Silicon Valley Must Not Silence Kashmir

Ifat Gazia / May 24, 2021Have you ever received emails from Twitter, asking you to find legal counsel because your account has been flagged by a nation’s government and security services? The experience can be pretty unsettling. It gets more unsettling when these emails become a regular occurrence and you have no idea how to deal with them. In my case, I ignored these messages until, one day, my Twitter account was suspended.

I am Ifat Gazia, a Kashmiri Muslim, doing a PhD degree in Communications at the University of Massachussetts, Amherst. I am a podcaster, a filmmaker and as a scholar, I study exactly this: how and why big tech platforms like Facebook and Twitter stifle minority and dissident voices at the behest of the governments they criticize. And despite my background, when Twitter’s censors came for me, I had no idea what to do.

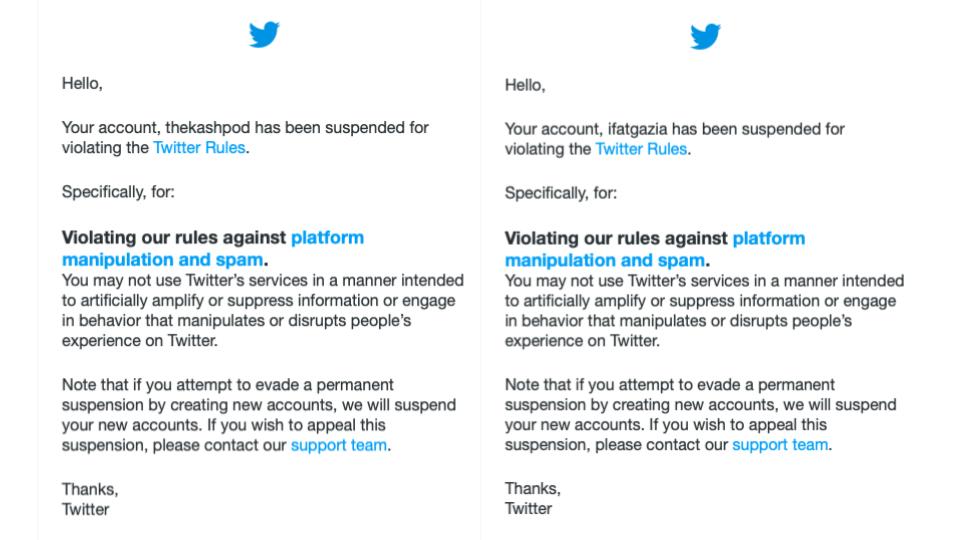

On March 23rd this year, both my personal Twitter account and The Kashmir Podcast account were suspended. This did not come as a shock: the Twitter accounts for influential activist group Stand with Kashmir and other Kashmiri advocacy and activism accounts were suspended some weeks before. Emails from Twitter stated that the suspension occurred because my tweets engage in platform manipulation and spam. To be clear, I neither spam nor manipulate the platform: my Twitter feeds are opinionated but informative. So why have I become persona non grata to Twitter?

Simply put, Kashmiri accounts like mine get mass reported by right-wing Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) trolls and Twitter has no mechanism in place to validate or investigate these false reports. Like most social media websites, Twitter relies on user reports to identify abusive behavior. These mechanisms are easily manipulated. When a group of users want to harass or silence voices they don’t like, they work together to report content they want to silence. Some platforms refer to this behavior as “brigading”. It is better understood as user-based censorship or harassment. And it works.

The day of my suspension, a friend of mine shared a screenshot with me. It was a tweet from an account that claimed responsibility for getting my accounts suspended. That tweet referenced my accounts as "case numbers" and also openly congratulated its "team" for successfully brigading my accounts and getting them suspended.

Examining other posts from this account's timeline makes it clear that it is dedicated to brigading accounts targeted by Hindutva supporters. It claims to get more than ten accounts suspended every day. My friends and allies all reported the account to Twitter. Nevertheless, it is still active, brigading accounts, getting thousands of likes and tweets.

I experienced the new realities of attacks on Kashmiris when I began receiving emails from Twitter, telling me my accounts were going to be suspended. Twitter told me that it had received communication from the Government of India ordering it to pull down my personal as well as my podcast account because my “tweets violate India’s Information Technology Act, 2000”.

All of my tweets were informative and shared with the outside world what is happening in Kashmir. Many link to international news reports. Some of the tweets the Indian government objected to even included informing my audience when the next episode of the podcast was going live.

