Survey: U.S. Attitudes Toward Tech Regulation Don't Always Fit Partisan Boxes

Justin Hendrix / Mar 9, 2022In September 2021, the Wall Street Journal published the first of a series of reports based on leaked documents from Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen. As more journalists got access to the internal communications and research documents, a torrent of headlines on the externalities and harms to society produced by Facebook and Instagram seemed to produce a new urgency on Capitol Hill to pursue new regulation of the tech industry. A flurry of new hearings were called in the House and the Senate to consider what can be done to make social media safer and more complementary to democratic values.

It turns out that adults in the United States did not need to see such evidence to know something is wrong on the internet, and to broadly agree that something should be done about it.

A substantial survey of 10,226 American adults conducted between July 30 and August 26, 2021 by Gallup and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation– released today– seeks to add “nuance and texture to the ongoing public conversation about the regulation of online content and responsibility for the internet’s governance,” even as some of its topline findings are rather blunt:

- 77% of Americans distrust information they see on social media

- 92% are concerned about how technology companies use personal data

- 90% agree that social media makes the spread of misinformation, extreme points of view and harassment or threats easier

- 71% believe the internet does more to divide us than bring us together

- 76% say social media makes it easier to interfere with elections

- 57% somewhat or strongly believe that expressing political views has a significant impact on politics

- 53% say social media has a negative impact on them

While such figures may not be surprising to readers of Tech Policy Press, there is more to this survey– which was complemented by focus groups– than similar assessments in the past. This study sought to look more deeply at views on questions related to free expression, privacy rights, content moderation, and what types of solutions people expect from policymakers. And, it produced some results that may force those policymakers to consider a public not so neatly divided on these issues along party lines.

“Most research has looked at how people use social media, and some research has asked how they feel about it. Less has considered how they feel about it in relation to politics and in relation to society,” an advisor to the report, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill journalism and media professor and Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life researcher Dr. Shannon McGregor told Tech Policy Press. “And I think most importantly, what do Americans want to be done about it?”

