Recommendations to End Virtual Stop and Frisk Policing on Social Media

Desmond Patton, Eno Darkwa, Kelly Anguiano / Apr 13, 2021Advocates have long called for the end of racist and punitive justice systems, exemplified by the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) “Stop and Frisk” protocols. Stop and Frisk was proven to have negative effects on Black and Latinx youth’s mental and physical health, from the anxiety inducing, aggressive stops to the time spent physically detained. And, it was ultimately deemed illegal by the courts. But what is less understood by the public is that while Stop and Frisk was discontinued, a virtual version of the practice has emerged as police departments invest heavily in social media surveillance.

This virtual Stop and Frisk policing includes the active creation of online accounts and profiles using faux identities as well as buying data and analysis tools from third parties. The NYPD, for instance, argues that by being accepted as “friends” or “followers,” they bypass the privacy laws which stand to protect the information shared online through social media sites. This draws attention to the imperative demand for legislation which regulates social media tech companies and would also include protections against racially disparate treatment of Black, Indigenous, and communities of color (BIPOC) by law enforcement online.

Due to the perpetually changing nature of the online world, the current laws that cover protections to citizen’s privacy and bodies do not always cover the entirety of personhood online, thus allowing for novel forms of surveillance. To promote inclusivity and reduce racial bias, we recommend policies centered on Restorative Justice principles of community involvement- specifically through social media post analysis, to add layers of interpretation prior to law enforcement surveillance and offline involvement. Restorative Justice requires the shift from the punishment of those violating the law, to centering any community members who have a stake in the specific offense and to collectively identify and address harms, needs, and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible. It is a reframing of who justice should serve, as we believe the addition of those community stakeholders, social justice advocates, youth educators, etc would bring necessary background. Ever emerging technologies necessitate a wide range of experts, social groups, cultures, races, and ethnicities in Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems development, and in this case, social media surveillance.

Background

The SAFElab at Columbia University, which consists of social workers, community members and data scientists, examines ethical technologies and how algorithms, machine learning, and digital surveillance impact Black and Latinx communities. Of particular interest is the role of social media as a digital neighborhood, which has become a community context and integral source of news and communication for youth. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, along with countless other social media platforms, are easily accessible on any device connected to the Internet, and their ability to connect people to the world makes them appealing. Social media usage is prolific amongst teens- a 2018 Pew survey found 95% have access to a smartphone, leading to a good proportion of communications being held online in this age group.

However, the interactions and usage of social media platforms can be performative in that some content posted on these platforms may be inconsistent with real-life presentation. Our research suggests that while computational tools offer new ways of understanding the links between social media communication and gun violence, there are real concerns about the potential for misinterpreting images on social media in the absence of sufficient context. The varied meaning, that of the poster vs that interpreted by law enforcement, of these posts is the critical sticking point, especially in cases where law enforcement agencies rely on them as evidence for investigative purposes.

This widespread digital policing has serious implications for Black and Brown youth’s lives in terms of the carceral system, as communities of color are socially construed/presented to be problematic sites. High density populations of Black and Brown citizens are espoused to have higher rates of crime, which necessitates increased policing, though as previously referenced the rates of crime between races does not differ. Law enforcement creates this technological gaze, that hyperfixates on the socially created problematic sites, morphing the goal from proactive policing to proactive punishment, entrapping innocent individuals. In light of this, the procedures that law enforcement follow do little to protect or police in a way that centers rehabilitation and growth. Evidence has shown that gang-associated youth commonly use social media to challenge rivals, but most of these confrontations are not escalating to offline violence and, in some instances, deterring it. The digitalization of policing has provided a new space where similar offline issues persist and are exacerbated within marginalized populations.

When discussing law enforcement’s role in social media monitoring, a 2018 report by the Brennan Center for Justice shows then New York City Chief of Detectives, Dermot Shea, saying that public social media platforms are like public places and hence are patrolled by the NYPD. However, NYPD’s previous failures to patrol equitably, i.e. Stop and Frisk,' serve as proof of the possibile racial disparities through online surveillance. Such ‘patrols’ of activities (including but not limited to liking/commenting on a post) can land an individual on the NYPD gang database. This database disproportionately patrols and targets communitinities of color: with only 1.1% of the people on the gang database are White, with 66% Black and 31.7% Latinx, with children as young as 13 years old being added. The NYPD does not communicate placement on this gang database, yet being on this database can have negative consequences such as a decrease in the likelihood of release on bail, long sentences, and possible interactions with Immigration and Customs Enforcements (ICE) when the individual is an immigrant.

The most alarming issue however, is the lack of transparency as to how the NYPD determines who lands on this database. Even when barred from direct monitoring, law enforcement agencies use data collected from social media platforms either directly found or through private organizations like Geofeedia or Snaptrends for investigations without these steps taken. The platforms often use provocative pictures of women found online to add individuals as friends or followers, then tracking users’ locations across social media sites, regardless of whether they geo-tag their posts publicly or not. This problem is not peculiar to the NYPD, as police departments, cities, and counties across the nation spend huge sums of money on social media monitoring tools. These disproportionate statistics are found across the U.S. and showcase the racialized undertones that this subversive form of policing has taken. The shift to Restorative Justice grounds our ask for community analysis as a foundation of law enforcement’s interactions with youth of color around social media postings.

