Researchers Release Comprehensive Twitter Dataset of False Claims About The 2020 Election

Justin Hendrix / Jun 15, 2022This article is co-published with Just Security.

On Monday, June 13, the House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol hosted the second of its planned series of public hearings, focused on the Big Lie that the election was stolen from former President Donald Trump. The Chairman of the Committee, Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-MS), said in his opening statement on Monday that the Committee’s investigation has established that Trump “betrayed the trust of the American people. He ignored the will of the voters. He lied to his supporters and the country. And he tried to remain in office after the people had voted him out—and the courts upheld the will of the people.”

On the same day the Committee laid out evidence that Trump and his associates knew the election was lost even as they cynically pushed the Big Lie, a group of researchers from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public and the Krebs Stamos Group* published a massive dataset of “misinformation, disinformation, and rumors spreading on Twitter about the 2020 U.S. election.” The dataset chronicles the role of key political elites, influencers and supporters of the President in advancing the Big Lie, exploring how key narratives spread on Twitter.

Published in the Journal of Quantitative Description, the paper accompanying the dataset is titled Repeat Spreaders and Election Delegitimization: A Comprehensive Dataset of Misinformation Tweets from the 2020 U.S. Election. The dataset, which the researchers named ElectionMisinfo2020, “is made up of over 49 million tweets connected to 456 distinct misinformation stories spread about the 2020 U.S. election between September 1, 2020 and December 15, 2020,” and it “focuses on false, misleading, exaggerated, or unsubstantiated claims or narratives related to voting, vote counting, and other election procedures.”

“President Trump and other pro-Trump elites in media and politics set an expectation of voter fraud and then eagerly amplified any and every claim about election issues, often with voter fraud framing,” said one of the lead researchers, Dr. Kate Starbird, an associate professor at the University of Washington and co-founder of the Center for an Informed Public. “But everyday people produced many of those claims.” The new report sheds light on how these claims proliferated from the margins to the nation’s Capitol.

The Nature of False Claims about the 2020 Election

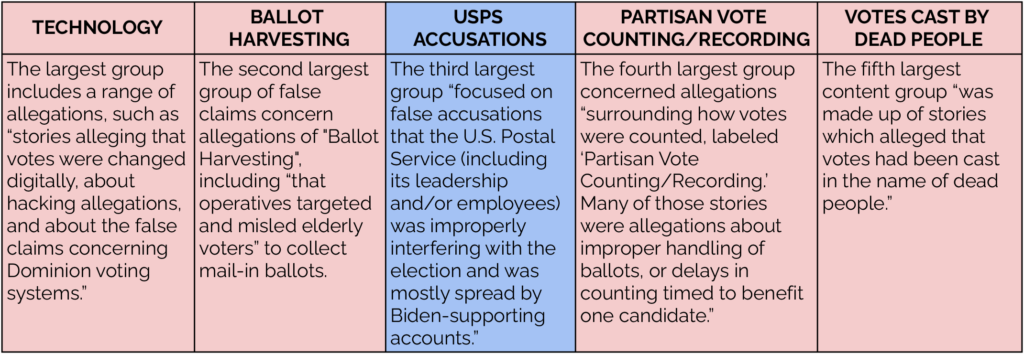

The researchers collected 307 distinct “stories” or narratives, encompassing 44.8 million tweets, that they labeled as ‘sowing doubt’ in the 2020 election.** After a painstaking project to annotate and group the stories, the researchers were able to see patterns in “content groups,” or “collections of stories that have similar narrative or thematic components” representing the broadest categories of stories.

Notably, while “four out of the top five content groups were primarily spread by Trump-supporting accounts,” the researchers conclude, a set of allegations about possible U.S. Postal Service involvement in election fraud was primarily advanced by Biden supporters. But the overall proportion of misinformation was “highly skewed toward pro-Trump accounts” throughout the period.

The largest story in the dataset revolved around Dominion voting systems and claims its software “had systematically changed votes from candidate Trump to candidate Biden.” Spawned from reports of a single “mistake in the process of updating the software on vote tabulation computers” in Antrim County, Michigan, which was quickly corrected, the story was adopted by Donald Trump Jr., and then by President Trump, who tweeted about “dominion” 24 times between Nov. 6 and Dec. 15, 2020. “Dominion,” concludes the researchers, “was a prime example of an isolated incident which was reframed to suit the narrative that election fraud was systematic and widespread.”

