Politicians Move to Limit Predictive Policing After Years of Controversial Failures

Grace Thomas / Oct 15, 2024

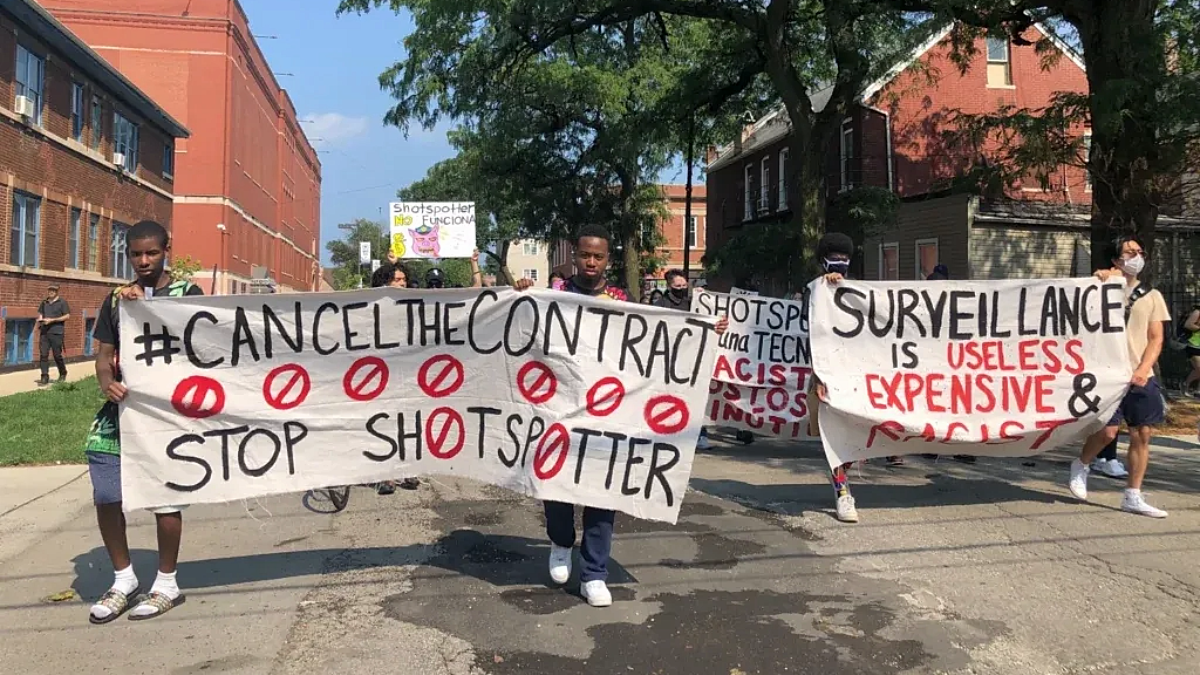

Chicago protestors in July, 2021. Mauricio Peña/Block Club Chicago

In November 2009, Laurie Robinson, then Assistant Attorney General for the Justice Department’s Office of Justice Programs, gave remarks at the first Predictive Policing Symposium in Los Angeles, California, an event hosted by the National Institute of Justice. According to a summary of the event, Robinson noted the participants were gathered to talk “about nothing less than the future of policing in America.” She suggested a number of items for the agenda, including definitional questions. Then she raised a more fundamental concern:

But what about privacy and civil liberties issues — how do we ensure that we’re not overstepping? The very phrase, “predictive policing,” raises questions in many people’s minds. How do we assure the public that our goal is to be less intrusive, not more? I’ve mentioned this symposium to several friends back in Washington, by the way, and gotten pretty wary looks — and a couple of allusions to that old Tom Cruise movie, “Minority Report.”

Fifteen years later, fundamental ethical questions about the use of tools such as data analytics, machine learning and artificial intelligence in the conduct of law enforcement remain unresolved. While "Minority Report" was fiction, what has changed in the intervening years is the accumulation of reasons for concern in the real world. Law enforcement agencies have invested extensive public resources into acquiring new sensors, vast quantities of data, and state-of-the-art software, but mounting evidence suggests that these technologies may be reinforcing the very biases they sought to overcome. Now, politicians are finally paying attention and starting to demand reform.

Across the US, failures mount

Consider three points of evidence from three American cities:

1. Los Angeles, California

In the city that hosted that first predictive policing symposium in 2009, there were high hopes for systems such as PredPol and for Operation LASER, deployed in 2011. The LASER system used software developed by military contractor Palantir to create a “chronic offender score” of citizens based on criminal history, social media, and license plates, and deploy police resources accordingly. It was paid for primarily with funds from the federal government, through the Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Assistance.

But as Brennan Center for Justice researcher Tim Lau noted in 2020, Operation LASER was shut down in 2019 after the Los Angeles Police Department inspector general raised various questions about the program, concluding that it had “difficulty…isolating the impact” of the software, as well as that of PredPol. Documents released by the activist organization Stop LAPD Spying “validated existing patterns of policing and reinforced decisions to patrol certain people and neighborhoods over others, leading to the over-policing of Black and brown communities in the metropole,” according to The Guardian.

