Supreme Court Justices Question Standing, Evidence in Murthy v. Missouri

Gabby Miller, Ben Lennett / Mar 21, 2024

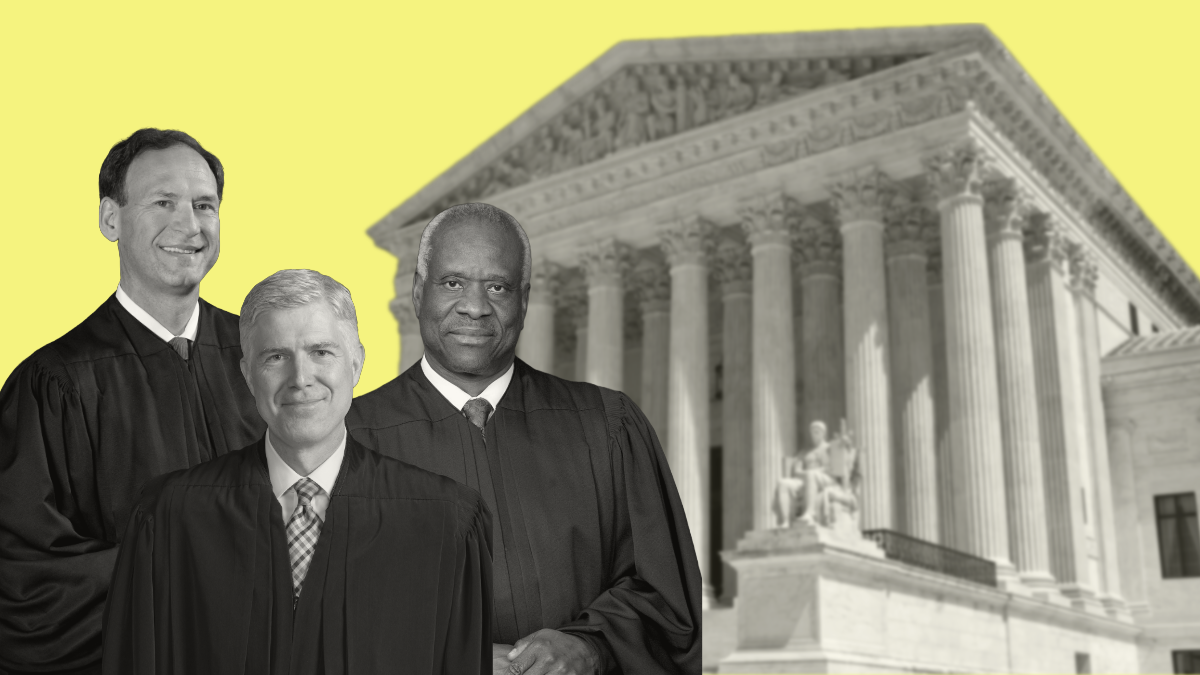

Justices Alito, Gorsuch, and Thomas wrote in dissent of the stay of the modified injunction in Murthy v. Missouri.

On Monday, March 18, during the oral argument for Murthy v. Missouri, US Supreme Court justices were tasked with examining whether the government coerced social media platforms to “censor and suppress” disfavored speakers and viewpoints by threatening retaliatory action.

The three questions before the Court included whether respondents in the suit – the states of Missouri and Louisiana and five individual plaintiffs – have standing to bring the case, if the government’s conduct transformed private social media companies’ content moderation decisions into state action, and whether the terms and breadth of the lower court’s injunction were appropriate. Much of the argument, however, revolved around the quality of the evidence before the Court. The government argued the lower courts cherry-picked certain communications and presented some out-of-context. (Tech Policy Press' review of the record found substantial reasons to question it.)

The plaintiffs’ litigation strategy mirrored its approach to the initial suit. Solicitor General of Louisiana and Counsel for the plaintiffs, Benjamin Aguiñaga, kicked off his remarks by zeroing in on the volume of evidence presented to the Court. “Government censorship has no place in our democracy. That is why this 20,000-page record is stunning,” he told the bench. “The district court, which analyzed this record for a year, described it as arguably the most massive attack against free speech in American history, including the censorship of renowned scientists opining in their areas of expertise.”

But despite the voluminous record, many of the justices struggled to find the evidence sufficient for plaintiffs to bring about the suit in the first place. In one of the most telling exchanges, Justice Elena Kagan asked Solicitor General Aguiñaga to point to “the single piece of evidence that most clearly shows that the government was responsible for one of your clients having material taken down.”

In response, Aguiñaga pointed to “censorship” claims made by plaintiff Jill Hines, a Louisiana resident and anti-vaccine activist. Hines, who runs the Facebook pages of both Health Freedom Louisiana and Reopen Louisiana, alleges that after the White House embarked on a July 2021 “pressure campaign” to suppress certain health information online, both her Facebook groups were deplatformed. She also claims that she was censored for re-posting content from Robert F. Kennedy Jr., one of twelve people referred to as the ‘disinformation dozen.’

