Senators Propose a Licensing Agency For AI and Other Digital Things

Anna Lenhart / Aug 3, 2023Anna Lenhart is a Policy Fellow at the Institute for Data Democracy and Politics at The George Washington University. Previously she served as a Technology Policy Advisor in the US House of Representatives.

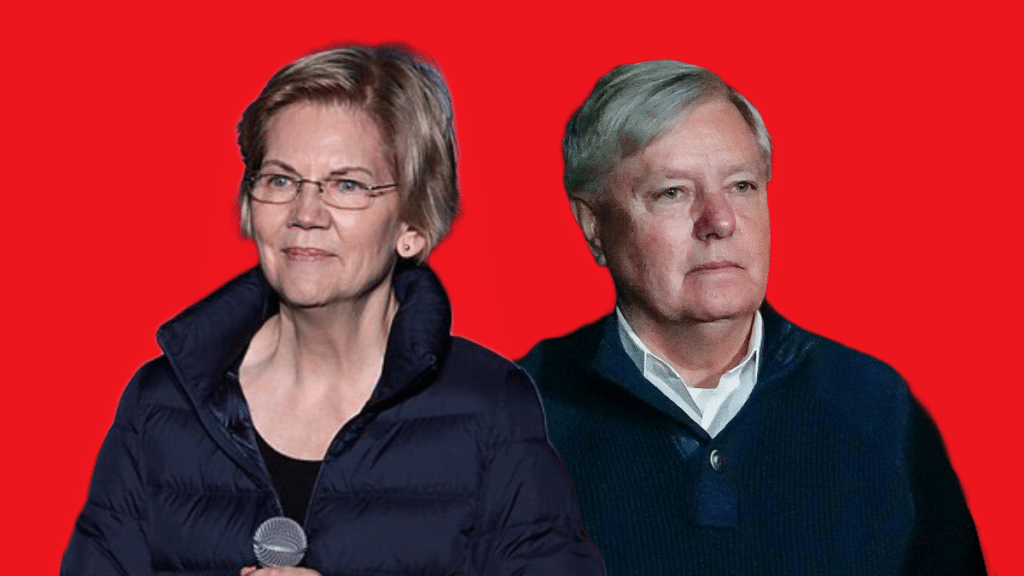

On July 27th, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) introduced the Digital Consumer Protection Commission Act of 2023. The 158-page proposal would create a new federal agency, structured as a commission, to “regulate digital platforms, including with respect to competition, transparency, privacy, and national security.”

The scope and provisions of the law are vast and span competition reform, transparency of content moderation decisions and data protections. Many of the policies are similar to ideas from previous legislation, with the notable exception of Title VI which creates an Office of Licensing for Dominant Platforms. Licensing, or the idea that products should be reviewed or certified before entering the consumer market, is not new. AI ethicists have discussed an “FDA for AI” for as long as I have been working in the field, and the idea attracted renewed attention from OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and NYU professor Gary Marcus at a May Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing. But the proposal from Senators Warren and Graham is the first outline for such an agency.

How would it work?

First, it's important to mention that only dominant platforms defined under Title 1, Subtitle B would need to obtain a license to operate. The definition of dominant platform is quite broad (see below), and includes platforms over a certain size (determined by monthly active users and net annual sales). While part C will likely include generative AI tools, the definition also captures large social media sites and ecommerce platforms.

“The term ‘platform’ means a website, online or mobile application, operating system, online advertising exchange, digital assistant, or other digital service that—

(A) enables a user to—

(i) generate content that can be viewed by other users on the website, online or mobile application, operating system, online advertising exchange, digital assistant, or other digital service; or

(ii) interact with other content on the website, online or mobile application,operating system, online advertising exchange, digital assistant, or other digital Service;

(B) facilitates the offering, sale, purchase, payment, or shipping of products or services, including software applications and online advertising, among consumers or businesses not controlled by the website, online or mobile application, operating system, online advertising exchange, digital assistant, or other digital service; or

(C) enables user searches or queries that access or display a large volume of information.” (Sec. 2002)

Dominant platforms are required to get a license once they hit the designation described in the bill, and on an annual basis the CEO, CFO and CIO of the dominant platform operator “shall jointly certify to the Office” that the platform is in compliance with other rules and mandates outlined in the bill. The Office can also revoke licenses if the dominant platform has “engaged in repeated, egregious, and illegal misconduct” that has caused harm to users, employees, communities, etc. and has not undertaken measures to address the misconduct (see Sec. 2603).

