"Suspension Warnings" Can Reduce Hate Speech on Twitter

Justin Hendrix / Nov 22, 2021An account ban is perhaps the most definitive action a social media company can take against an individual found to be propagating hate speech that violates the platform's terms of service. But while individual account bans and suspensions may be necessary to address some bad actors, what if over time these tactics do not ultimately reduce the overall prevalence of hate speech on a platform? What if other, less severe tactics might produce a better result across the whole of the network, creating a more healthy information environment?

Twitter has long had a problem of racist abuse, which came to the fore again this summer when users spread hate targeting the England football team following the Euro 2020 Final. The incident forced the company to look more closely at the problem of racism and hate on its platform in order to address public concerns.

In this context, a group of researchers at NYU's Center for Social Media and Politics designed a novel experiment on Twitter to get at "whether warning users of their potential suspension if they continue using hateful language might be able to reduce online hate speech." Their findings are published in a paper titled "Short of Suspension: How Suspension Warnings Can Reduce Hate Speech on Twitter" in the journal Perspectives on Politics.

Referring to "a large and still growing body of work from the literature on deterrence that provides evidence that sending warning messages in cyberspace represents an important avenue for deterring individuals from malevolent behavior," the researchers used a hate language dictionary developed by Penn State professor and former NYU student Kevin Munger-- who himself has experimented with using bots to combat racism on Twitter-- to parse 600,000 tweets downloaded on July 21, 2020. The researchers note this date fell within a period when "Twitter was flooded by hateful tweets against the Asian and Black communities due to Covid and BLM protests, respectively."

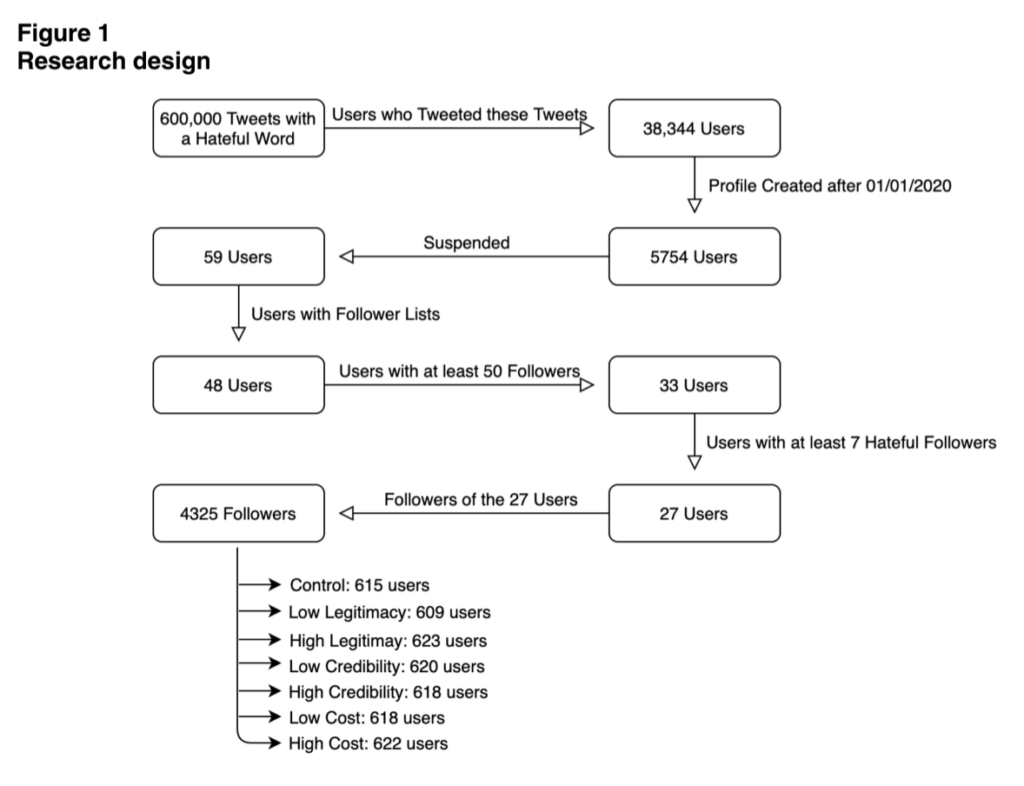

The researchers then went through a process to identify a subset of users suspended for their hateful tweets that yielded a corpus of 4,325 followers of selected suspended accounts who had demonstrated they were also at risk of suspension.