As a Kashmiri, I am not surprised at the lengths that the Indian government will go to in silencing dissident speech. But it is absolutely shameful that Twitter, a platform that claims to support freedom of expression, can be complicit in the suppression of voices critical of the Indian government. Twitter sometimes even acts directly at the behest of Indian government- for example, just last month it deleted 50 tweets that were critical of the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Understanding the situation in Kashmir

Since 1947, the region of Jammu and Kashmir has been under Indian occupation. For two years in the 1960s, Pakistan sought to claim Kashmir, leading to a border war between India and Pakistan. Indian troops, in place since 1947, reinforced their positions to defend the region and even today, Kashmir remains the most militarized place in the world.

In August 2019, the Indian government, led by the Hindu nationalist prime minister, Narendra Modi, abrogated the region’s special status which had allowed local residents protections over residency, land, and employment rights. This step raises fears in Kashmir and beyond that Indian is working to destroy Kashmir’s independent identity. Much as minority ethnic groups in China worry that government-sponsored mass migration of Han Chinese to their regions will destroy their cultural identities, Kashmiris worry about the transformation of their homeland.

Part of the occupation of Kashmir has been a blackout of online speech. Kashmir has experienced the longest internet blockage ever enforced in a democracy. For seven months of 2019-2020, the Indian government cut internet and phone connectivity to Kashmir, eventually restoring slow, 2G connectivity but limiting access to a whitelist of permitted internet sites. The Indian government cited concerns over terrorism to justify the blackout, but the net effect has been plunging more than eight million people into a pre-internet age, and to dividing families and friends from Kashmiris in the diaspora.Even now, mobile internet is regularly suspended during “encounters” between the Indian Military and Kashmiris. Since 2012, 305 internet shutdowns have been reported from the Kashmir region.

Silencing the Diaspora

Attempts to silence Kashmiris in the diaspora appear to be the next phase of the online conflict. Mass reporting of Kashmiri Twitter accounts or direct suspension by Twitter has lately become very common. Since January 2021, the account for Stand with Kashmir was suspended twice and so were the accounts of dozens of Kashmiri activists and academics.

For many Kashmiris, social media provided a space where they could share their stories with the world. Importantly, social media is also the space where we can raise awareness of the situation in Kashmir. Kashmiris have always been vocal about the injustices happening in other parts of the world, showing solidarity with other subjugated people like the Palestinians. What is sad is most people in the world don’t even know where Kashmir is.

To lift the veil of silence and miseducation around Kashmir, I started my podcast in 2020 to bring to the world the stories of Kashmiris, to show people what living under occupation really looks like. The first season of our podcast was released in 2020 and had nine episodes talking about pressing issues and themes. We had guests talking about occupation, human rights, education, journalism, disappearances, torture, and gender.

Efforts like my podcast became especially important as India embarked on settler-colonial policies that seek to make the Muslim-majority region into a Hindu majority- a policy of forced demographic change that very few in the international community have raised their voice against.

Despite the length and intensity of conflict in Kashmir, the international community barely knows what happens in the Muslim majority region. Oddly enough, the silencing of Kashmiri voices seems to be one of the few issues that attracts mainstream media attention to Kashmir. According to news index Media Cloud, the reportage on Kashmir especially increased after August 5th, 2019 when the Hindu nationalist government in India not only revoked the region's autonomy, but also pushed a population of more than eight million into a complete communication blackhole. While any attention to Kashmir is appreciated, attention to the region during a communications blackout is ironic - it’s Kashmir without Kashmiri voices from the ground.

Leaving home and speaking out

I was last in Kashmir in August, 2019. On Sunday night, August 4th, a doctor friend of mine called me saying we should buy any essentials, as she heard rumours that there might be a curfew starting Monday. Curfews in Kashmir are not unusual, but what made this one particularly scary was that thousands more military men were flown into an already heavily militarized region. Indian tourists, pilgrims and students were asked to either leave Kashmir or were evacuated.

On Monday morning I woke up to a pin drop silence. Nothing was moving on the roads and our mobile phones could no longer find a cellular network. It felt like life had completely stopped. We were lost, as if we didn’t exist on the map of earth anymore. Television only showed selected news channels that peddledIndian government narratives. Ten days later, I made a tedious journey to the airport where there were hardly any Kashmiris, but still more military personnel being flown in. I remember my husband whispering to my ear, “We will never return back to the same Kashmir again”.