2. Chicago, Illinois

Chicago’s foray into predictive policing began in 2012, with the creation of a “Strategic Subjects List,” known as a “heat list,” of people who are most likely to commit a crime or be a victim of one. Each person was given a number from 0 to 500+ based on historical factors, such as if they had been previously convicted. The list eventually grew to over 400,000 people–disproportionately including 56% of Black men in the city. The program was discontinued in 2019 after the Chicago Police Department Office of the Inspector General raised concerns about its efficacy.

Similarly, in mid-February of this year, Chicago allowed its contract with gunfire detection and predictive policing system ShotSpotter to expire. PhD candidates and a national activist group spearheaded this move, collecting research and raising public awareness about how the technology is unjust. Chicago Mayor Johnson, who outlined plans to end the contract in his 2023 campaign, echoed these sentiments, saying in a press release that “Moving forward, the City of Chicago will deploy its resources on the most effective strategies and tactics proven to accelerate the current downward trend in violent crime.”

3. Plainfield, New Jersey

In 2023, an analysis by the nonprofit newsroom The Markup added to “the debate over the efficacy of crime prediction software.” The Markup set out to assess the performance of predictive policing software Geolitica, which operated under the name PredPol until a 2021 rebrand. The analysis considered over 23,000 predictions in 2018,” finding that ”the success rate was less than half a percent. Fewer than 100 of the predictions lined up with a crime in the predicted category, that was also later reported to police.”

The Plainfield Police Captain told The Markup that “the money paid for Geolitica’s software could have been better spent elsewhere.” Later in 2023, Geolitica reportedly sold part of its operations to SoundThinking, the firm that sells (and was previously known as) Shotspotter.

Calls for reform mount in 2024

Given such failures, from the local levels of government to the halls of Congress, political leaders are pushing for reform, often answering the call of advocates. In addition to the advocates referenced above, the ACLU has been vocal about predictive policing concerns as early as 2016. Organizations such as the NAACP, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the Brennan Center for Justice call for various reforms to contain the use of predictive policing. Recommendations range from increasing community involvement in technology deployment, implementing stringent regulatory oversight, and conducting regular bias audits of policing systems, to outright bans on the practice.

There are signs such concerns are being heard on Capitol Hill. On January 24 of this year, seven members of the House and Senate jointly wrote a letter to the Department of Justice calling for an end to the department’s funding of predictive policing projects “until the DOJ can ensure that grant recipients will not use such systems in ways that have a discriminatory impact” and an audit of all grants issued to date. The letter highlighted that evidence suggests the use of predictive technologies may further the unequal treatment of minority communities by law enforcement.

Highlighting similar concerns, Rep. Mark Takano (D-CA) has introduced legislation for the past three congresses, most recently in February, that addresses transparency and testing of forensic algorithms used within the criminal justice system. He has been joined in his effort twice by Rep. Dwight Evans (D-PA) but has not been able to pass the bill.

This March, the White House Office of Management and Budget issued a landmark policy outlining how federal agencies should govern the use of AI. The policy expanded reporting requirements for use of AI “presumed to be rights-impacting,” including a range of predictive policing applications. Agencies must now conduct independent testing of such systems under realistic conditions and conduct a cost-benefit analysis, along with an impact assessment to determine suitability for use. Public feedback is now required to shape decisions surrounding predictive policing, and vendors looking to contract with federal agencies must comply with performance and transparency requirements. Such requirements should mitigate risks of training data bias and ensure companies obtain consent to use data. However, this policy does not touch state and local law enforcement, where the vast majority of policing happens.

Looking abroad

Around the world, predictive policing and surveillance technologies are actively being deployed. According to the 2022 AI & Big Data Global Surveillance Index, at least 97 out of 179 surveyed countries are actively using AI and big data for public surveillance, and 69 of these countries are using AI for “smart policing.” Reported uses varied; for example, South Africa is in the early stages of exploring AI in policing, while “at least 14 police forces in the UK are also known to have used or considered predictive policing technologies” as of 2021.

As in the UK, where there is experience with these systems, there is also resistance. In June of this year, a coalition of 17 civil society groups in the UK called for a ban on biometric surveillance and predictive policing as they magnify inequality and target marginalized groups. The letter says the “systems exacerbate structural imbalances of power.” The coalition called for the government to produce a new legislative framework to provide public transparency and ensure “there is meaningful human involvement in and review of automated decisions,” among other obligations.

In Europe, researchers and civil society groups have raised similar concerns about the efficacy of predictive policing systems, such as in France, Germany, and the Netherlands. In response to such concerns, the European Union agreed last year on a partial ban on systems that make predictions based on an individual’s characteristics or personality traits in the landmark AI Act. The ban does not ban geographic crime prediction systems that many police forces across Europe use, despite mounting evidence of the discrimination baked into such systems. It also includes a “national security” exemption, preventing the entire act from impacting national security contexts. There are some concerns that these loopholes still make space for systemic discrimination.

Conclusion

At that first predictive policing symposium in Los Angeles in 2009, Assistant Attorney General Robinson asked, “How do we convince the public that we’re operating in good faith?” After years of public spending on technologies with questionable or negative efficacy, wrongful arrests, and the exposure of biases in systems that were intended to prevent them, the public and those who represent them are right to remain skeptical. Yet law enforcement investments in technology are only anticipated to grow over the next decade. 2025 and the years beyond will determine whether political leaders and legislators can ensure the types of reforms necessary to crack down on the harms of this generation of predictive policing technologies. One thing is clear: predictive policing has over-promised and under-delivered, and communities of color have carried the brunt of its failures.

Authors