State Mandated Social Media Warning Labels Open New Front in Battle Against Tech Companies

Gopal Ratnam / Jan 27, 2026

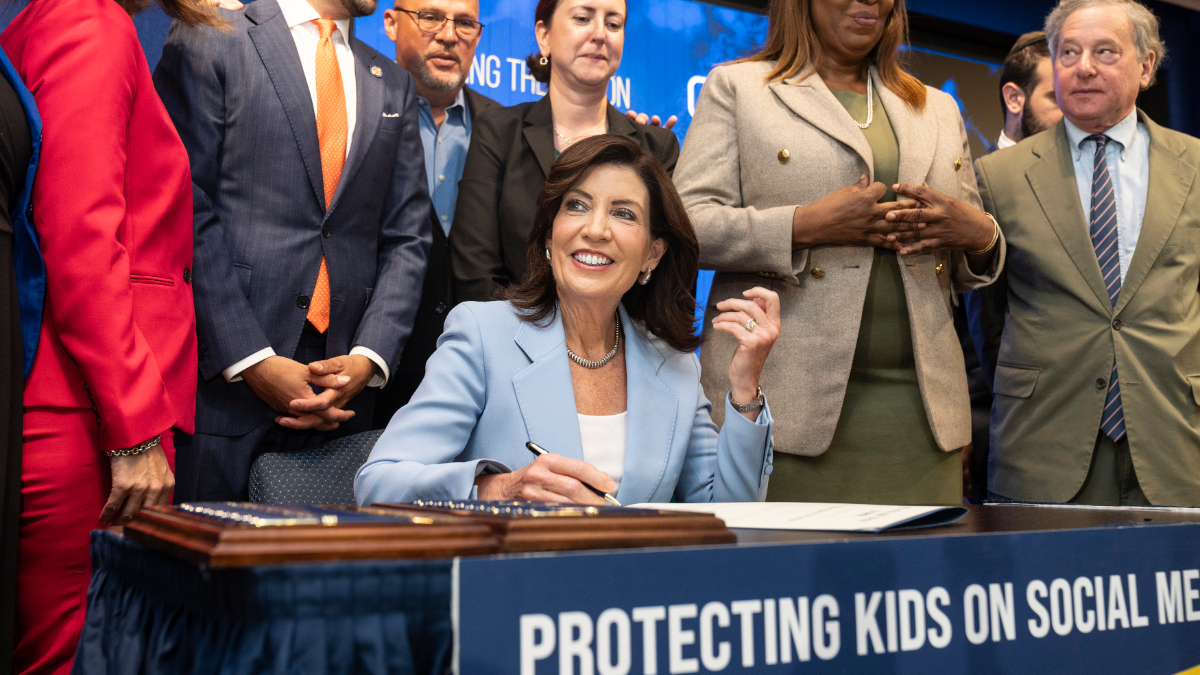

New York Governor Kathy Hochul (D) signed legislation to combat addictive social media feeds and protect kids at UFT Headquarters in New York on June 20, 2024. (Photo by Lev Radin/Sipa USA via AP Images)

Four American states have enacted laws requiring social media companies to place warning labels on their apps if they know that the user is a minor below a certain age, opening a new front in the battle between governments seeking to protect kids from online harms and tech companies’ seeking to expand their user base.

New York became the latest state to pass a legislation that was signed into law by Gov. Kathy Hochul in December. It follows similar measures in Colorado, Minnesota, and California. Texas also is considering a warning label law that passed in the state’s lower chamber in 2025 but has yet to be taken up by the Senate.

The Minnesota law is set to go into effect in July, with the California law slated to become effective starting Jan. 2027. The New York law doesn’t have a start date yet. After NetChoice, a tech industry group, challenged the Colorado law on First Amendment grounds, a US district court in November temporarily halted the law from becoming effective in January.