I landed in the US and for seven months to come, I communicated with my family through third parties. Some landline telephones were restored in Kashmir later in August, but I was not able to call them from the US. Ironically, after mobile phones were introduced in Kashmir in the late 2000’s, people cancelled their landline subscriptions. There are barely any families that still have a landline. I would call a Kashmiri friend in another part of India, they would call that landline number and if I got lucky, one of my family members would be around and I could leave a message for a minute or two. It was in February 2020 when 2G internet was restored in Kashmir and I saw my parents on a hazy 2G video call. In all those months, my resolve to fight to overcome the injustices Kashmir has suffered only grew stronger.

I am not alone in trying to call attention to Kashmir from the diaspora. Since 2019, the Kashmiri diaspora has been an increasingly vocal presence, calling attention to the situation in their homeland, as they are able to communicate with the wider world, while domestic Kashmiris are often unable to share experiences from the ground. A number of individuals and organizations have been attempting to bring attention to what is happening in Kashmir in various spaces--Congress, colleges, communities, and the media. It is difficult work given the small numbers of the Kashmiri diaspora, as well as the very effective and well-resourced pro-India lobbies. My podcast in particular is in collaboration with Stand with Kashmir. SWK is led by young professionals in the Kashmiri diaspora in the US, and is committed to standing in solidarity with the people of Kashmir in ending the Indian occupation of their homeland and supporting their right to self-determination. Since Feb 2019, and especially after August 2019, they have been active in raising awareness and building solidarity with other social movements.

However, Kashmiris in the diaspora are not immune to censorship. SWK’s work has been massively targeted by the Indian government- its website is not able to be viewed in India and Kashmir, and its Facebook and Instagram accounts are not accessible either. Its Twitter account has been suspended twice- the second time for over a week. Despite these barriers to communication put up by the Indian government- with the cooperation of big tech companies- its work persists, in part because it is so difficult for Kashmiris at home to speak out.

Most of the Kashmiri human rights activists and journalists have self-censored themselves in recent years to ensure their own safety. After August 5th 2019, for months, Kashmiris were completely off the grid- no internet, mobile phones, or even landlines. Eventually, communication was restored and the Indian government “allowed” 2G internet, which is so weak that Kashmiris were barely able to attend online classes, especially during the pandemic. Most Kashmiris are also wary of using social media because of surveillance. Anyone who is critical of the situation in Kashmir is silenced by being detained, harassed, or tortured.

Now attacks against Kashmiri social media users and advocacy groups or individuals appear to be escalating. US-based social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have taken actions on accounts on Kashmir, often at the request of the Indian government, to silence them- much as they briefly silenced me. I was lucky- not only did many people raise their voices against my account suspensions, some even helped me to communicate with Twitter to get my accounts back. However, that is not the case for everyone.

Kashmir has been silenced for too long. In the past three decades, more than 70,000 Kashmiris have been killed and scores have been injured or arrested in Indian military crackdowns against all forms of Kashmiri resistance. Since the Partition of the Indian subcontinent, and Kashmir’s disputed accession to India, the Muslims of the region have been demanding their right to self-determination via a referendum or plebiscite. Most Kashmiris demand azadi- or freedom- from Indian rule. However, India has consistently, and many times violently, suppressed Kashmiri demands for freedom. Activists in Kashmir have long decried the many human rights abuses of the Indian government in Kashmir, which include extrajudicial killings, fake encounters, sexual violence, torture, and enforced disappearances. It is no wonder the Indian government wants Kashmiri voices silenced: the tale we have to tell is a grim and brutal one.

But it is intolerable that American-owned digital platforms are active participants in this silencing of Kashmiri voices. Big tech platforms must stop catering to the demands of authoritarian governments. They need to work with groups who are targeted for harassment, censorship and repression, and develop transparent mechanisms of accountability. They should have individuals or teams that are primarily focused on addressing such issues of suppression of dissident voices. They must stop giving false reasons for why accounts are suspended or censored. They need to put systems in place that can recognize when accounts are being mass-reported by bots or right-wing groups. If they hire human moderators to do the job, these moderators should be well versed in all social justice issues, including Kashmir.

What’s happening to Kashmiris online has happened to other groups - notably, the Rohingya in Myanmar. It’s a situation that demands the world’s attention, no matter who is being silenced. But Kashmir especially demands our attention because it’s a situation under-covered globally- we know about Kashmir only when Kashmiris are able to speak online. If Kashmiris are silenced- by the Indian government, by Hindu nationalist trolls or by tech platforms- one of the world’s oldest ongoing conflicts is destined to remain invisible.

Authors