Platforms are Abandoning U.S. Democracy

Daniel Kreiss, Bridget Barrett / Jun 29, 2023Bridget Barrett and Daniel Kreiss are researchers at the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

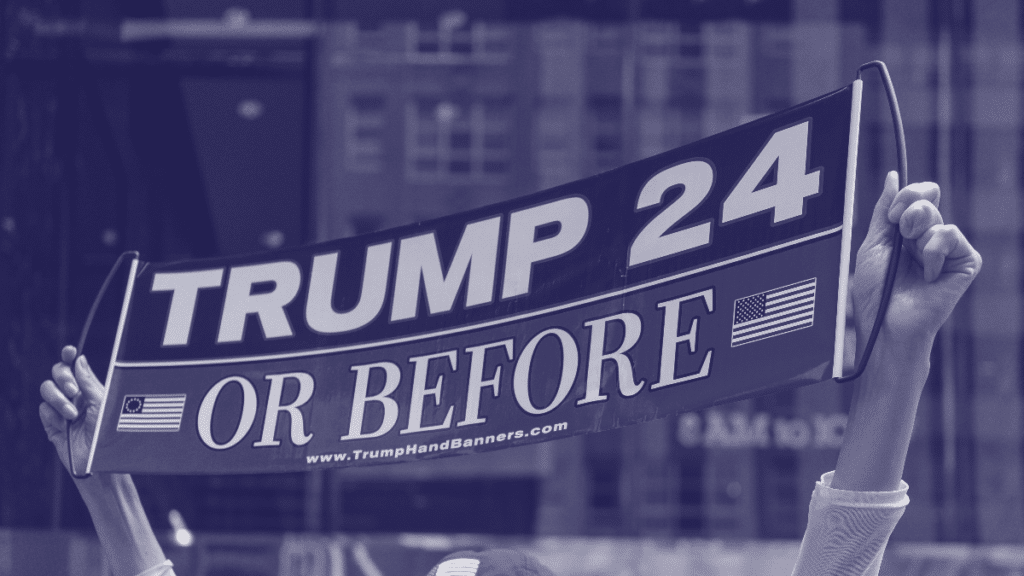

If you want to understand the 2024 U.S. presidential election, look to 2016. Despite the attempted coup on January 6th, 2021 by then President Trump and his supporters, and his continued attempts to undermine US democracy, the rule of law, and elections, the former president remains the front runner for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 2024.

One reason is that the institutions that can and should protect American democracy are again failing. Like the 2016 primaries, the Republican Party’s institutional standard bearers are running in a crowded field, providing Trump a clear path to the nomination. All the while, the Republican Party leaders that are tasked with stopping anti-democratic candidates from winning elections have denied the seriousness of January 6th and embraced authoritarianism and extremism.

The news media is also following its 2016 playbook of granting Trump billions in free media. CNN held a town hall with Trump, giving him millions of dollars in free airtime to spout lies and conspiracy theories. Wall-to-wall sensationalized coverage of Trump’s indictment also means millions in free media and less space for his Republican competitors.

While they have received less attention recently, social media platforms are also following a 2016 playbook and failing to protect U.S. democracy. Based on observations from a series of research projects on the 2020 elections, we hoped that platform companies would uphold pro-democratic principles during the 2024 elections. After the 2020 elections, our research team hailed the unmistakable steps the major U.S.-based platforms took to embrace their roles as “democratic gatekeepers.” What we meant by this is that platforms took serious steps to protect elections and the peaceful transfer of power, including creating policies against electoral disinformation and enforcing violations – including by Trump and other candidates and elected officials. And, deplatforming the former president after an illegitimate attempt to seize power was a necessary step to quell the violence.

Even if they often fell short, this means that during the 2020 election platforms embraced their important role to protect democratic processes and the integrity of elections. Civic integrity teams created more robust, democracy-focused policies against electoral disinformation, including by elected leaders, candidates, and public figures with massive followings. Content moderators began labeling false election claims, restricted their spread and engagement, and took down content designed to undermine elections through disinformation.

In the last few weeks, however, social media platforms have walked away from their commitments to protect democracy. So much so that the current state of platform content moderation is more like 2016 than 2020.

The major U.S. platforms – Meta, YouTube, and Twitter – all reinstated Trump’s account in recent months. This comes despite the fact that the former president continues to spout lies about the 2020 election and is actively working to undermine confidence in the next one. Meta seemingly did away with a policy prohibiting disinformation about the 2020 election.

In practice, these platforms appear to be taking a laissez faire approach to elections in 2024, as they did in 2016. For example, Meta claims that the risk of “real world harm” from the former president has subsided. In Meta’s announcement that it was reinstating Trump, the company specifically said that posts from Trump that violate community standards could still stand if they are “newsworthy,” an ambiguous term that means the platform itself determines “keeping it visible is in the public interest.” While keeping its policies for 2024 in place, YouTube explicitly states that election misinformation about 2022 and 2020 is now fine to spread in order to enable “public and democratic debate” and “to openly debate political ideas.” Twitter stopped caring about 2020 long ago, with a predictable flood of election lies.

Such magical thinking ignores the fact that the risk for real-world harm from election denialism generally and the former president specifically has not, in fact, subsided. For example, as tech journalist Casey Newton has repeatedly pointed out, platforms are markedly blind to how the former president and members of his party fuel attacks on and harassment of election workers.

And even if one were to agree that the “clear risk of real world harm” has somewhat receded, it is a markedly short-sighted standard. Discrediting previous elections sets the stage for discrediting future ones. And, it creates the context for partisans to see elections as existential threats if they cannot win legitimately. Trump’s election denialism, coupled with his rhetoric that his political opponents are out to “destroy America,” is a clear and present threat to U.S. democracy and a likely catalyst for violence.

Platforms seem to have the naive view that speech and expression is always in good faith and that more political speech is always beneficial since the best ideas will ultimately come out on top. This is both blind to political manipulation and the real world empirical evidence.

We know this from many other countries. As leading scholars of democracy Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman explain, authoritarian leaders “exploit deep liberal commitments to free speech” to manipulate and control media, create intimidation, discredit opponents, and undermine democratic institutions.

And the simplistic faith in the marketplace of ideas producing truth runs counter to the findings of peer-reviewed, rigorous research. Rather than exposure to false information giving people the opportunity to identify truth and discard lies, repeated exposure to falsehoods actually increases people’s likelihood to believe them. Moreover, generally people don’t objectively evaluate information they come across. Misinformation about things like the 2020 election are more likely to be believed when it supports people’s pre-existing beliefs, aligns with their social identities, and furthers their political interests.

And the idea that good information will come out on top? False information on social media platforms spreads faster than accurate news. Fact-checks – the best tool for allowing sunlight to disinfect the bad ideas and lies spreading on social media – are less effective among Republicans, likely due to the work Trump and others have done to discredit and undermine news organizations.

What does research show works in terms of limiting false information and other harmful content? De-platforming. De-platforming, the strategy that all platforms have now largely abandoned, decreases audiences for those who would take away the political freedom of others. It is sadly ironic that not too long ago the major platforms platforms recognized all of this.

Heading into the 2024 presidential election, platforms’ approach to speech falls far short of protecting against another January 6th. As we argued in advance of the 2020 cycle, at a minimum platforms should draw a bright line around election-related disinformation designed to weaken accountability at the ballot box and the public legitimacy of the vote. This includes lies about previous elections as well as future ones. And, they should refuse to give a platform to those who strategically and repeatedly espouse them in line with their political interests.

We are running out of time and chances to continue our experiment with democracy.

Authors