The state measures come after Congress has repeatedly failed to enact any type of legislation aimed at curbing what experts see as mental and physical harms posed to kids and adolescents from addictive features of social media apps. The state laws stem directly from former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s 2024 call for warning labels that he said would increase awareness of dangers and change users’ behavior.

“The warning labels are designed to educate both minors and parents about the mental health risks associated with social media use,” California State Assembly member Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, who sponsored the bill in the state, said in an email. “The data is clear and alarming: adolescents who spend more than three hours a day on social media face double the risk of anxiety and depression symptoms, yet average daily use among teens is 4.8 hours.”

Julie Frumin, a California-based therapist who advocated for the state’s legislation, said she sees patients in her practice who have suffered mental health harms because of excessive social media use.

“More than half of my caseload is young women who live their lives on these apps to be literally influenced and be harmed by them,” Frumin said. “I think a warning label is really important from a public health perspective because many individuals are just now coming into contact with the research showing that there’s a strong link between mental health problems and social media use.”

Even for young people who may have heard about the link between mental health and social media overuse, “it’s a powerful reminder like what you see on a cigarette box or in a parking garage warning about the dangers” of smoking, Frumin said.

State lawmakers and Murthy have compared the warning labels to graphic warnings on cigarette packs, which they say has been effective at increasing awareness about the health dangers from tobacco use and has led to behavioral changes.

In a June 2024 op-ed in the New York Times, Murthy cited evidence from tobacco studies showing “that warning labels can increase awareness and change behavior.” Murthy also cited a survey conducted by the Omidyar Network on social media and mental health issues among Latino youth that found that 76 percent of survey respondents said they would “limit or monitor their children’s social media use” if the surgeon general were to issue a warning about the dangers of using such apps. (The Omidyar Network has provided grant funding to Tech Policy Press.)

Murthy cited research showing that prolonged use of social media apps by kids and adolescents below the age of 18 results in body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, low self-esteem, sleeping difficulties, depression and suicidal ideation. Kids also are exposed to hateful content on some of the apps, he said.

A randomized clinical trial in 2021 conducted by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and others, found that while graphic warning labels on cigarette packs “decreased positive perceptions of cigarettes,” and resulted in smokers quitting in the short-term, it “did not affect cigarette cessation or consumption levels.”

The California law is among the most prescriptive on what the social media label should say. It would require social media companies to display to users below the age of 17 for every calendar day they log into an app a “black box warning” taking up at least one-fourth of a screen’s space that “displayed clearly and continuously for a duration of at least 10 seconds, unless the user affirmatively dismisses the warning by clicking on a conspicuous X icon.”

The label would say, “The Surgeon General has warned that while social media may have benefits for some young users, social media is associated with significant mental health harms and has not been proven safe for young users.”

Under the California law, after a minor user has spent more than three hours on an app, the black box warning label would get larger and would take up 75 percent of the app’s screen or window and would be displayed continuously for 30 seconds without an option to click through. Every hour thereafter the warning label would reappear.

Parents of teenagers suffering mental health problems also are suing tech companies in courts. The first high major case against Meta, TikTok, and YouTube goes to trial this week at the Los Angeles County Superior Court. The case is centered on a young girl who alleges that she suffered anxiety and depression because of using several social media apps throughout her childhood.

Tech company CEOs have reassured lawmakers that they’re taking steps to protect kids and minors online after Congress has summoned the executives on multiple occasions following whistleblowers raising alarms about inadequate safety measures.

But the CEOs’ actions fall short of their assurances, said Holly Grosshans, senior counsel for tech policy at Common Sense Media, a nonprofit group that focuses on kids’ safety online. The group has backed warning label legislation in California, Colorado, and New York.

States had no option but to act on warning labels because “we are constantly hearing from these companies and these CEOs when they come testify before Congress, and they're constantly issuing statements about these parental tools that they're rolling out, or how safe these products are,” Grosshans said. “And the fact of the matter is, they're not safe. They have not been declared safe. They cause addiction to these products. And we just want to make sure that people are warned of that.”

