Social Media Platforms are Silencing Social Movements

Amarnath Amarasingam, Thusiyan Nandakumar / May 14, 2021Social platforms are censoring Tamil activists, argue Thusiyan Nandakumar, an editor at the Tamil Guardian and Amarnath Amarasingam, a professor and extremism researcher at Queen's University.

Rights groups and activists have long complained that social media platforms are taking down content that is integral for human rights activism around the world. This has ranged from deleting evidence of chemical weapons attacks in Syria, to suspending some accounts linked to the farmer’s protest in India, and, just this week, removing content highlighting the violence in Sheikh Jarrah. Some of these removals seem to be happening by accident and are reinstated shortly after, while others are driven by mass reporting by digital activists working for various authoritarian governments.

There are numerous instances when social media posts highlighting injustices, commemorating the dead, and even basic news stories linked to the plight of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka were removed by social media companies. The armed conflict in Sri Lanka came to an end in May 2009, and every year on May 18, the Tamil community globally commemorates and remembers the tens of thousands killed in those final days. The United Nations Human Rights Council has accused Sri Lanka of “obstructing accountability” and has committed to monitoring ongoing human rights violations in the country. By repeatedly removing activist content, legitimate news stories, and posts remembering the war dead, social media platforms are helping to silence voices for human rights.

In February 2021, the hashtag #GenocideSriLanka was trending on Twitter in Toronto, London and Paris, as part of a social media campaign by Tamil diaspora activists to draw attention to the plight of the ethnic group in Sri Lanka. The campaign, which saw hundreds of thousands of tweets being sent, was successful in garnering mainstream media coverage and shedding light on Sri Lanka’s human rights record. Yet, despite the ability to mass mobilize on Twitter, Tamil activists faced another set of barriers on other social media platforms.

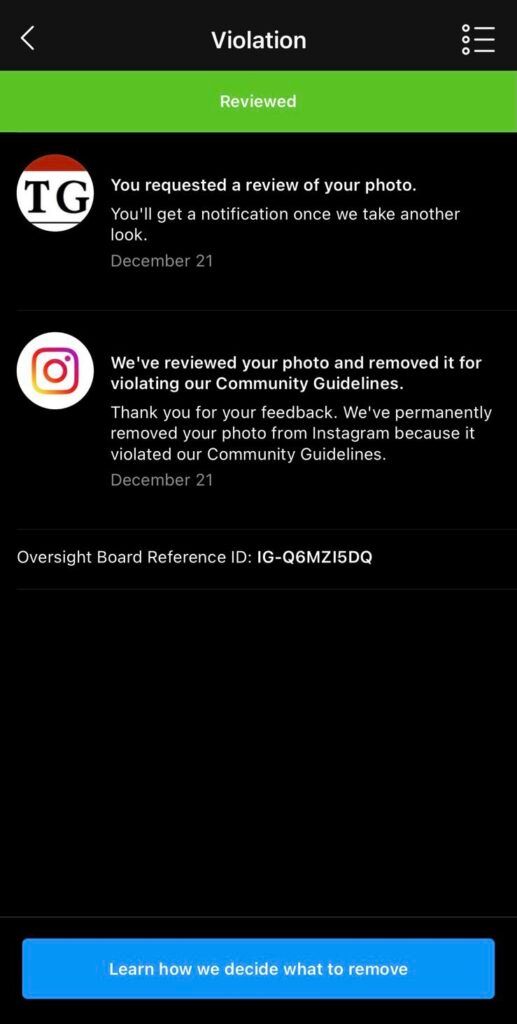

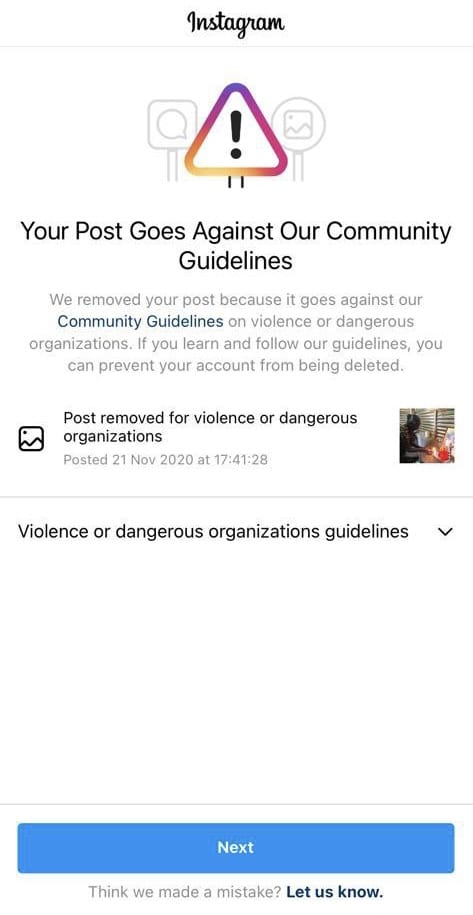

For several years, users of Facebook and Instagram have reported that content discussing Tamil demands for self-rule, the history of Tamil militancy and even human rights on the island were being repeatedly removed by these platforms. Most often posts were apparently deleted due to what Facebook has termed a breach of their Community Standards, particularly with regards to “dangerous and violent organisations”. In recent months, we have observed the removal of such content has been ramping up with hundreds of posts being taken down - sometimes just minutes after being posted.

