Regulating Misinformation on Twitter is a Problem, But There Are Bigger Ones on the Horizon

José Marichal / Sep 26, 2022José Marichal is a professor of political science at California Lutheran University.

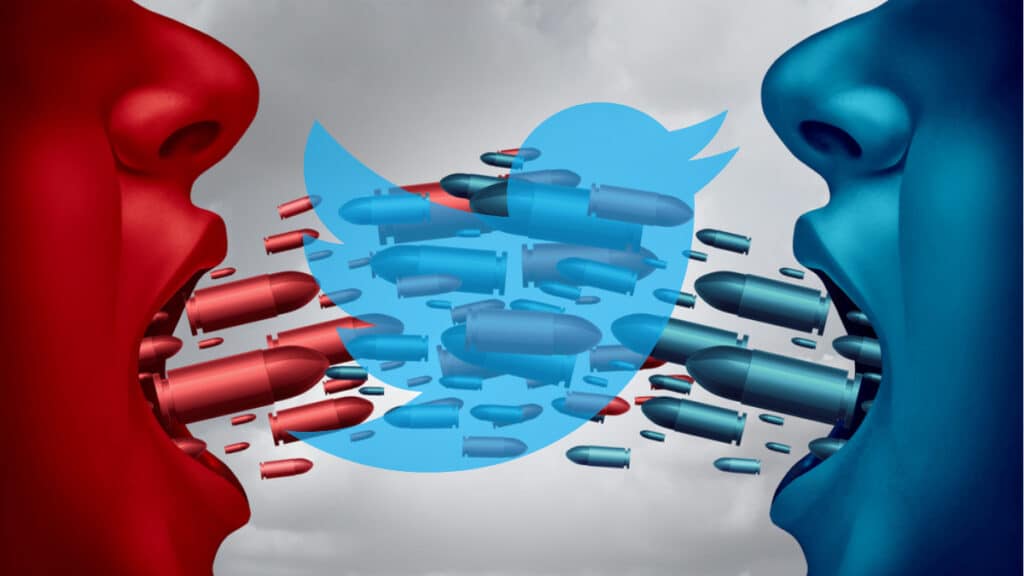

Does Twitter have a censorship problem or a misinformation problem? On September 13th, 2022, a handful of House Republicans demanded that the Biden administration hand over to Congress selected communication between the administration and tech companies. The members of Congress accuse the administration of coordinating with Facebook and Twitter to censor stories and Tweets regarding COVID-19 under the guise of preventing misinformation. While preventing misinformation is a critical issue, it’s not Twitter’s only problem. Equally important is the question of how we can better argue with one another without creating more hatred and antagonism, or as political philosopher Morton Schoolman put it, how can Twitter “eliminate violence towards difference” while at the same time standing for democratic principles?

Over the last two years, Twitter has taken steps to reduce the amount of misinformation users see. In 2021, the company claims it adjusted its algorithm to reduce exposure to Tweets by users whose posts reflect “behaviors that distort and detract from the public conversation.” While this “addition by subtraction” approach may have the effect of creating more polite, or even more accurate, discourse (along with keeping users interested in the site), its effect on democratic health may be as bad as its benefits. While eliminating anti-democratic or simply false posts are an important tool for maintaining a healthy public, the deeper problem with Twitter lies is the way users argue politics with one another.

We Twitter users are generally not nice to each other when we disagree. We are often not generous in presenting the opposing side’s views, or in presenting our own views to those whom we’ve identified as bad-faith actors. We presume nefarious motives about our opponents. This leads many to argue that the problem with social media is “too much arguing.” But agonistic political theorists like Chantal Mouffe maintain that arguing is not only good for politics, it’s what defines it. Argument highlights the contest between “reciprocity [with our in-group] and hostility [towards our out-group]” that creates politics. Without this contestation, there is no politics. The end of contestation means the end of politics. On issues where there is no grounds for agreement, our only non-violent/non-coercive option in a democratic society is to “keep arguing.”