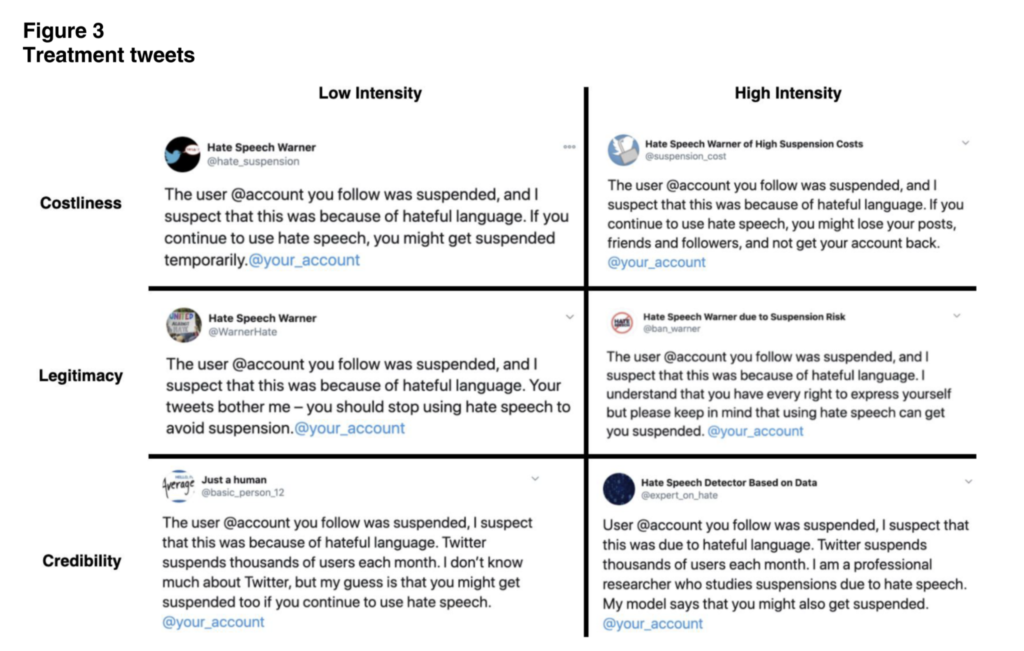

Next, the researches split this subset of 'at risk' accounts into six treatment groups and a control group, in order to test the effectiveness of a set of warning tweets sent by accounts operated by the researchers. The warning tweets differed in their tactic across three dimensions- "the costliness of the suspension in the eyes of the treated, the extent to which they perceive our warning as legitimate, and the degree to which they perceive [the researchers'] warning as credible." The warning tweets included the following language:

The results were positive- "only one warning tweet sent by an account with no more than 100 followers can decrease the ratio of tweets with hateful language by up to 10%, with some types of tweets (high legitimacy, emphasizing the legitimacy of the account sending the tweet) suggesting decreases of perhaps as high as 15%–20% in the week following treatment."

A keen reader might wonder why Twitter might not issue such warnings itself. An even more keen reader might recall that Twitter has in fact been testing warning prompts on potentially offensive tweets for some time, and has also reported positive results. So, what's different here?

The researchers say their method warns users who have already demonstrated the use of hateful language, and that they combine warning tweets with notice of the recent suspension of a specific account that the user followed. They note this is a methodology Twitter could adopt, perhaps after exploring various considerations at platform scale-- such as whether the intervention prompts backlash that makes the problem worse. Or, it could be implemented by civil society groups working to protect the interests of particular targeted communities.

There are, according to the paper, particular design features of Twitter that make this type of intervention possible. Indeed, a similar methodology may work elsewhere, but social media firms will have to be willing to take decisions that may negatively impact their short term profits or growth to address the problem.

For instance, the day before the NYU paper was published, the Washington Post reported that Facebook has ignored solutions its own researchers put forward to address racism and hate speech. "Far from protecting Black and other minority users, Facebook executives wound up instituting half-measures after the “worst of the worst” project that left minorities more likely to encounter derogatory and racist language on the site," the newspaper reported. Certainly, no intervention at the user level will address the problem of racism or hate speech if social media firms refuse to adequately address it at the platform level.

Authors