Platform Recommendations to Empower Influencers Driving Civic Engagement

Vandinika Shukla / Nov 14, 2022Vandinika Shukla is a civic technologist, gender and human rights policy specialist, and educator who has spent the last decade working on participatory design at MIT Media Lab’s Center for Constructive Communications to build a new civic infrastructure tackling social fragmentation, researching UX design, trust and online harassment of journalists at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, and designing national gender policy for the Sustainable Development Goals at the United Nations.

This essay is part of a series on Race, Ethnicity, Technology and Elections supported by the Jones Family Foundation. Views expressed here are those of the authors.

Amidst a thread of Instagram reels featuring reactions to pie recipes, household cleaning hacks and power washing sprays, 24-year-old Tega Orhorhoro recorded herself dropping her absentee ballot off at the county clerk’s office and encouraging her 80,000 followers to go out and vote on November 8th.

23-year-old Ronelle Tshiela, a J.D. candidate at UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law who chronicles her days as a law student in TikTok videos, told her 138,000 followers to register to vote to protect reproductive rights for women as part of the Hot Girls Vote campaign paid for by NextGen America, a Democratic political action committee and advocacy group.

And Lauryn and Steph, an influencer duo popular for their couples content, discussed student aid, pro labor and pro choice candidates and voter guides in a sponsored post by the nonpartisan Guides.Vote to the sound of Snoop Dogg with their 2.1 million TikTok followers.

As users look for trusted sources of information, social media content creators and influencers increasingly hold the large brass key to grassroots mobilization. With campaigns already leveraging them to reach young and diverse voters in a new and largely unregulated domain, it’s time for more intentional inquiry about the journeys and experiences of macro, micro and local trusted influencers serving as effective messengers for democratic participation and campaigns. Firstly, how can these influencers help underserved communities by delivering trusted information and building capacity to organize themselves? And, secondly, what tools and platform policies can both enable and protect influencers as they engage with civic and political messaging campaigns?

False and misleading information in Black, Asian-America and Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Latino communities was a significant problem ahead of the midterm elections. As in past cycles, voters of color were targeted with disinformation aimed at alienating them and suppressing turnout. Reported tactics included creating inauthentic social media accounts that posed as Black influencers. The immigrant advocacy network United We Dream Action, in partnership with Harmony Labs, studied television and online consumption habits of more than 20,000 Latinos nationwide, finding that Latinos over 36 were more likely to encounter polarizing anti-immigrant narratives than other cohorts, mainly through right-wing news sites, television and YouTube.

Similarly, online disinformation against AAPI communities during the COVID-19 pandemic manifested in violent consequences such as the March 2021 Atlanta spa shootings, as well as digital incidents such as when the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum was “zoom bombed” with racially charged images and audio messages. Furthermore, the midterm elections took place against the backdrop of a wave of new restrictive voting laws put in place since 2020. The Brennan Center for Justice reports that legislatures in 49 states introduced more than 400 bills that could restrict access to the ballot and disproportionately affect voters of color.

The new normal is a fragmented information ecosystem dominated by the loudest, most extreme voices, suffocating constructive communication and dialogue. Marginalized communities are not only at risk of targeted disinformation and online hate, but also face a void when it comes to accessing credible, trustworthy and timely information for active democratic participation.

The Power of Trusted Influencers

Unlike public figures using social media platforms– such as politicians, celebrities, athletes and artists– micro influencers have a greater capacity to form hyper-specific and hyper dedicated communities and are known for their significantly higher levels of engagement as they meticulously respond to questions and comments. Furthermore, local trusted influencers, who may not be on the platform primarily as content creators yet – like pastors or local religious leaders, teachers, local bakers, PTA members, small business owners, and community leaders – often have deeper trust within their communities that can in turn lead to higher than average conversion rates when they urge their followers to take action.

Similarly, the power of “Nano-influencers” – accounts with fewer than 10,000 followers and other small-scale influencers, whose primary occupation is rarely tied to their social media presence but who nevertheless have strong connections to their followers offline – is especially significant. These influencers are more likely to evoke the trust that people feel towards recommendations from friends and family.

“We treat content creators as experts in building community,” shared Julia McCarthy. She manages the influencer program at NextGen America, and says 60% of the influencers are creators of color.

This trust is already both being hacked to legitimize and spread harmful ideas and also, as the midterms revealed, leveraged to spread either partisan content or to enhance ‘get out the vote’ efforts. For example, Main Street One, a left-leaning political communications firm, claims it has a roster of 6.3 million micro-influencers including a national network of truck drivers, suburban mothers in Wisconsin, African-American voters in Michigan and Latino voters mobilizing around climate change in Florida. Moreover, influencers have also been a significant resource for trusted information about the pandemic as leveraged by the Beat the Virus coalition led by MIT Media Lab to deliver scientific public health guidance via social media influencers.

At its best, driving civic engagement through trusted influencers with personal connections and trust with voters is an exercise in relational community organizing at sale. But this phenomenon also comes with new threats: not only more potent disinformation campaigns, but also targeted online hate towards Black, AAPI and Latino creators. Content creators and influencers are creating new pipelines to political education, and platforms and policymakers need to prepare for both the emerging threats and opportunities in this novel domain.

