Researchers detail manipulation of Twitter in 2019 Indian election

Justin Hendrix / Nov 2, 2021After the 2019 elections in India, Twitter released figures vaunting the degree of engagement on its platform in the world's largest democracy. It reported 396 million "conversations" from January 1st to May 23 that year, a figure it said was a 600% increase over the prior election period in 2014. "Prime minister Narendra Modi emerged as the most mentioned political personality throughout the course of elections, while @BJP4India," the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP, "was the most mentioned political party on Twitter," reported the Economic Times.

In a new paper, researchers at MIT and Cornell Tech have revealed one factor driving the volume: an organized network of hundreds of WhatsApp groups coordinating posts and hashtags. "Centrally controlled but voluntary in participation," the groups point to the emerging "blueprint for participatory media manipulation" by political parties in India and elsewhere.

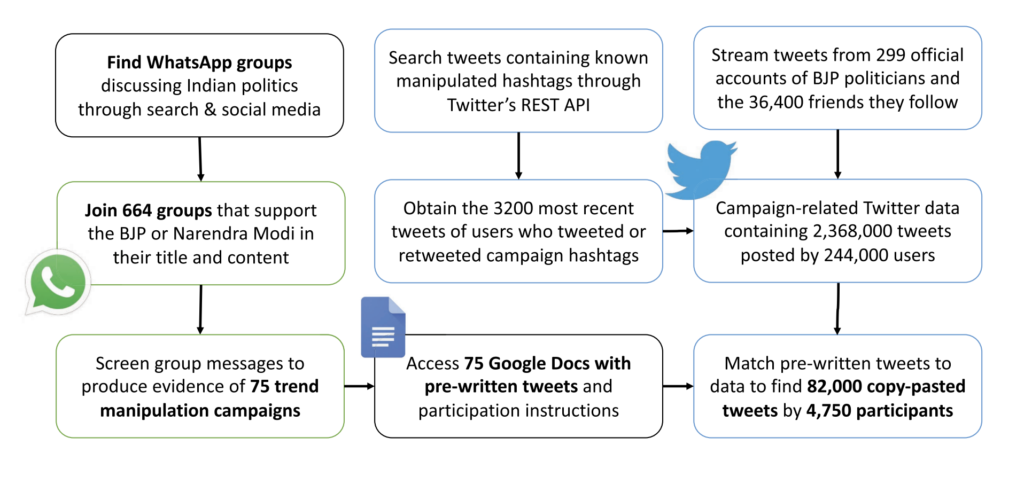

For the study, the researchers joined "more than 600 public WhatsApp groups that support the BJP" to observe how messages propagated and how the groups coordinated. What they found is a "hybrid configuration of technologies and organizational forms that turns online supporters into a manageable political resource" at great scale. Drawing on prior research on astroturfing-- "a genre of social media manipulations where organizations seek to influence debates by creating the impression of a genuine citizen movement"-- the study turned up ways in which this "permanent campaign" resembles and differs from astroturfing.

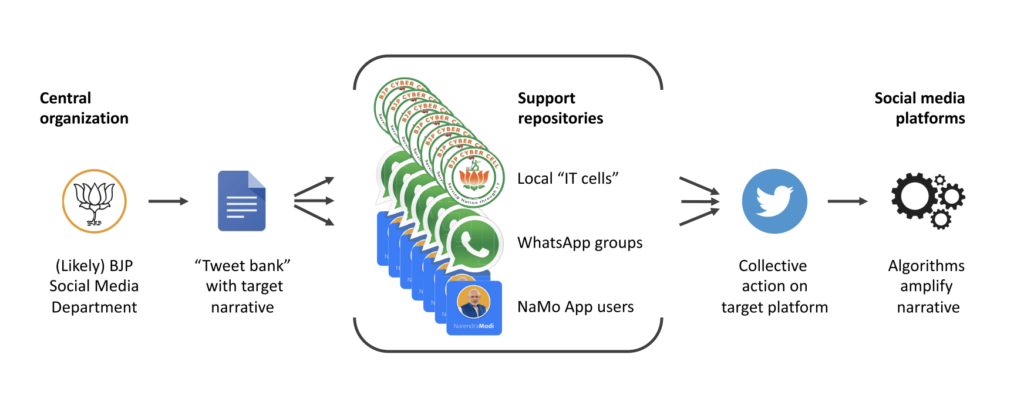

The researchers found that the organizers of the campaign created a variety of "cross platform infrastructures" to accomplish it, including:

- "Support repositories" of WhatsApp groups that collected tens of thousands of supporters into a network. The researchers found that "admins posted messages to different groups within milliseconds, hinting at automation tools and a coordinated organizational effort behind seemingly separate groups."

- The use of "trend alerts" to broadcast messages intended for promotion along with hashtags and links to collections of sample tweets and images stored in Google docs.

- Some interoperability between the tweet banks and the "official Narendra Modi app," which the researchers say "proves the BJP’s involvement in the campaigns and shows the extent to which hybrid manipulation campaigns cross the boundaries of platforms and organizations."

The analysis of the campaigns found a mix of a "more professional core of regular supporters" interacted with more "loosely affiliated supporters" to produce Twitter trends. The approach appeared to work- of the 75 campaigns the study observed, "69 succeeded in reaching India-wide trend status." In turn, media outlets cover the trends- stories subsequently appeared in Quartz India, Financial Express, HuffPost India, The Hindu, and FirstPost.

Considering whether such campaigns "are legitimate, acceptable to the public, and compatible with platform policies," the researchers raise comparisons to an effort by Michael Bloomberg's presidential campaign, which resulted in the suspension of accounts associated with it:

Twitter’s rules forbid “coordinating with or compensating others to engage in artificial engagement or amplification.” But they allow “coordinating with others to express ideas, viewpoints, support, or opposition towards a cause”. With these vague definitions, Twitter attempts to draw a line between coordination for “authentic engagement” and “artificial amplification”. The policy hinges on a notion of a valid cause that justifies coordinated expression. In the campaigns we observed, at least the occasional participants can be considered genuine supporters of a political cause. Their cause could be right-wing, Hindu nationalist, and even in contradiction with pluralistic and democratic principles. But there is little doubt that their support is genuine, which differentiates the campaigns from the astroturfing activities by the Bloomberg presidential campaign or the 50 Cent Army.

So, does this approach more closely resemble "publicity" or "propaganda"? The paper raises a variety of questions that have implications across the world-- including about how such efforts are financed and run in connection with political campaigns and leaders, and the extent to which they contribute to the overall sense of the legitimacy of the public discourse and its relationship to election outcomes. The paper acknowledges concerns over "democratic backsliding" in India, an important context in which to consider this phenomenon, just as it is in other democracies such as the United States.

Note: the author teaches a course in collaboration with one of the authors of this paper, Cornell Tech's Mor Naaman.

Authors