Views on Social Media and Political Participation

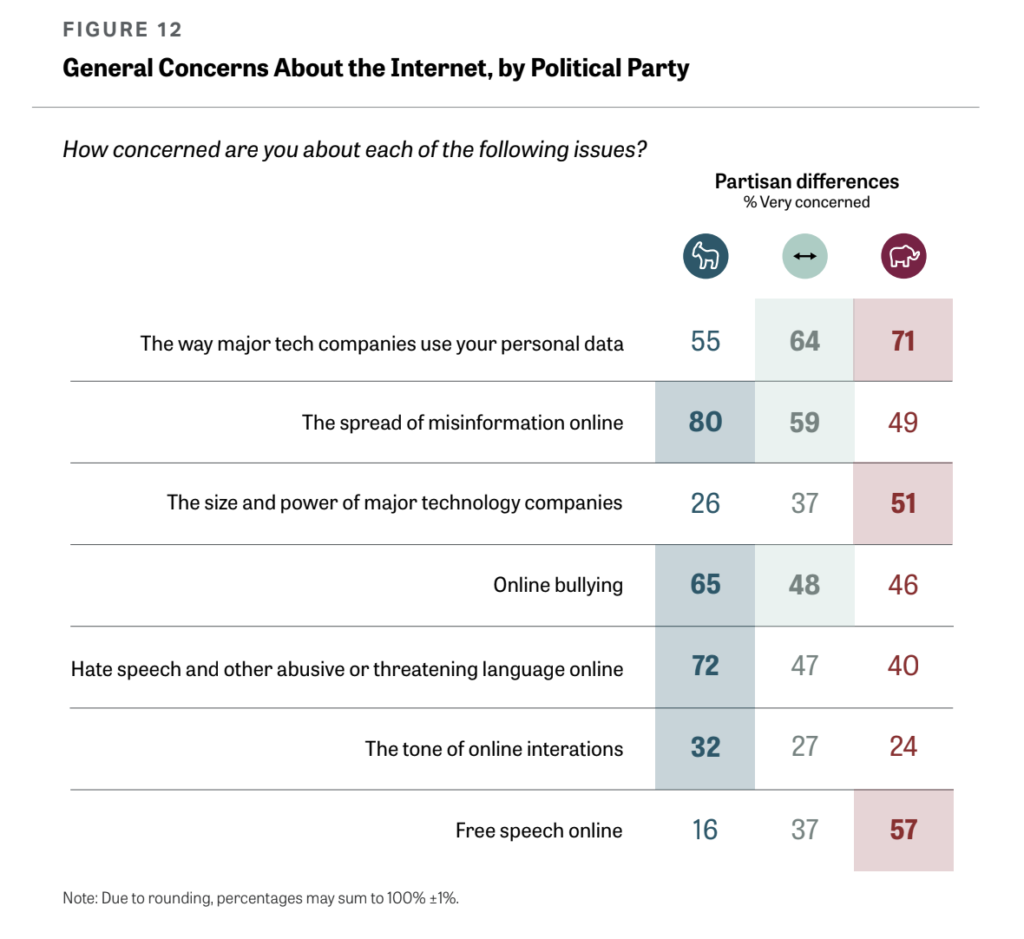

While the survey turned up a set of relationships between views on democracy, civic and political participation, the consumption of information and the use of social media that get beyond typical red versus blue dynamics, there are some notable results that point to partisans differences. For instance, Republicans are more concerned about privacy, the size and power of technology firms and free expression than Democrats, while Democrats are more concerned about the spread of misinformation, online bullying, hate speech and other forms of abuse.

But there are also key demographic differences in perspective, which hold beyond political affiliation. Gender is a driving factor: women, and most notably Black women, are most concerned with harmful speech. In contrast, the survey says “White men report the lowest levels of being very concerned about these issues.” Age also plays a role, as older people are more concerned than younger people about online abuse.

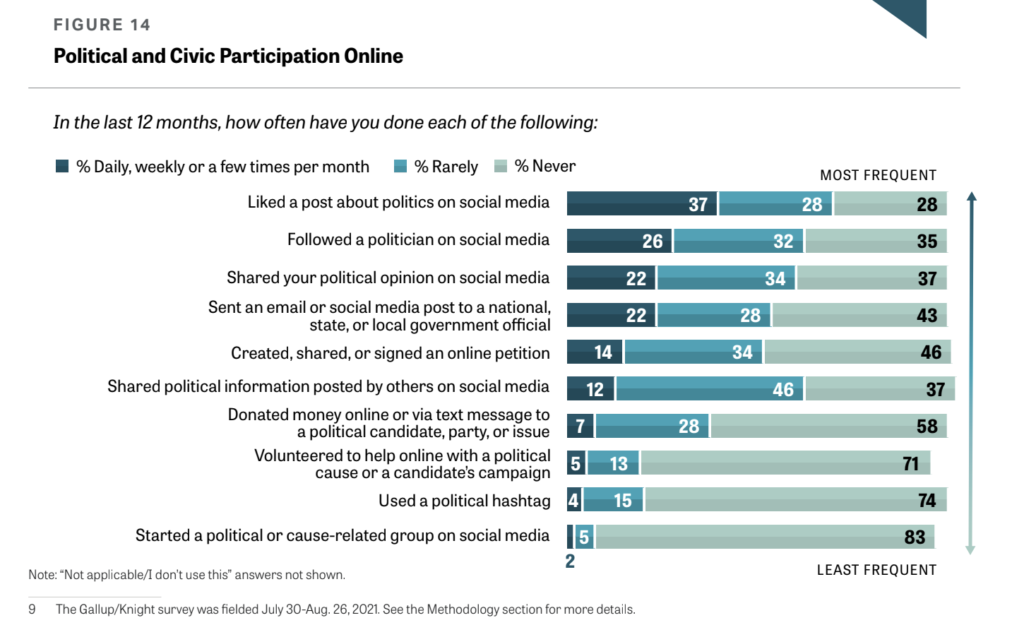

The survey also reinforces the view that most people are simply not using social media to engage heavily in politics. While a subset of adults regularly like posts about politics (37%), follow a politician (26%), share their own opinions (22%) or information on politics from others (22%), the great majority across the ideological spectrum rarely or never engage in these or other political activities such as engaging with government officials, participating in petitions, donating to causes or candidates, using political hashtags, volunteering on a cause or campaign, or starting political or cause-related groups.

