San Diego, Street Smarts and Surveillance

Ellen P. Goodman, Kayvon Paul / Nov 30, 2020What happened in San Diego with its smart streetlights is easily cast as a story of technology creep: LED lights turned into surveillance machines without citizen knowledge. But it is also the opposite story: intrusive data-gathering in plain sight. No subterfuge, just surrender. What started out as energy-saving smart streetlights became a tool to surveil Black Lives Matter protests in the spring of 2020. What was part of the movement to open up urban data for public use also boosted the enclosure of data for private profit. San Diego “woke up” in 2020 to the outrage that police were using clandestine video for law enforcement. But the likelihood that the infrastructure would be used this way was written into San Diego’s contracts with the smart tech vendor from the start. That the public awakening was sudden is only because there was no – and typically is no -- watchdog to surface the concerns before the possible became the unstoppable. This is a story at the intersection of urban infrastructure and policing, of civic open data and data profiteering, of privacy and exposure.

***

The story begins in 2016 when San Diego entered into a $30 million contract with a General Electric subsidiary to build “intelligent sensor nodes” in some 4000 streetlights. The contract provided the company with rich opportunities to collect and mine data, but these were not highlighted. Government officials from the city’s Environmental Services Department hailed the new low-energy LED lighting for its superior illumination and energy efficiency. The city’s project director, Lorie Cozio-Azar, emphasized to the press that the cameras did not capture video (currently). City Council approved the deal without questioning the surveillance capabilities of the technology or management of the data. A close look at the contract would have revealed the likelihood that the streetlights would host video cameras, WiFi, and a wide array of environmental sensors. It would also have shown that the city did not tightly control the data. The vendor – originally GE Current, which sold to Ubicquia – would own all “processed data” derived from the project. City agencies would also have access to the underlying data. It took several years for these facts to became controversial.

Public awareness that the San Diego police were using the smart streetlight data seems to date from a 2018 murder investigation. “We had never seen a video from any of these cameras before,” said Jeffrey Jordon of the San Diego Police Department. “But we realized the camera was exactly where the crime scene was.” More than 200 investigations would ultimately use smart streetlight video. Once it became clear how useful the footage might be for law enforcement, the police and other city offices started to cooperate. “We could have done a better job of communicating with the public that there had been a change in the use of the data. . .One could have argued that we should have thought this through from the beginning,” said city official Erik Caldwell.

The change to which Caldwell refers happened in late 2018 when the San Diego Police Department acquired direct access to the streetlight network. From that point, officers extracted video feeds from the streetlight data as needed and according to their own policies. Civil society began to notice; citizen watchdogs formed a coalition called TrustSD. The “footage was only supposed to be accessed for certain serious crimes and we saw that they were being accessed for very minor crimes like vandalism," said Genevieve Jones-Wright, a community activist. In November of 2019, a candidate for city attorney campaigned on allegations that GE was selling personal data to third parties, comparing GE to Cambridge Analytica in the Facebook data mining scandal. Both GE and the city denied that data had been sold, although the contract permitted the vendor to use and make available data analytics.

On January 28, 2020, the incumbent city attorney, having fought off her challenger, released a report on the city’s use of streetlight data. This report made clear what had been evident since City Council first approved the deal for “advanced technologies [that] will expand the practical uses” of the lighting. The sensors were collecting data “for purposes of … public safety." This was part of the vendor’s “Situational Awareness service” providing “access to media such as photos and video collected from intelligent lighting sensors along public roadways and in parking lots." Four years after inking the deal, the city was reporting that it was getting the services it had contracted for and that City Council had approved, albeit without public awareness or discussion.

Around the same time as the city attorney’s report, an internal city memo revealed that San Diego’s smart streetlight program was suffering from poor oversight, poor training, and significant unanticipated costs. It may be that these oversight problems led to the biggest controversy yet: the city’s use of the smart streetlight footage to surveil incidents connected with the spring’s Black Lives Matter protests. In May and June 2020, the San Diego Police Department accessed smart streetlight data at least 35 times over a five-day period. It now appeared that the police were not only using the smart streetlight data for felony investigations. They were also using the data to investigate misdemeanor vandalism, looting, and destruction of property.