Social workers often operate from a space of translating dualities, leading to the development of a social work-based computational approach to this sensitive research, relying onanalysis as distanced as possible from personal bias. This practice has created a system that mostly operates as a trap for Black and Brown communities who perform illegal activities, to no higher degree than White communities, but are policed at much higher rates through every level of the criminal justice system- see QANON vs BLM or the lack of Proud Boy members on NYPD’s gang database. A review completed in January 2021 of law enforcement’s response to more than 13,000 protests showed police were three times as likely to use force against leftwing vs right wing protestors.

Inequities in police perspective of danger leads to the need for communities to monitor posts and de-escalate situations when necessary. This can be achieved through restorative justice community based analysis of posts conducted by community-based experts (these are individuals who share the same cultural background and understand the colloquial language of these youths) with the help of social work based computational approaches. The purpose of this analysis is to determine the underlying meaning of a post and when appropriate discuss with stakeholders and prevent the actualization of violence in real life. However, the current monitoring by law enforcement agencies specifically targets and discriminates against people of color, especially youth.

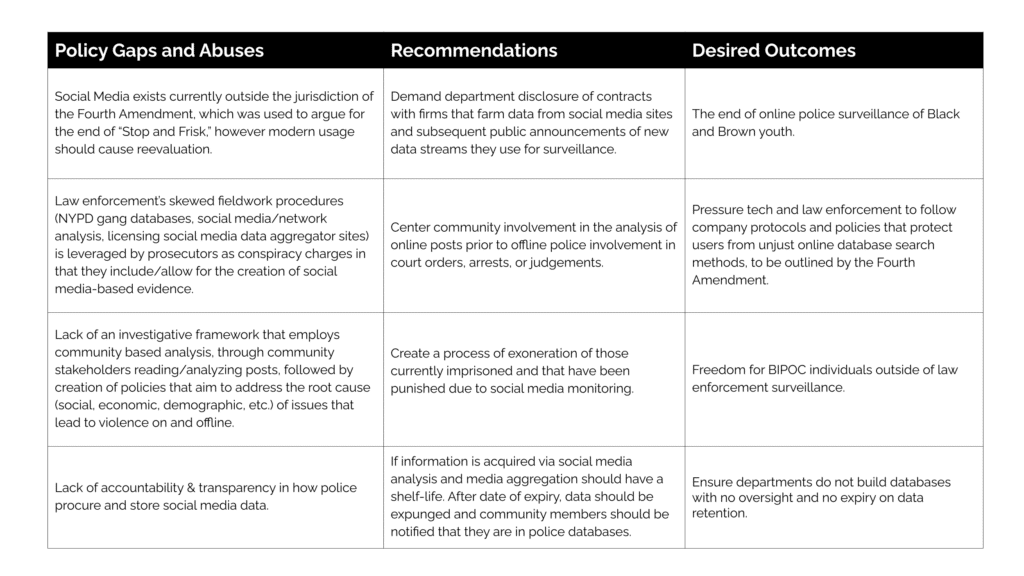

Policy Gaps & Abuses of Power

The internet brought with it a “Wild West'' realm where infringements upon the Fourth Amendment are sanctioned and sought after methods of law enforcement policing. We need social media monitoring policy to be conditional on more than an officer’s “reasonable suspicion” that an individual is engaged in criminal conduct. With data available through examination of pre and post Stop and Frisk' policing, which was found unconstitutional as it infringed on Fourth Amendment Rights, we propose similar restrictions be enforced. While some States require that people identify themselves at the request of police, the Supreme Court has ensured that those laws require a predicate of reasonable suspicion.

Even with regulations independently created by large tech companies, law enforcement actively works to bypass tech organization regulations, even with the regulations specifically cutting access to law enforcement. After the creation of policy by tech organizations that expelled law enforcement from direct monitoring of social media sites, 500 U.S. law enforcement agencies began to license other private companies, Geofeedia, Amazon Ring, and Snaptrends, who have access to back-end developer tools that surveil social media sites. In addition to clear attempts to circumnavigate anti-surveillance regulations, non-profit Working Narratives of North Carolina revealed that “one of Geofeedia’s goals is to bypass the privacy options offered to users on social media sites.”

The current political staging doesn’t require that teens be aware of a specific plan or crime in order to be found guilty of conspiracy. Using California Law as example, Chris Lawson, a San Diego prosecutor, listed out the three necessary components to be able to bring a conspiracy charge against gang members: 1) knowledge of a gang’s criminality, 2) active participation in the gang, and 3) intent to further the gang’s overall goals. Prosecutors and officers can, and do, glean evidence for all of this off social media through the methods previously listed. By adding perspective targets through social media under pseudonyms, law enforcement is circumnavigating that predicate, thus allowing them to identify and surveil an individual without stopping or even talking to them. Our future proposals must ensure that the old regulations guarding personal privacy survives new technology.