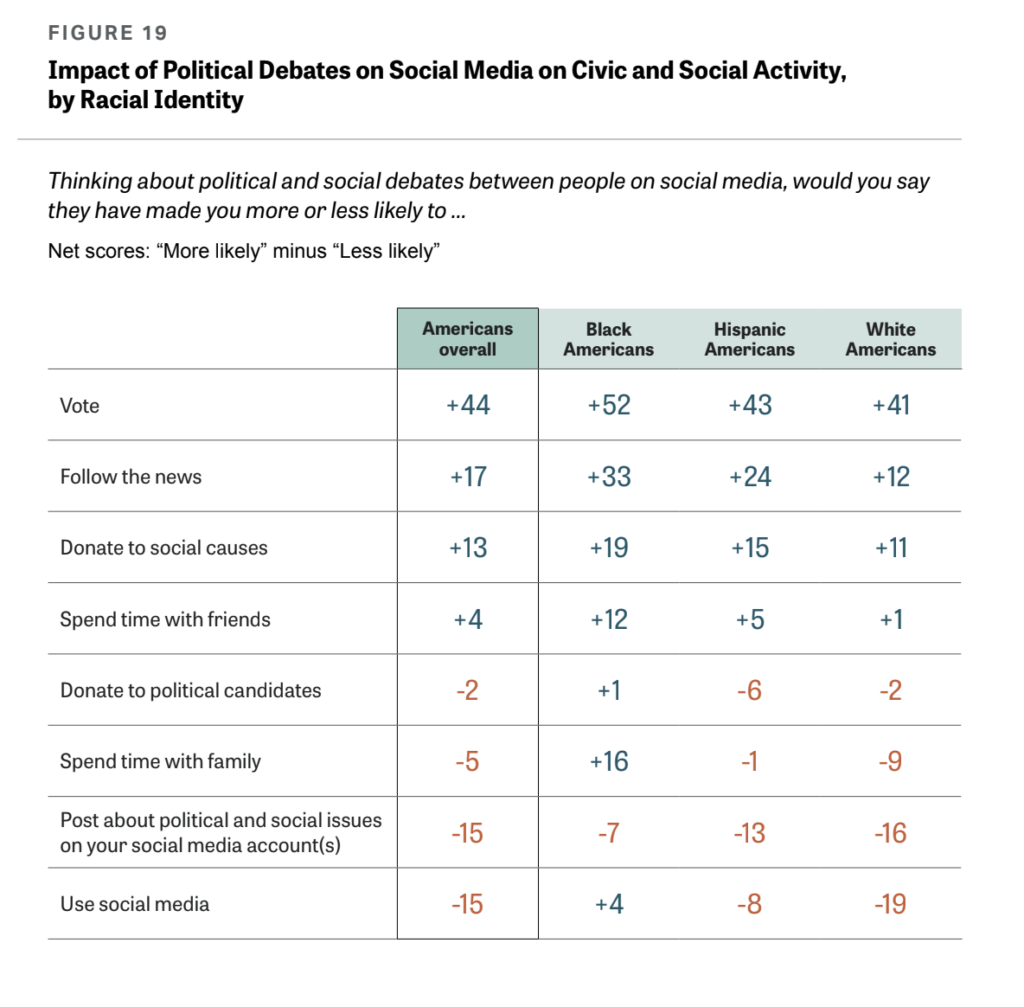

These findings alone, however, aren’t the whole story about social media’s impact on political engagement. The results also suggest that social media across the board has a net positive effect on offline political behaviors such as voting, news consumption, and political engagement with government officials and social causes. For instance, Americans overall say debates on social media make them significantly more likely to vote. Some groups see more of a positive effect than others: Black Americans are the most significantly more likely to vote, to follow the news and to donate to social causes due to their exposure to online debate.

Attitudes Toward Tech Reform

When it comes to questions on tech reform, there are some confounding questions as well as some that produce something approaching consensus. For instance, when asked generally about who should be responsible for content posted on social media and whether it should be removed or not, no single solution attracts majority support. But a majority (57%) does agree that the onus should be on social media firms to identify false or misleading content, while a smaller minority (32%) believe that responsibility should fall to the user. Majorities are more concerned about false information than about censorship, and there are concerns in the majority about anonymity on social media platforms and the role it plays in harmful and abusive content and misinformation.