But if argument is essential for politics, does that extend to invidious “trolling” or bad-faith efforts to demean opponents? Another agonist political theorist, William Connolly, suggests that a lack of generosity and distrust towards fellow citizens (not institutions) breeds the ressentiment or disengagement from the political community that serves as the hallmark to democratic backsliding. Indeed, the more platforms become toxic, the more they censor themselves. In unpublished research I am working on with my colleagues Don Waisanen and Carrie Anne Platt, we find that the vast majority of Facebook users we surveyed about political discussion employ more avoidance and censoring strategies online when compared to their off-line behavior.

In other work, my colleague Richard Neve and I found that many Twitter conversation threads had practically no alternative perspectives offered. We studied the top 75 most retweeted users on a given day and found comment threads largely devoid of counter-arguments. Eliminating counterarguments, or even misinformation, might make for more engagement on Twitter, but it does not help users engage in productive arguments. Former Twitter boss Jack Dorsey admitted the limited nature of the company's approach in a series of Tweets in 2018:

We aren’t proud of how people have taken advantage of our service, or our inability to address it fast enough… While working to fix it, we‘ve been accused of apathy, censorship, political bias, and optimizing for our business and share price instead of the concerns of society. This is not who we are, or who we ever want to be… We’ve focused most of our efforts on removing content against our terms, instead of building a systemic framework to help encourage more healthy debate, conversations, and critical thinking. This is the approach we now need.

Over the past four years, however, Twitter has kept its focus on misinformation, understandably because of the substantial challenge of electoral and COVID-19 misinformation. But as Dorsey recognized, any effort to increase the overall health of political discourse on Twitter will need sustained critical reflection, development and implementation. This task is not technical in nature. The value of political engagement cannot easily be judged without taking into consideration substantive considerations concerning meaningful speech.

Agonism gives us a different starting point for addressing Dorsey’s concerns. A key distinction between agonism and antagonism is the latter’s commitment to a “political association” with the other. An antagonistic discourse is one in which one sees opponents as an existential threat rather than as a competitor.

What would an agonistic, “good arguing” Twitter look like? How could we add to, rather than subtract, from the plurality of voices on Twitter? Rather than have a policy of subtraction, I propose Twitter use its algorithms to identify antagonistic threads and populate them with “orthogonal perspectives and narratives” that force users to draw out their own value positions and confront them with generously presented counter-arguments. Even if these “orthogonal” stories, data points or arguments were largely ignored, it would remind users that there are reasonable and plausible counter-narratives in the public discourse.

This “eat your broccoli” approach is not a cure-all solution. This is a uniquely fragile point in time for liberal democracy. The authoritarian impulse in many countries to re-establish a sense of hierarchy and order undermined by globalization and cultural and demographic change often plays out on social media platforms. Calls to redress the injustices of racism, colonialism, and sexism and other axes of oppression are often met with threatening and dehumanizing language. There is a persuasive case to be made that Twitter and other platforms should simply eliminate discourses that reinforce systems of oppression.

There is indeed value in deplatforming content that promotes violence or undemocratic views. But the job of repairing a public sphere can’t simply be left at removing noxious content. Even with the mixed record of success with deplatforming, the unwillingness of Twitter users to meaningfully engage with difference remains. Most people on Twitter do not want agonistic engagement. They prefer to have their worldviews amplified. Or they come to platforms like Twitter for the thrill of abstract, “drive by” conflict. On platforms like Twitter, argument is disembodied from its subject. There is no ability to find the commonalities that would undergird a sense of “political association.” Hence, disagreement is an ambient, disembodied provocation. It is a hostile challenge to one’s sense of emotional and sometimes physical safety.

Re-embodied in place, people disagree on all sorts of things and get on with the work of living collectively. Those who disagree on student loan forgiveness might share a love for the New York Knicks or a passion for needlepoint. But these commonalities would only organically emerge from being in community. That is something that Twitter cannot do.

Authors