Hines alleges the action against her account is supposedly traceable to the government via a May 2021 email from the White House to Facebook saying its ‘dedicated vaccine hesitancy policy’ didn’t seem to be stopping the disinformation dozen. (Facebook refused to remove the twelve individuals outright, despite prior urging from the government.)

Yet, Justice Kagan questioned the idea that an email from the government, sent two months prior to the actions Facebook took against Hines, should be the deciding factor in the Court’s determination over whether content moderation was the result of government action, as opposed to the platform’s decisions. “A lot of things can happen in two months,” Justice Kagan said to the plaintiff’s counsel. “So that decision could have been caused by the government's email, or that government email might have been long since forgotten. Because there are a thousand other communications that platform employees have had with each other, a thousand other things that platform employees have read in the newspaper,” said Justice Kagan.

Solicitor General Aguiñaga argued that the traceability link is a “temporal one,” and that the “thousand other emails between the White House and Facebook in those two months” speaks to the volume of the interactions between the platform and the government. But Justice Kagan didn’t buy this standard for traceability and redressability: “I don't see a single item in your briefs that would satisfy our normal tests.”

The “temporal” link Aguiñaga tried to establish “just isn’t very good,” US Deputy Solicitor General Brian Fletcher argued in his closing rebuttal. Fletcher pointed out that a May 2021 email from Facebook to the government stated it had already taken action to remove health groups from its recommender systems. “It wasn’t reporting on something that it would do in the future, it was reporting on something that was already done,” Fletcher said. “It's not even clear from the email that Facebook was doing that because of any request from the government. It was a report of its own action.”

Related Reading:

- A Conspiracy Theory Goes to the Supreme Court: How Did Murthy v Missouri Get This Far?

- Backgrounder: Supreme Court to Hear Oral Argument in Murthy v. Missouri

- Podcast: What's at Stake in Murthy v Missouri?

As Tech Policy Press previously reported, the crux of the Murthy case centers around the Court’s potential willingness to determine the government’s ability to engage with social media companies on matters of public concern on the basis of questionable underlying evidence. A majority of the justices seemed concerned with this underlying issue, which has implications for whether the plaintiffs have standing to sue the government as well as if the government’s communications with social media companies were coercive.

Article III Standing

One of the main focuses Monday was on establishing plaintiffs’ Article III standing, which requires a party to prove they have both suffered as a result of the claims in a case and have a genuine stake in its outcome. The injury also has to be fairly traced back to the challenged action. If standing is established for even one plaintiff, the justices are required to rule on the merits of the case.

Justice Samuel Alito, in his line of questioning with the government’s counsel, argued that traceability is “a question of causation,” and seemed to accept the lower courts’ interpretation that the platforms’ actions against Hines were traceable to the government. “We don't usually reverse findings of fact that had been endorsed by two lower courts,” said Alito.

US Counsel Fletcher disagreed, arguing that the lower courts applied a loose notion of traceability and any injury Hines suffered was not a result of the government’s actions. “They [the lower courts] said the government is talking to the platforms a lot. The platforms are doing moderation. And so we'll just assume that all of that moderation is traceable to the government,” Fletcher told Alito.

Other justices were skeptical of the underlying evidence used as the basis of these traceability claims. “I have such a problem with your brief counselor. You omit information that changes the content of your claims. You attribute things to people who it didn't happen to,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said during a line of questioning with Solicitor General Aguiñaga. “I don't know what to make of all this, I'm not sure how we get to prove direct injury in any way,” Justice Sotomayor added. Solicitor General Aguiñaga apologized, taking “full responsibility” if the plaintiffs’ brief was “not as forthcoming as it should have been.”

Seeking further clarification on the discrepancies in the plaintiffs’ supposed smoking gun, Justice Sotomayor asked the government’s counsel if he knew exactly what was censored over the ninety days that Hines’ Facebook page was suspended.

“So that’s the problem. I don't think we do,” US Counsel Fletcher said. “One of the things that's hard is that there's not a lot of specifics about even the dates on when things happen. I guess I will say when the dates are provided, though, they don't line up.” Fletcher cited the RFK Jr. tweet example, flagging that the government statements Hines alleges led to Twitter’s moderation action in April 2023, were originally made between January and July of 2021 – or two years later, after Twitter was sold to Elon Musk and its COVID-19 moderation policies abandoned. “I think that's a strong indication that there's a real traceability problem,” Fletcher argued.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett also seemed ready to accept the government’s argument that the suit contained factual errors. In a back and forth with Fletcher, she noted that the lower courts appeared to conflate unrelated messages from the government – like US officials flagging to Twitter an account impersonating President Biden’s granddaughter – with “threats” to social media companies related to the pandemic and suppression.

Coercion vs. Persuasion

The justices also queried the plaintiffs’ characterizations of exchanges between government officials and social media executives, and whether they crossed a line. Consistent with their dissent in the Court’s stay of the modified injunction, Justices Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch showed some signs of being more sympathetic to plaintiff’s claims. In the underlying suit, plaintiffs allege that the government “significantly encouraged” platforms’ content moderation decisions, a framing the Fifth Circuit agreed with in its injunction. The legal test for ‘encouragement’ is articulated in Blum v. Yaretsky, a 1982 case in which the Supreme Court decided that the government can be held responsible for a private decision when it has exercised coercive power or provided significant encouragement to private actors.