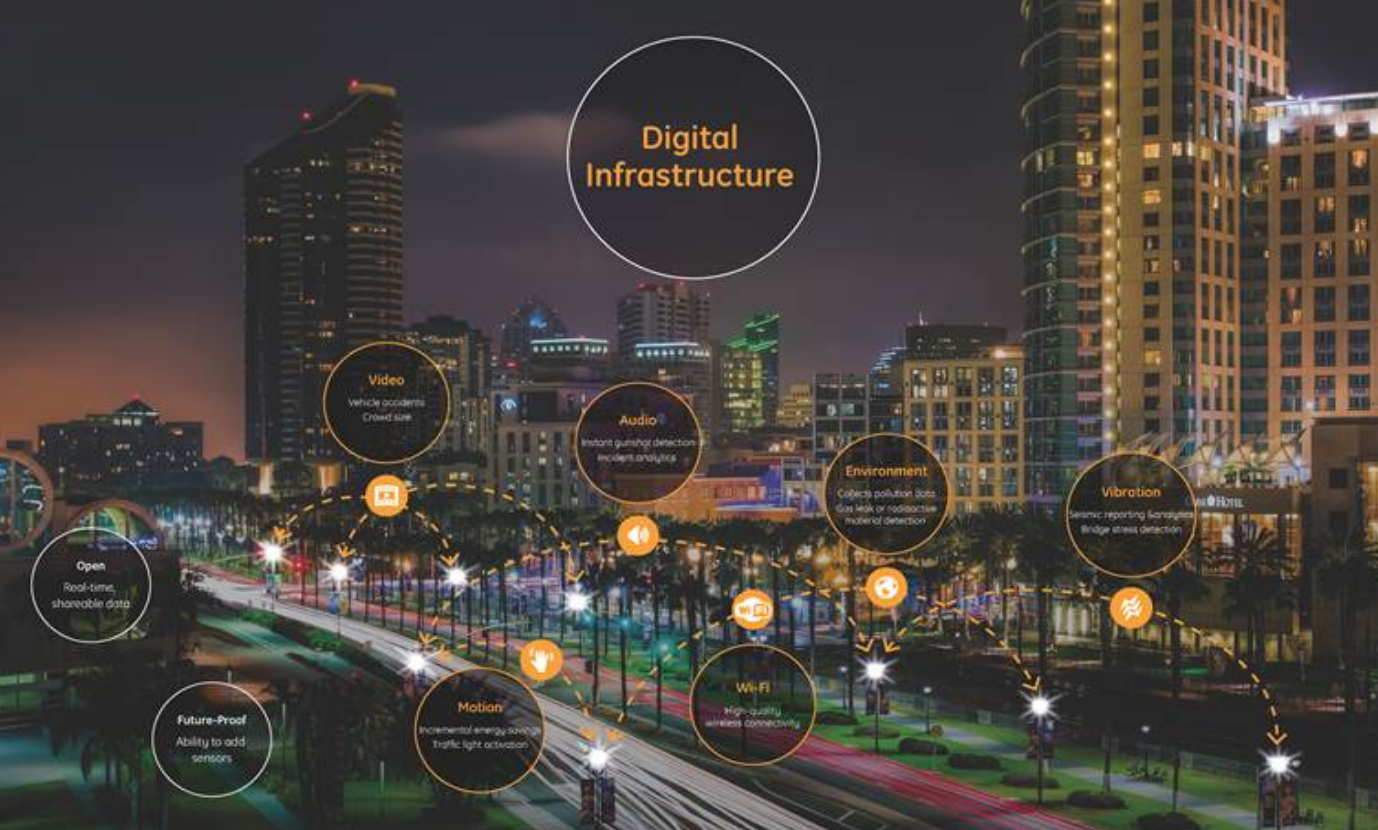

As much as it seemed to shock community members that benign streetlights were part of a police surveillance network, this possibility was always clear. What was missing were the policy and public tools to interrogate these networks. The smart city installation obscured by design the extent of data collection entailed in the partnership between GE and San Diego. Not long after GE inked the deal, it boasted about the ambitions of the modest-appearing LED lights that “are actually data-gathering machines.” Nearly invisible, these intelligent nodes were intentionally “designed to blend in” and “[would] allow San Diego to build the largest municipal internet-of-things network in the world.” San Diego was the first city to pilot GE’s intelligent cities platform that connected sensor nodes to GE’s system of smart city data analytics, called Predix. These sensor nodes clearly included video and audio capture. The below images come from a slide deck the city of San Diego presented to citizens in 2017.