Artwork of a flower. Posted by @tamilguardian. Removed from Instagram in November 2020.

The impact of this broad and blunt censorship has been wide ranging, effectively silencing a crucial aspect of social movements online. News articles covering events on the island, historical photographs documenting Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict and even political artwork have all faced removal. Not only has this stunted discussion around the legacy of Tamil militancy and the continued struggle for justice and accountability on the island, it has effectively strengthened the Sri Lankan state’s authoritarian approach to clamping down on freedom of expression.

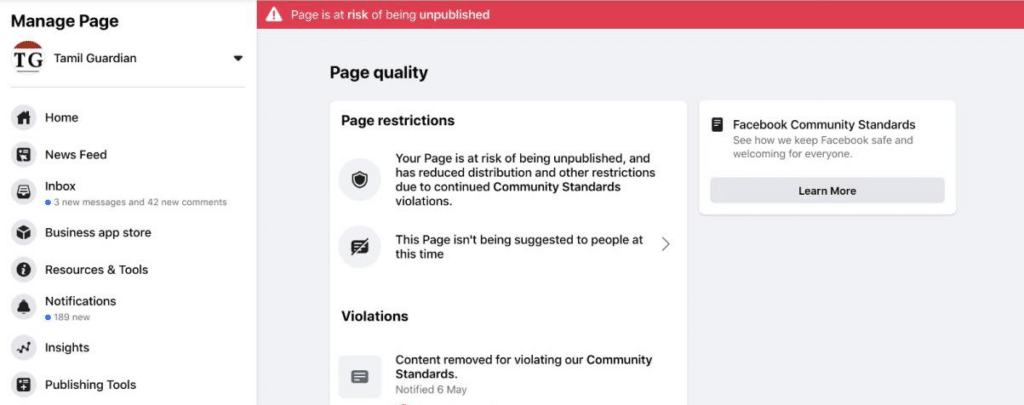

The Tamil Guardian, a London-based newspaper that has been reporting on Tamil and Sri Lankan affairs for over 20 years, is one such outlet that has been hit by this policy. Its accounts on Facebook and Instagram appear to have been ‘shadowbanned’ and are now at risk of removal entirely, for what have been deemed repeated violations of Facebook’s ‘Community Guidelines’ when covering current affairs in Sri Lanka.

This comes despite the outlet continuing to post freely on Twitter and other platforms, with content never having been flagged or removed elsewhere. The newspaper has also never been accused of breaching any laws in the United Kingdom with regards to proscribed terrorist organizations or concerns ever having been raised by British authorities. Yet, dozens of posts have been removed in recent months, an occurrence that has become familiar to other Tamil journalists and activists who post on social media. Attempts to raise these concerns through both Instagram and Facebook’s feedback tools have failed and the removals have continued, recently increasing in both scope and frequency.

