Senate Report on January 6 Points to Need to Investigate Role of Social Media in Insurrection

Justin Hendrix / Jun 9, 2021In its decision last week on whether to reinstate Donald Trump on its platform, Facebook rejected, in part, the recommendation of its Oversight Board to start a new internal investigation into its role in the insurrection at the US Capitol on January 6. The company said, “elected officials” should lead “an objective review of these events, including contributing societal and political factors” that led to the violence that day. On Tuesday, the Senate produced the result of one such review, a joint report of the Homeland Security and Rules Committees that assesses the “security, planning and response failures on January 6.”

The document points to the necessity of a thorough investigation of January 6 to get at questions the two Senate committees were unable to address. Commentators were rightfully quick to point out that among the unanswered questions, of course, is the role of Donald Trump and his White House as well as the Department of Defense that day. For instance, the report says the Department of Justice and the DC National Guard “have conflicting records of when orders and authorizations were given, and no one could explain why DCNG did not deploy until after 5:00 pm.” It also notes the Department of Justice was responsible for security preparations ahead of January 6, “but DOJ did not conduct interagency rehearsals or establish an integrated security plan.” These are fundamental issues that need resolution.

But a close read of the report suggests lines of inquiry regarding social media that require substantial, independent investigation. Key aspects of the report suggest the security response hinged on various agency analyses (or lack thereof) of social media posts ahead of the attack, and point to larger questions about the role of the platforms in propagating the false claims that created the conditions for the insurrection and facilitating the actions of the insurrectionists themselves. For instance, here are three areas of concern prompted by the Senate report:

- Propagating the Big Lie

What is perhaps most important about the Senate report is what it does not include. According to the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent, to pass muster with Republicans, the language in the report notably lacks any reference to “the extent to which Republican lawmakers fed Trump’s lies about the election for many weeks, or the role of this in inciting the rioters, or the degree to which some GOP lawmakers themselves prompted the Jan. 6 event.”

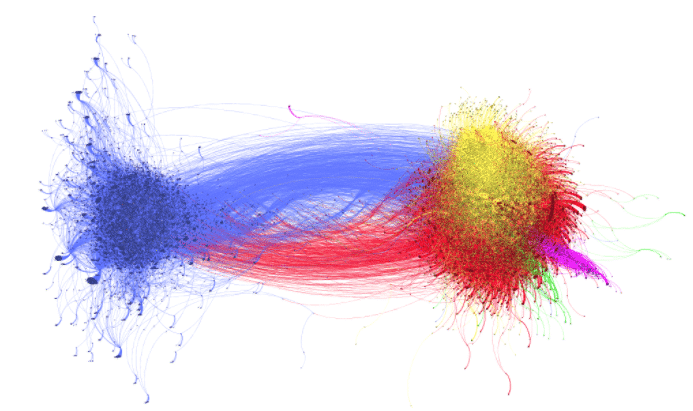

As a result, the document does not get at the substantial questions that revolve around political elites using social media to propagate false claims about the election, and how those claims activated networks the social media platforms permitted to thrive, such as QAnon and white nationalist groups. As University of Washington researcher Kate Starbird has described, the “participatory disinformation” campaign that comprises the Big Lie involves a set of relationships and feedback loops between political elites, media, and the crowd, with social media serving as both connective tissue and as an incentive engine. What can the country learn about the weaknesses of our information ecosystem from better understanding the events of January 6? An unfathomable amount.

Some research and data is available already. The whole of publicly available contents of Parler through to just after the insurrection is readily accessible, for instance. Researchers at Cornell Tech, for their part, have already identified key accounts on Twitter that drove a substantial proportion of false election claims on that platform. Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) produced a report containing false claims about the election on social media from more than a hundred Republican members of Congress, including posts that glorified the events of January 6. And, Facebook promises its collaboration with select academic researchers will produce useful information, which is expected to appear by the early part of 2022. But, the platforms removed a massive amount of material related to January 6 and false election claims in moderation actions. And, there is too little data at the moment on the relationship between social media and traditional media. A thorough and independent investigation would acquire all of the relevant data and create a clearinghouse for journalists, researchers and the public to assess it in a manner that respects privacy and free expression concerns.