Justice Thomas quickly dismissed the applicability of Blum’s state-action test to this case, asking US Counsel Fletcher to confirm that Blum is usually only applied to relationships regarding issues like Medicare or government contracts. “We don’t think it’s possible for the government, through speech alone, to transform private speakers into state actors,” Fletcher argued, while offering up a “Bantam Books-type framework” for the Court to evaluate claims of government coercion and persuasion.

In the Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan opinion, issued in 1962, the Supreme Court barred the government from coercing private speech intermediaries into suppressing disfavored speech while also implying that the First Amendment permits the government to attempt to persuade private actors. The Knight First Amendment Institute similarly asked the Court to use the coercion test in its December amicus brief. It argued that the Bantam test “is the correct way to analyze jawboning claims because it best accounts for the multiple First Amendment interests at stake.”

Justice Gorsuch, referencing other considerations in the Knight brief, noted that the concentration of powerful tech corporations—unlike the more fragmented media landscape—might have made coordination between government and private entities easier and thus a relevant factor for determining coercion. “Do we have to account for the possibility as well that in some circumstances, it [concentration] may make coercion easier?” he asked US Counsel Fletcher.

Justice Samuel Alito pushed the characterization of the parties' relationship even further, positioning them as “partners” rather than coordinating entities. Justice Alito, in reading “all of the email exchanges” presented as evidence, saw the federal government demanding immediate answers from their would-be partners at social media companies, and cursing them out when unhappy with the outcome. “There are regular meetings. There is constant pestering of Facebook and some of the other platforms and they want to have regular meetings, and they suggest rules that should be applied and why don't you tell us everything that you're going to do so we can help you and we can look it over,” said Justice Alito.

Under Justice Alito’s interpretation, the only reason for this behavior is due to the government having “Section 230 and antitrust in its pockets." He asked the government’s counsel, “do you think that the print media regards themselves as being on the same team as the federal government, partners with the federal government?” In response, Fletcher pointed out that the language of ‘partnership’ came from the platforms publicly stating they have a responsibility to give people accurate information and want to help the government achieve this goal.

Related Reading:

- First Amendment Defenders and the Supreme Court Should Reject the Jawboning Bogeyman

- Review of Amicus Briefs Filed in Murthy v. Missouri Before the Supreme Court

- Doctrinal Disarray: Amicus Briefs in Murthy v. Missouri and NRA v. Vullo Reveal How Divided Legal Commentators Are on Jawboning Questions

Justice Brett Kavanaugh directly disputed Justice Alito’s characterization, saying he assumed that experienced government communications staff regularly call the media to berate them. And later, during questioning with Louisiana Solicitor General Aguiñaga, Justice Kagan noted that the White House will regularly call up newsrooms like The Washington Post to say, for instance, that a story will harm national security if published – information they aren’t required to act on. This is a “valuable sort of interchange,” argued Fletcher, where newspapers know if their story puts lives at risk while still exercising their own editorial judgment.

Several justices, however, were concerned of the secondary effects a ruling could have on government speech writ large, especially with how expansive the lower court’s injunction was.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was critical of the legal standard recommended by the plaintiffs’ counsel. As a hypothetical, Justice Jackson asked Aguiñaga what the government should do if the latest online “teen challenge” involved teens jumping out of windows. Aguiñaga argued that, although the government could use its bully pulpit to recognize it as a public health emergency, it could not call the platforms directly. “The moment that the government tries to use its ability as the government and its stature as the government to pressure them [platforms] to take it down, that is when you're interfering with the third party's speech rights,” he said.

Justice Jackson pointed out that the government has a duty to take steps to protect its citizens and, in certain situations, can require that speech be suppressed if there’s a compelling interest. “You seem to be suggesting that that duty cannot manifest itself in the government encouraging or even pressuring platforms to take down harmful information,” she told Aguiñaga.

Even Justice Gorsuch, who generally appeared more sympathetic to the plaintiff’s case, had questions about the expansiveness of the injunction, which swept up non-parties into the enjoined actions. In an exchange with Aguiñaga, Justice Gorsuch expressed concern over the “universal injunction,” which he said the Courts have seen “an epidemic of” lately. “Normally our remedies are tailored to those who are actually complaining before us and not to those who aren't, right?” he asked the Solicitor General. Aguiñaga offered to limit the injunction to the five platforms and seven plaintiffs involved in the case, so long as the Court ruled in favor of plaintiffs on the merits.

The Supreme Court justices indicated that, despite much-needed clarification on the line between coercion and persuasion, and the potential impacts of a sweeping injunction that limits nearly all communications between the US government and social media companies, the outcome of Murthy v. Missouri may ultimately pivot on the question of standing. Establishing it should only require identifying a single piece of compelling evidence of harm clearly traceable to government action within the plaintiffs’ 20,000 pages of documents; but based on the oral argument, that might not be a sure thing.

Authors