It is worth taking a deeper look at the rules and mandates required to maintain certification (there are dozens, I will highlight a few). First, Title II requires dominant platforms provide notice and appeals for content moderation decisions, for generative AI tools this could potentially mean disclosures to users when prompts are blocked. Notably, the Digital Consumer Protection Commission Act is missing a comprehensive approach to transparency, as it does not require that platforms publicly disclose details regarding their training data or mandate researcher access. The investigative authorities, however, provide staff within the commission with sweeping access for monitoring (Sec.2115). Additionally, the interoperability and portability mandates could open the door for more data transfers, donations and insights.

Title III prohibits self-preferencing and “tying arrangements” that require the purchase of one product or service to take advantage of another. For example, the Commission may determine that applications using Google’s LLM should not be designed to work faster on an Android operating system (self-preferencing) and/or Google can not require customers to purchase a suite of cloud services before accessing their LLMs (tying). Title III also prohibits dominant platforms from maintaining or creating a platform conflict of interest, meaning Google, Amazon, Microsoft may be required to spin off their respecting cloud infrastructures (along with other services) altogether (because, by analogy, landlords competing with their tenants is a conflict of interest).

Title IV outlines an extensive set of data protection provisions including a duty of care, specifically a covered entity (take note of the subject, I’ll circle back to this in a moment) cannot design their services “in a manner that causes or is likely to cause…physical, economic, relational or reputation injury to a person, psychological injuries…discrimination” (Sec 2412). In addition to the duty of care, covered entities must mitigate “heightened risks of physical, emotional, developmental, or material harms posed by materials on, or engagement with, any platform owned or controlled by the covered entity.” While not explicit, these provisions suggest risk assessment and mitigation practices touted by many AI policy advocates.

What about platforms that are too small or unprofitable to reach the dominant platform definition?

This is where things get interesting, especially in the generative AI context. Most of the provisions in the bill only apply to dominant platforms, with the exception of Title IV Privacy Reform, which has no size requirement and thus applies to any covered entity. In practice this means that while smaller for-profit operators of generative AI tools would not need a license to operate they would still need to follow the privacy reform protections including duty of care and mitigation. For providers of generative AI tools that operate under a non-profit model, which is not uncommon in the open source community, the text is a bit unclear. Specifically, while the covered entity definition lists operators subject to other laws such as the FTC Act, the challenge is that even the FTC does not have full jurisdiction of nonprofits. This is why comprehensive privacy bills such as the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) often add the following language to the covered entity definition:“is an organization not organized to carry on business for its own profit or that of its members.” As the business models for generative AI tools emerge, it will be important to scrutinize these definitions more closely.

Business model and sizing definitional challenges are one reason many proponents of licensing agreements prefer a risk-based approach to pre-market approval as opposed to size-based tiers. A risk-based approach requires defining a subset of technologies involved in high risk processes (hiring decisions, facial recognition, etc) and mandating that tools and services involved in those processes be pre-approved. A common critique of risk-based certification schemes is that they can be a barrier for new entrants into the market, and thus hinder competition.

While the Warren/Graham proposal’s lack of risk classification makes my eyebrows furrow, the current structure addresses competition concerns by limiting licensing to dominant platforms and prohibiting “abuse of dominance.” I have not decided where I come down on licensing. As someone with health problems, I am grateful that drugs and medical devices have to be pre-approved before entering the market. But online platforms span an endless combination of sectors and use cases, so truly assessing their risks requires subject matter expertise from across the federal government and ongoing engagement with an ever changing socio-technical system. These challenges separate these systems from products of the past. With that said, I commend the Senators for a major contribution to this conversation, and look forward to future Congressional proposals on this topic.

Authors