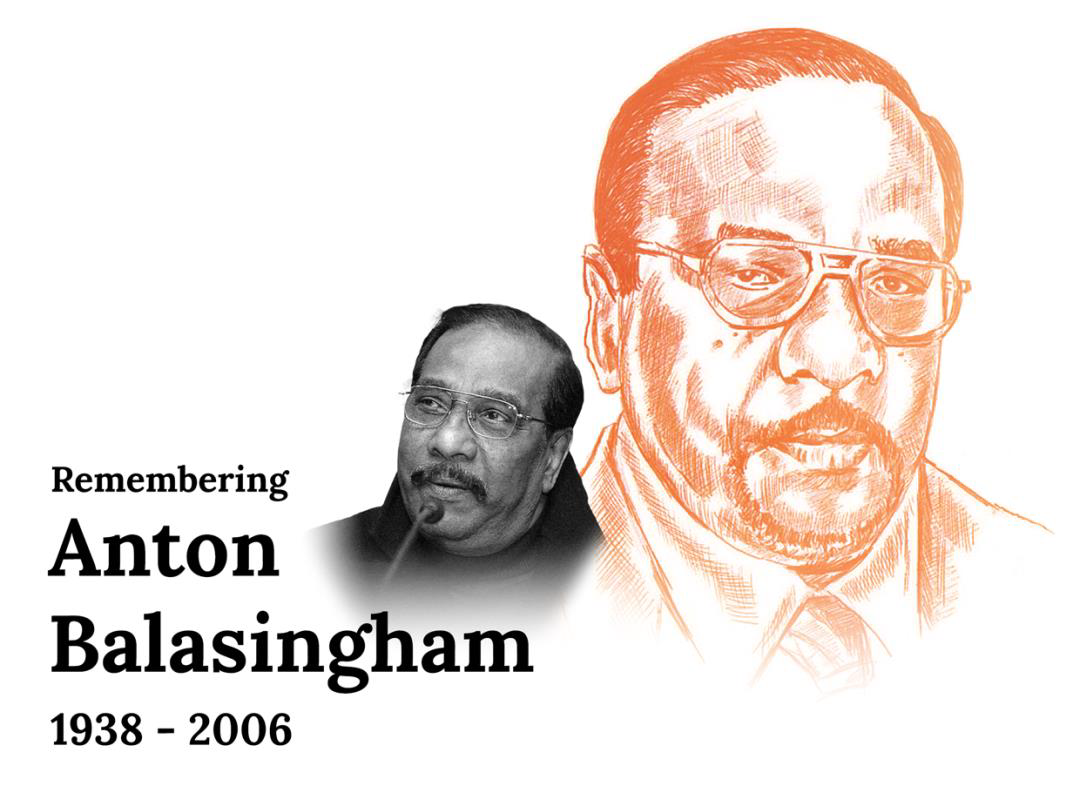

A graphic of Anton Balasingham, the chief negotiator and political strategist of the LTTE. His passing was marked by obituaries in The Times of London and The Guardian amongst many others. Posted by @tamilguardian.

Removed from Instagram in November 2020.

Typically, any posts that mention the history of Tamil militants, particularly the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), risk removal. The armed movement was militarily defeated in May 2009, when Sri Lankan security forces concluded a wide scale offensive that killed tens of thousands of Tamil civilians and has since been the subject of several UN reports and resolutions. To date, there have been no credible reports of organized LTTE activity on the island for more than a decade. However, posts that examine or report on the LTTE face an almost blanket ban, even if taking a critical view of the organization. Amongst posts that have been deleted are those that mention dead LTTE cadres, still living or disabled former fighters, photographs or sketches that may feature LTTE uniform, a mention of the terms ‘LTTE’ or ‘Tamil Tigers’ in captions, and even the publication of quotes from deceased LTTE figures. This is despite attempts at media coverage of events such as LTTE uniform being found in mass graves, or of articles on LTTE leaders who have had obituaries in other mainstream press.

Removal notices sent to the Tamil Guardian, courtesy Thusiyan Nandakumar

The censorship however goes wider than just Tamil militant organizations. Reporting on Tamil remembrance ceremonies that have taken place in both Sri Lanka and around the world have frequently faced removal. Remembrance events and commemorations continue to play a major role in Tamil politics, with Tamils around the world regularly commemorating their war dead.

In the UK and North America, for instance, large scale events are usually held with tens of thousands of people in attendance and with members of parliament and other lawmakers frequently addressing the crowds. Tamil nationalist imagery is often on display, including the Tamil Eelam flag - a symbol of the aspirational independent state that many still advocate for, the karthigaipoo (the flame lily) flower, photographs of the dead and of cemeteries and tombs. Sri Lanka’s Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms, which had a mandate from the Sri Lankan government, also reiterated the importance of the right to collective memorialization of those who died in the war, including LTTE cadres. Ultimately, even in Sri Lanka, there is no ban on remembering those who died, including LTTE cadres. Yet on Facebook and Instagram, it seems there is.

A photograph of a destroyed LTTE cemetery. Posted by @thusiyan linking to an article here. Removed from Instagram in November 2020.

Australia’s New South Wales MP Hugh McDermott at a remembrance event in Sydney. Posted by @tamilguardian. Removed from Instagram in July 2020.

This increase in censorship on these platforms takes place at a particularly difficult time in Sri Lanka. Former defense secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa returned to power as president in 2019, cracking down on dissenters and jailing journalists. His previous tenure, which saw several media workers murdered, speaks for itself. The US State Department and Reporters Without Borders are amongst the many to have voiced concern about freedom of expression on the island, with Sri Lanka remaining 127th out of 180 countries on the RSF World Press Freedom Index. Recent months alone have seen civilians and journalists who have shared posts on social media, including Facebook, arrested by the Sri Lankan security forces under terrorism charges. In 2019, the head of Sri Lanka’s army Shavendra Silva labelled “threats” from social media posed “serious concerns for national security”. The general went on to compare “misguided youths sitting in front of the social media” to suicide bombers, just weeks before Rajapaksa would take office and a renewed crackdown on freedom of expression was to begin. Silva himself remains barred from entry to the US over his role in overseeing war crimes.

While the silencing of Tamil activism on these platforms is frustrating, and likely to ramp up again as the community commemorates the war dead next week, it is a problem impacting activists from India to Palestine. Social media platforms need to do better to ensure that activist voices aren’t silenced at the precise time they need to be amplified, and do not unwittingly aid authoritarian regimes trying to clamp down on criticism.

Authors