Another prominent story is what came to be known as “Sharpiegate,” an example of the set of allegations in the ”partisan vote counting/recording” content group. Sharpiegate started “when voters in several polling locations,” mostly in Arizona, “noted that the Sharpie pens they had been given to vote were bleeding through the ballots—and some began to share concern (and later suspicion) that their votes had not been counted.” While the claims were wrong, Sharpiegate concerns, shared first by social media accounts with limited reach but soon spreading to larger accounts, exploded after Arizona was called for Biden. Later, claims on the account @CodeMonkeyZ, run by prominent QAnon figure Ron Watkins, pushed Sharpiegate further.

Repeat Spreaders

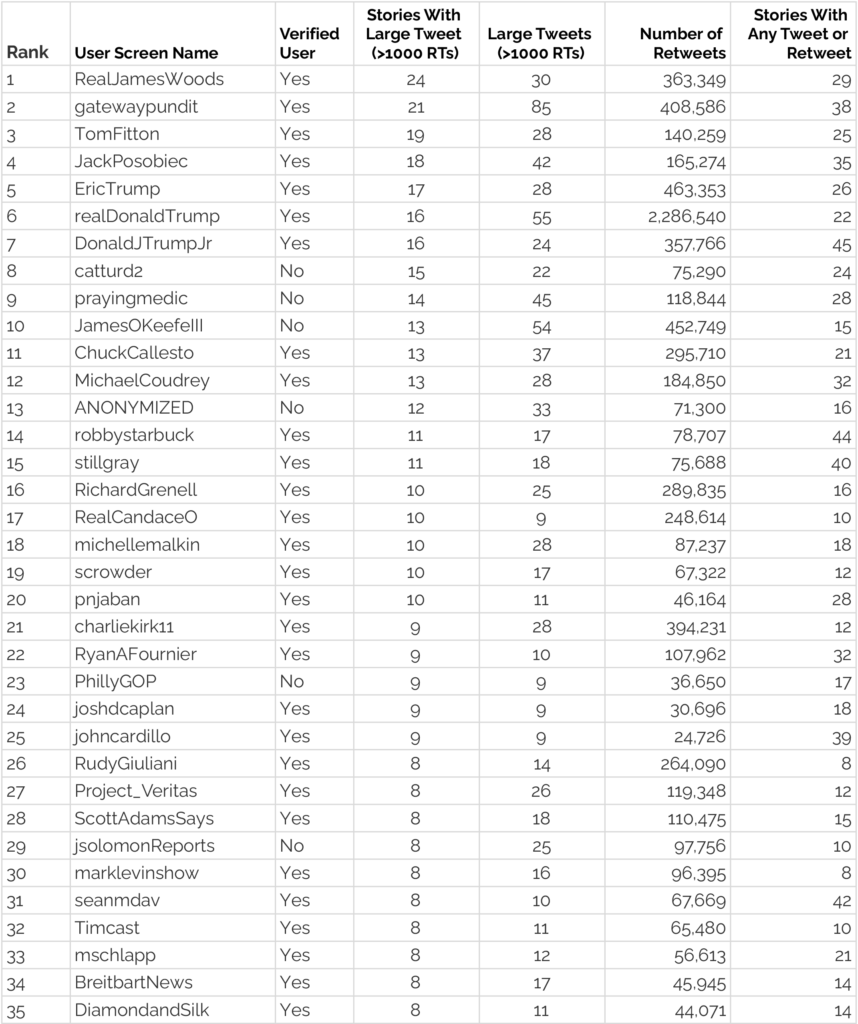

The analysis was also able to “identify high profile accounts who had highly-retweeted tweets in several distinct misinformation stories—specifically among stories that functioned to sow doubt in election procedures or election results.” These "repeat spreaders" had a disproportionate impact on the total misinformation spread across the entire Twitter platform during the 2020 election, as measured by their spread of “multiple, distinct misinformation stories.” The top 35 “repeat spreaders” include far-right media entities and influencers, QAnon personalities, campaign advisors such as Rudy Giuliani, and the former president and his sons.

Possible Interventions

The researchers conclude with observations on potential interventions platforms might consider, including addressing “repeat spreaders.” Since incentives on Twitter are “tied to follower interactions, lesser interventions, such as content labeling, are not likely to have a significant impact on the willingness of these accounts to interact with questionable content.” The researchers suggest that a more “fruitful” approach may be to enforce rules “more stringently” on repeat offenders.

This could include the implementation of “strike systems” presently in use on Twitter and YouTube, which impose escalating penalties on accounts for each rule violation to discourage repeat offenses, or a combination of approaches. So far, however, these strike systems appear not to have been sufficient to reduce the reach of repeat spreaders of misinformation: of the 35 repeat spreaders identified in the table above, “most continue to post on Twitter to a wide audience.” While seven of the accounts were suspended after the election, only two were removed for violations of Twitter’s policy on disputed election claims. (Notably, a number of Republican elites have continued to use Twitter to sow doubt in the 2020 election, with no apparent consequences.) More consistency in application, increased penalties, or improvements in social media companies’ capacities to limit the amplification of misinformation may be necessary to avoid repetition of these patterns in upcoming election cycles.