In December, Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, said it had revamped its Instagram Teen Accounts “inspired by movie ratings for ages 13+,” as a safety feature. “This means that teens will see content on Instagram that’s similar to what they’d see in an age-appropriate movie.”

Congress also has tried and failed thus far to enact legislation that would protect kids and minors from online harms.

But in December, the Republican-led House Energy and Commerce subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing and Trade, took a key step in advancing a package of 18 bills relating to kids safety online. Still, the measures face opposition from Democrats who say the bills include broad preemption language that would prohibit state tech legislation.

The package did not include another measure backed by Sens. John Fetterman (D-PA) and Katie Britt (R-AL) called Stop the Scroll Act, which would require social media companies to display warning labels on apps about mental health. The measure was reintroduced in the current session after failing to gain traction in the last session of Congress that ended in 2024.

“The label would appear in a pop-up format each time a user opens the app or site, with language warning of the potential mental health harms associated with extended use,” the senators said in a statement last year. “Users would have to acknowledge the warning before proceeding. The warning could not be obscured, altered, or hidden in any way.” The Federal Trade Commission would enforce the law.

The state warning label laws also face legal and likely technical challenges, according to industry groups and experts who study the effectiveness of warning labels, especially on digital products.

NetChoice, a trade group that represents Amazon, Google, Meta, and others, has temporarily succeeded in stopping the Colorado law from taking effect by arguing that requiring companies to place warning labels violates the Constitution's protection that “prevents the government from imposing its views on private actors.”

“It's disappointing to see these states approve censorship labels on lawful speech in America,” Amy Bos, vice president of government affairs at NetChoice said in an email. “As we've seen in our case against Colorado, these misguided new laws ignore established constitutional protections against mandates for government-dictated warning labels on speech and substitute political mandates for the evidence-based solutions that parents and families truly need.”

A spokeswoman for NetChoice said the group has no immediate plans to sue other states that have enacted similar warning label laws.

Experts who have studied warning labels said that labels by themselves are unlikely to yield results that advocates are seeking in the case of social media overuse.

“As far as I know, telling people this could be dangerous is not a very effective way of helping them to regulate” their use, said Rachel Rodgers, associate professor of counseling psychology, at Northeastern University.

Teenagers already are likely to be aware of data and studies showing that excessive use of social media could be harmful and “therefore this is not new information,” provided by warning labels, Rodgers said.

Unlike social media apps that are digital products, the effectiveness of warning labels on a physical product like cigarettes is likely enhanced by other restrictions such as limiting the public spaces where people could smoke, Rodgers said.

“We have a lot of experimental data saying that these types of labels do not work,” especially in the digital realm, Rodgers said.

In 2017 France passed a law requiring warning labels on ads in which the models whose shape and weight were digitally altered, Rodgers said. The goal was to reduce social effects stemming from people comparing themselves to such digitally altered images, she said.

“But these images continue to be used as a source of appearance comparison,” Rodgers said.

In the case of tobacco warning labels, advocates had to demonstrate in lawsuits challenging such labels that tobacco use did cause cancer and it’s likely that in addition to First Amendment challenges, the social media warning labels also would likely face similar tests in establishing that overuse of social media does result in mental health harms, said Wendy Parmet, law professor and director of the Center for Health Policy and Law at the Northeastern University.

Unlike a physical product like a cigarette, it may be harder to pin down exactly what social media is because “the algorithms [underpinning the apps] are changing every week,” Parmet said. The science behind tying social media use to mental health harms “is always one step behind the changing algorithms.”

Advocates of warning labels acknowledge that the labels by themselves are unlikely to address the mental health challenges faced by teenagers.

“While warning labels alone won't make social media safe, they are a continuation of efforts here in California to ensure kids are safely engaging in social media use,” California lawmaker Bauer-Kahan said in the email.

Efforts to enact laws requiring tech companies to develop age-appropriate software codes, educating parents and teenagers on social media use are part of the broader effort, Bauer-Kahan said.

Authors