- Assessing violent extremism online

A clear set of problems identified in the Senate report revolve around the processes and methods that domestic intelligence agencies and law enforcement entities use to monitor social media for violent extremist threats, how they assess the credibility of threats to find signals in the noise, and the channels and protocols for sharing actionable data in time to act on it. The report concludes that “FBI and DHS acknowledged that the Intelligence Community needs to improve its handling and dissemination of threat information from social media and online message boards.” And indeed, multiple assessments and reports, including from the US Capitol Police, pointed to the potential for violence and highlighted specific threats that were not acted on in advance. The report notes that US Capitol Police analysts “knew about social media posts calling for violence at the Capitol on January 6, including a plot to breach the Capitol, the online sharing of maps of the Capitol Complex’s tunnel systems, and other specific threats of violence.” But this information was not communicated to Capitol Police “leadership, rank-and-file officers, or law enforcement partners.”

Part of the issue is, of course, the sheer volume of social media, and discerning what is worthy of attention. While Facebook and other social media platforms vaunt their efforts at reducing the prevalence of such extremist posts, the volume is still substantial enough that it is exceedingly difficult to identify content that should prompt action. For instance, the Senate report quotes one DHS intelligence official who cautioned that dealing with social media is “‘nuanced’ and that it can be difficult to distinguish between mere rhetoric and overt threats.” The Senate report references a December 30, 2020 DHS assessment on the “diverse domestic violence extremism landscape” indicating that volume is a significant problem: “‘the use of social media to make threats of violence upon which [domestic violent extremists] often do not act’ is a limitation on DHS’s ability to detect and disrupt domestic violent extremist plots.”

A reason detection is so difficult is the ways in which extremists utilize social media, as well as First Amendment limitations intended to prevent the government from encroaching on political activity. On this point, the Senate report quotes Melissa Smislova, Acting Under Secretary of the DHS Office of Intelligence And Analysis:

A lesson learned from the events of January 6th is that distinguishing between those engaged in constitutionally-protected activities from those involved in destructive, violent, and threat-related behavior is a complex challenge. For example, domestic violent extremists may filter or disguise online communications with vague innuendo to protect operational security, avoid violating social media platforms’ terms of service, and appeal to a broader pool of potential recruits. Under the guise of the First Amendment, domestic violent extremists recruit supporters, and incite and engage in violence. Further complicating the challenge, these groups migrate to private or closed social media platforms, and encrypted channels to obfuscate their activity.

A comprehensive investigation might delve into these issues, querying how the platforms identify and flag potential violent threats to government, the efficacy of tools and threat models that agencies and law enforcement use to discern what social media behaviors deserve attention, and how to defend against government or law enforcement excesses that may infringe on free expression.

- Understanding the size and momentum of the insurrectionist movement

A genuine investigation of January 6 should not stop at merely understanding the events of that dark day. A key question it should consider is the nature of the threat going forward. What is the size of the insurrectionist movement? What is the status of false claims related to the election on social platforms in the months since January 6? How effective are content moderation strategies at containing such false claims? How are groups and individuals who were affiliated with the Stop the Steal movement reformulating or reconnecting?

There is ample polling and other data that suggests the insurrectionist movement in the United States may be much larger than previously understood, including from the University of Chicago Project on Security and Threats and the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). Some experts, such as Cynthia Miller-Idriss, the director of the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab at American University, see in January 6 the emergence of a coalition of groups around accelerationist ideologies. The common venue for this coalition -- their virtual watering hole -- is indeed social media.

While Donald Trump may still be exiled from Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, the shadow of his presence remains visible in the networks that continue to propagate his message of the Big Lie -- and the social, cultural, and political effects are still being felt. As the New York Times’s Maggie Astor detailed in a report last month, even though the former President’s “monthslong campaign to delegitimize the 2020 election didn’t overturn the results,” “his unfounded claims gutted his supporters’ trust in the electoral system, laying the foundation for numerous Republican-led bills pushing more restrictive voter rules.”

Indeed, the feedback loop Astor describes is very much alive -- manufacturing and advancing a false reality that may have yet more profoundly dangerous real-world implications. In a stunning letter published last week, one hundred scholars of democracy warned about the “radical changes to core electoral procedures in response to unproven and intentionally destructive allegations of a stolen election,” noting that “these initiatives are transforming several states into political systems that no longer meet the minimum conditions for free and fair elections. Hence, our entire democracy is now at risk.” Researchers, government officials, responsible news media, and other participants in civil society must come together to interrupt the loop, and extinguish the Big Lie. An independent investigation that takes into account the role of social media is necessary to identify potential points of leverage. The longer it takes to set up that investigation the more intractable the problems may become.

Published jointly with Just Security.

Authors