The Path to the Capitol

While the dataset only includes tweets through Dec.15, 2020 – notably before Trump’s Dec. 19 tweet announcing a “[b]ig protest in D.C. on January 6th” that kicked off a frenzy among his supporters – it does collect stories that relate to political violence. The researchers chronicled “118 unique stories in the broader ElectionMisinfo2020 dataset related to violence or threats of violence, split between the content groups intimidation (38), suppression (21), riots (18), discussions of a potential coup (16), protests (16), and discussions of civil war (9),” and posit that more work is necessary to understand the relationship between misinformation about elections and political violence.

On Capitol Hill, the January 6 Select Committee hearings have already made clear that Donald Trump, who not only generated his own false claims about the election but also embraced, endorsed, and amplified the false claims made by his supporters, played a key role in the incitement of the attack on Congress. “Mr. Chairman,” Select Committee Vice Chairwoman Liz Cheney, R-WY, stated in Monday’s hearing, “hundreds of our countrymen have faced criminal charges, many are serving criminal sentences because they believed what Donald Trump said about the election and they acted on it.”

Researcher Kate Starbird notes that Trump and his loyalists were very effective in creating a participatory mechanism designed to manufacture and reinforce false claims to sow doubt in the outcome of the election.

“One thing we should remember is that President Trump and his campaign were not only repeatedly sharing false claims that the election was or would be rigged,” said Starbird, “but they also encouraged his supporters to share evidence of voting issues — through the ’Army for Trump’ and ‘Defend Your Ballot’ initiatives. The Trump campaign provided the structure for participation in the ‘voter fraud’ disinformation campaign. In other words, they not only encouraged people to participate in supporting Trump, but they gave people a mechanism through which to participate — through sharing claims about voting issues and potential fraud.”

Looking Forward

While the January 6 Select Committee is due to complete its work later this year, the ElectionMisinfo2020 dataset will likely serve as a substantial building block for years of future research on phenomena at the intersection of social media, politics, and democracy.

A key question social media researchers seek to address is how to determine the role false claims and disinformation play in political violence. Starbird says while we all saw “hashtag-warriors come to life on the Capitol grounds and then swarming within the Capitol building,” it can be difficult to discern what sparked violence, or to disambiguate “organic” versus “coordinated” behavior. The Proud Boys who instigated the first confrontation with Capitol Police and used force to breach the building certainly bear substantial responsibility for the violence that day, but what encouragement did they feel knowing they had the crowd at their backs — both on the day and in the online spaces where they planned the attack?

The ElectionMisinfo2020 dataset of tweets, massive as it is, may also eventually be federated with other datasets drawn from other social media platforms during the 2020 election cycle. The complete contents of the social media site Parler were scraped by researchers, for instance, through January 2021, and some academic researchers had substantial access to Facebook to conduct research during the 2020 cycle. “I do think it would be very valuable to put some of the datasets together, but it can be methodologically challenging to combine data streams,” said Starbird. Such combinations could produce new insights.

Certainly, understanding how claims that delegitmize elections spread across platforms is urgent business, both for the Select Committee and for the platforms themselves. As the researchers note, according to one poll, “31% of the U.S. population still believe the ‘big lie’ that the election was stolen from then-President Trump.” And, far right Republican candidates that have spread falsehoods about the 2020 election are advancing in campaigns for pivotal positions of power related to election administration. With another election cycle looming, it is crucial that insights on how to confront the Big Lie inform decisions taken by firms such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube and the recommendations the Select Committee makes to Congress, lest the next mob is too large to resist.

*Alex Stamos, the former Facebook Chief Security Officer who heads the Stanford Internet Observatory, started the Krebs Stamos Group with Christopher Krebs, the former director of the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) who was fired by Trump on November 17, 2020 for asserting that the 2020 election was “the most secure in American history.”

**The paper and data set built on the work of the Election Integrity Partnership (EIP), a collaboration of the University of Washington Center for an Informed Public; the Stanford Internet Observatory; the Atlantic Council’s digital forensics research unit, DFRLab; and Graphika, a firm that tracks disinformation. EIP monitored election misinformation in real time ahead of the 2020 election, identifying and tracking the spread of false claims.

Image: WASHINGTON, DC - NOV. 14, 2020: "Voter Fraud" rally marches to Supreme Court in support of Donald Trump, who refused to concede election. Women for America First, Stop the Steal, Million MAGA March. Bob Korn/Shutterstock

Authors