Majorities also appear to agree on the essential characteristics of good democracy in the United States, from the idea that people should choose their leaders in free elections to the idea that people should have the right to peaceful protest and to a free press.

But when it comes to the current state of the country’s democracy, majorities also believe we are far from achieving those ideals. 65% believe that “even though we elect our leaders, a few people will always run things,” while less than half believe that “all adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote,” or that “elections are free and fair,” for instance. And, the respondents have internalized the idea that leaders are operating not just from competing positions but from a different base of facts: 69% disagree that “political leaders generally share a common understanding of what is true, even when they disagree on policy.”

“There are things that we have a shared understanding in around democracy. We also have shared concerns about social media as it relates to our democracy, and we see shared benefits as it relates to our democracy,” said McGregor. It is important, she says, for policymakers to consider not only the unintended harms of social media, but also to look at what their constituents regard as its benefits, and what aspects of social media drive positive political participation.

To peel the onion on perspectives on potential reform, the designers of the survey used forced-choice questions and a cluster analysis to combine segments based on attitudes such as how social media companies should be held responsible or liable for harmful content online with views on key democratic principles, such as free expression, and measures of other concerns, including privacy. This methodology led to six unique segments identified more by their views on these dimensions than by their position on the political spectrum. The traits of each of the segments lead to different views on how content should be moderated, for instance, and on questions related to privacy. The segments, in brief, include:

The Reformers (30%)

Highly engaged internet users and active consumers of news, The Reformers are politically active and tilt heavily toward the Democratic Party. They tend to favor more intervention by the government and social media companies to address social harms online.

The Concerned Spectators (19%)

While it also leans slightly Democratic, this segment is less politically active online. They are worried about the spread of misinformation and other hurtful content online and how social media companies use their personal data, but they are split on whether government or social media companies should be responsible for moderating content online. This group skews older and tends to consume more traditional network news.

The Traditionalists (9%)

While The Traditionalists recognize the potential for harm online, they are also wary of government being the arbiter of free expression. This segment tends to take a laissez-faire approach and assign responsibility to individuals and social media companies. They have mostly mixed political affiliations and engage less frequently online.

The Unplugged and Ambivalent (4%)

The smallest among the segments, this group tends to be offline, disconnected from news and mixed in terms of partisan attachments. They hold conflicted and contradictory views on who should be responsible for harmful content online.

The Unfazed Digital Natives (19%)

The youngest of the segments, these digital natives tend to use the internet for entertainment more than for news or politics. They are less concerned about the potential harms of content online than most others and favor individual responsibility and a hands-off approach by the government. Nevertheless, they support some degree of content moderation by social media companies.

The Individualists (19%)

Avid consumers of right-leaning news, this politically engaged group is also the most homogenous. They show a strong affinity for the Republican Party, and concerns about free expression and censorship online outweigh any apprehension about hurtful content. They favor individual responsibility and as little intervention by the government or social media companies as possible.

Something Needs to Happen– But What?

No matter the differences among these segments, a majority of the respondents (62%) agree that elected officials pay “too little” attention to tech issues and technology companies.

I asked McGregor what message she would want to leave with policymakers eager to do something if she were to invited to testify on the results of this survey. She said the results may seem slightly confounding, since they force us to think beyond partisan binaries, but that lawmakers should put the focus on “protecting those most vulnerable to harms” while balancing efforts to do so with an understanding of the benefits people see from social media. Coming to conclusions on some of these questions will be hard, though, given they are driven by deeper cleavages.

“Who are we protecting and what do we want to protect? And what do we think is not worthy of protection? These are questions we're having in our country that don't have anything to do with social media and that are about democracy," said McGregor. Either way, when it comes to tech policy, one thing Americans seem to agree on is that “something needs to happen,” she said.

Whether Congress will do something, rather than nothing, remains to be seen. But perhaps a more complex understanding of their constituents' views will inspire more nuanced legislative solutions that can overcome the divisions voters believe social media makes worse. Only time will tell.

Authors