tech firms have for victims of these crimes perpetrated on their platforms and with their tools. It is time for these tech firms to make the necessary commitments and investments required to secure their services in every market and language in which they operate.

Authors