Policy Alternatives & Recommendations

Given that social media and other technological advancements seem to be uncharted territory for many policy makers, it is imperative to take steps to ensure that these new technological advancements do not create new avenues or perpetuate old patterns of stereotyping and discriminating against people of color. We are seeing in-person discrimination transform alongside technology, to target and apply outstanding pressure on Black and Brown youth. That shift necessitates an emphasis on prevention in place of stereotyping and/or discriminating. A single arrest and conviction can come with many barriers, not limited to:

- Losing the right to vote

- Difficulty finding and maintaining a job

- Losing access to affordable housing

- Unlawful detainment

With this in mind, we must be future-oriented and ensure protection and prevention without discriminating against youth of color. We can trace the history of protective laws to 1967, where the Supreme Court ruled in Katz v. United States, to expand the Fourth Amendment protection against “unreasonable searches and seizures” to cover electronic wiretaps. This decision to expand came at the necessity to reimagine in the modern age- what would fall under someone’s “persons, houses, paper, and effects” as defined in the Constitution, adding the clause of “what [a person] seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public.” In the spirit of forward progress we recommend the following:

1. End non-community analyzed i.e. solely police analyzed, surveillance of Black and Brown communities online

- This is our largest ask, as well as the most important. We must end the proactive surveillance that does little to stop crime, and instead criminalizes Black youth.

- Transparency of the procedures of law enforcement placing individuals on the databases. Making the information public of placement on the database as well.

- We don’t know about how social media surveillance is used to build the clearly disproportionate databases that have concrete impacts on youth's justice involvement/criminal outcomes.

- Implement a system of community involvement to verify and interpret information being collected by law enforcement, all in accordance with the Fourth Amendment.

- A community composed group, potentially housed in a research lab or non-profit, operating to interpret posts/posters that may be “interesting” to law enforcement. - This will work as the first line of defense in correcting data and posts from becoming misinterpreted or being left unheard. The primary goal of policing should not be centered on arrest and conviction, but rather on understanding, rehabilitation, and growth.

2. Enforce tech company protocols to protect users from unjust search methods by law enforcement or private organization

- Stop developers from using or selling data obtained on their platforms to provide tools that are used for surveillance by law enforcement or other parties.

- “We prohibit developers using the Public APIs and Gnip data products from allowing law enforcement — or any other entity — to use Twitter data for surveillance purposes. Period.” (Twitter, 2016)

- “We are adding language to our Facebook and Instagram platform policies to more clearly explain that developers cannot ‘use data obtained from us to provide tools that are used for surveillance.’ Our goal is to make our policy explicit.” (Facebook, 2017)

- End the ability for police to circumnavigate privacy protocols by adding individuals under surveillance via undercover accounts as a form of entrapment and via contracts with private monitoring services (Geofreedia, Snaptrends, etc.).

- The FBI and police departments must refrain from biased searching of social media posts and from creating databases as a method of modern surveillance.

- End usage of non-official social media accounts for investigations14, with or without written permission from those investigated.

- Transparency around records, history, and racial biases concerning conspiracy charges.

- If information is acquired via social media analysis and media aggregation should have a shelf-life. After date of expiry, data should be expunged and community members should be notified that they are in police databases.

- End conspiracy charges that are formed based on information gleaned from social media surveillance.

3. Exoneration of those who have been punished due to social media monitoring

- Transparency in how law enforcement has gathered and used data from social media platforms in prior convictions, as well as establishing a system/pathway for exoneration of those previously or currently serving time.

- Removal/wipe of online history of law enforcement interaction that does not lead to conviction.

- In her book “Digital Punishment,” Sarah Esther Lageson shares the story of Shana, who had her mugshot pop up every time she Googled her name. Shana is terrified in the photo that was taken at her first and only arrest in Florida after a fight broke out in a nightclub. The arrest never led to any criminal charges, and Shana went home several hours later. Within weeks, her mugshot was posted to dozens of websites, with her full name and address underneath the photo. She became ashamed of her identity all the while jobs and networking were being hindered causing her livelihood to be affected tremendously. Even attempts to control the "search engine optimization" (SEO) by adding positive personal information to the internet was not completely successful in getting rid of the negative mugshots, as her mugshot still showed as one of the top results.

Conclusion

The policies suggested in this memo outline regulations to curb social media monitoring done by judicial systems. We must begin by de-centering the power that is held by law enforcement and tech organizations by bringing in the community as a first line of evaluation for anything online that is being used as evidence. Coinciding with the cross referential analysis, new restrictions must be put in place on both law enforcement as well as the organizations that place both transparency on past actions as well as restrictions on current and future tactics.

Authors