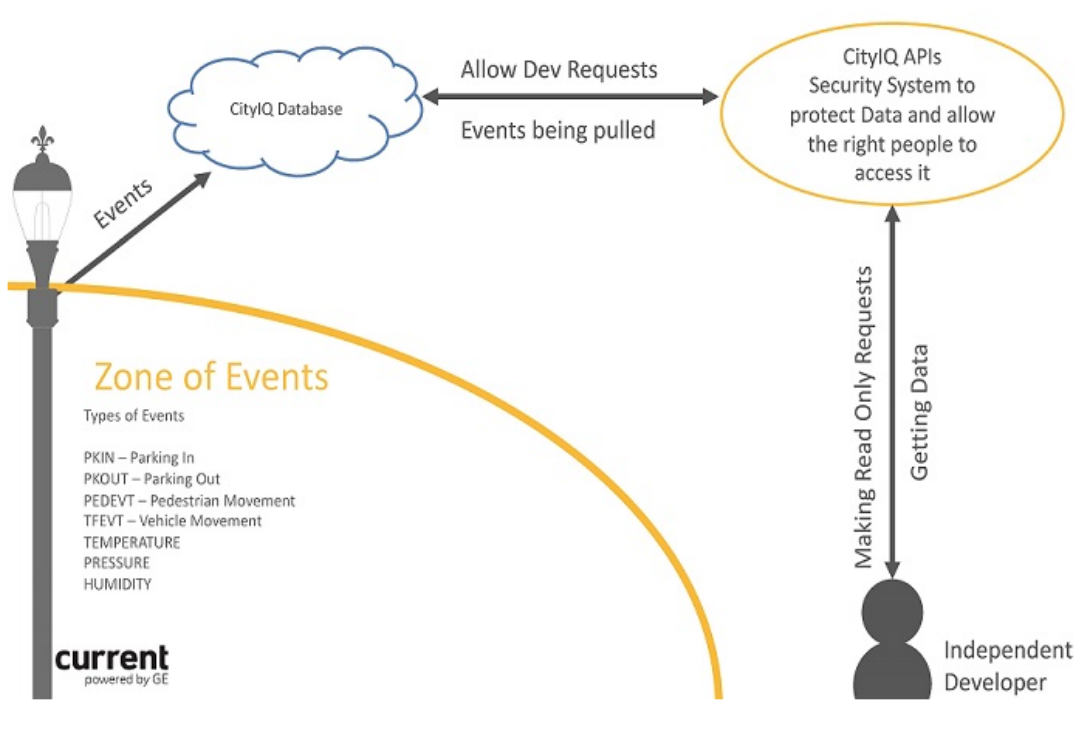

The surveillant possibilities were evident, but not what city officials emphasized – not to City Council and not to the public. Instead, the selling point of the network sensors was that they would push data through an open data portal. From this portal, members of the public would have access to anonymized and aggregate traffic data, environmental performance metrics, and other place-based data. These are what the city depicted in its slide deck as “Events” that are recorded in the CityIQ Database.

The open data movement has long urged cities to make this kind of data available to feed app developers and foster municipal accountability. Monitoring traffic, pedestrian density, and temperature is all surveillance. It is all making the city legible. But what data is made available to whom and how makes all the difference. Without clear governance of data flows at the outset, or a public watchdog to ask the right questions, smart city contracts are bound to surprise the public with surveillant features they don’t want.

San Diego let its contract for the smart streetlights expire in June 2020, but the vendor agreed to keep the cameras on so that the police could still access the footage. The smart streetlight data was so important to the police that the department was reportedly even willing to cover the $7 million in cost to run the sensor network itself for a few years.That didn’t happen. In September 2020, it was reported that San Diego had decided to “deactivate” all sensor services, including cameras, until a new data governance ordinance was in place to regulate them. Mayor Kevin Faulconer expressed frustration that City Council’s failure to provide policy guidance made it politically necessary to pause use of the data. “We’ve seen killers caught, innocent people exonerated, and crimes solved,” the mayor tweeted, urging Council to pass surveillance legislation and approve another tech contract.

While the mayor faulted City Council for impeding the flow of data, apparently that flow actually did not stop. The vendor was calling the shots, not the city. It seems that San Diego could not actually disable the cameras without turning off the lights, and the vendor would not solve this problem until the city had met all its financial commitments. Fights between cities and their vendors over smart city contract performance play out in the street. New York City’s vendor responsible for the LinkNYC WiFi kiosks reportedly owes the city millions of dollars. Kiosks have gone un-installed. In San Diego, it may be the city that is in arrears and the installation is too solid. One of the features of these urban tech deals is a brittleness that leaves the public vulnerable to contract fights, without sufficient redundancy built into the systems.

In the meantime, San Diego’s City Council is acting. It has produced draft legislation modeled after the City of Oakland’s surveillance ordinance but with additional requirements. Most significantly, it would require an annual surveillance report that disclosed how data is shared internally, identify the race of individuals surveilled, and provide notice of authorized and unauthorized system access. On November 10, 2020, the City Council voted unanimously to approve the ordinance and the creation of an advisory board to oversee the uses of technology. Six employee unions (including the city police) have exercised their right to review and propose changes before the final vote. It seems that in San Diego the lesson of the streetlights has been that urban tech contracts require serious review and public engagement before they are signed. To be effective, this really needs to include a mapping of how, to whom, and for what purpose the data will flow.

Authors