There are two opportunities in the face of these emerging trends for the pursuit of safer and healthier digital media information ecosystems. Firstly, tech firms have the potential to invite and encourage new Black, AAPI, and Latino local trusted influencers with strong ties to their communities to join their platforms and expand their outreach and relationship building. As platforms seek to strengthen their election-time response, they are already operationalizing ’get out the vote’ efforts through alerts, user notifications, voter registration programs, and labels. Influencer engagement through intentional partnerships with Black, AAPI and Latino trusted influencers can be both a business opportunity and a complement to these other civic and election integrity initiatives. Secondly, platforms must make sure Black, AAPI and Latino micro and nano influencers feel equipped and safe to use their services for messaging related to electoral issues.

Platform Status Quo – A Challenging Home for Creators

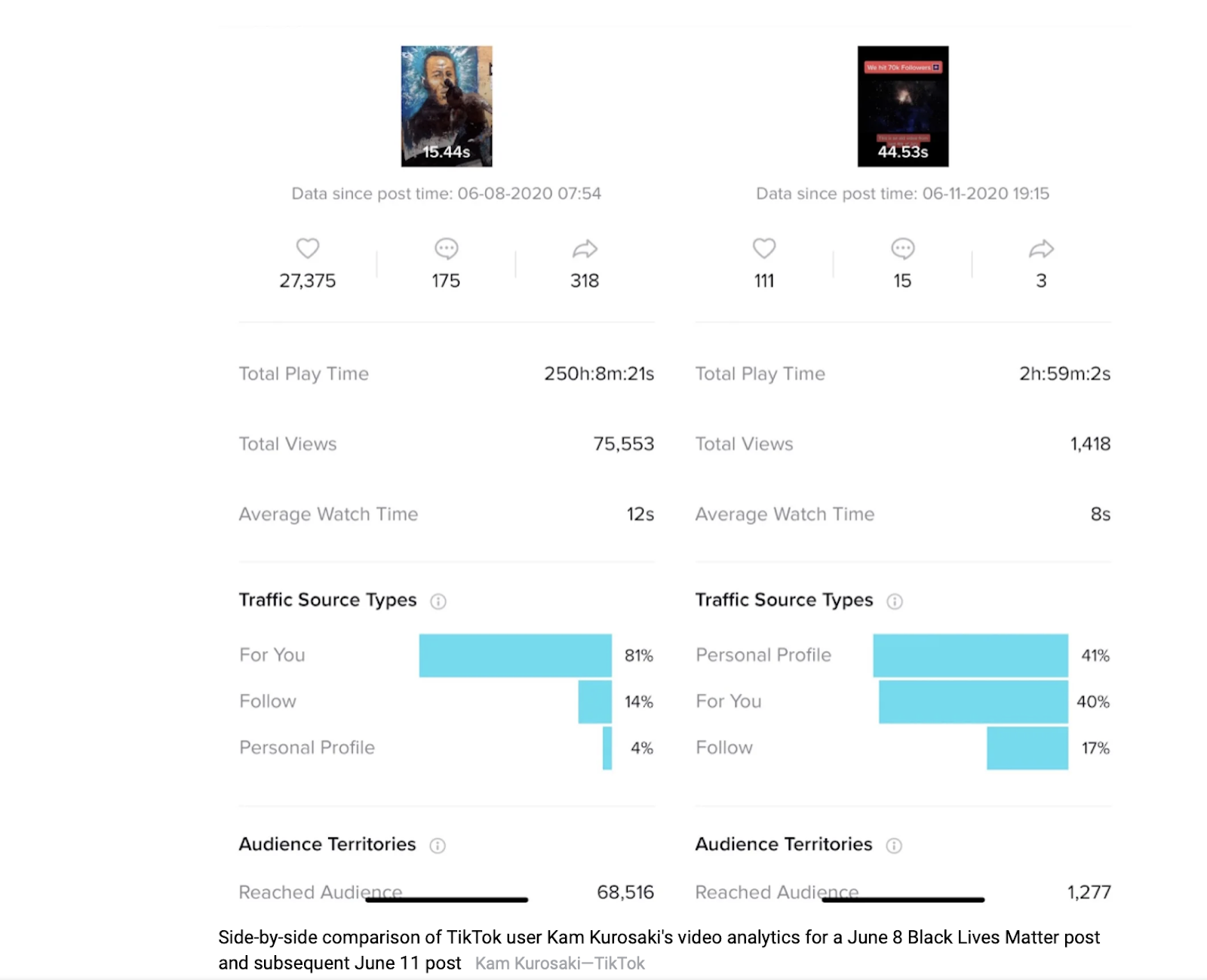

The status quo is far from hospitable to these opportunities. The practice of limiting the spread of content without notifying creators that it violates any community guidelines– shadow banning– has become a growing concern among users on TikTok, Twitter and Instagram, especially for Black creators. 19-year-old TikTok user Onani Banda told Time magazine that after two videos in which she rallied support for the Black Lives Matter movement got a much lower view count than she expected from her over 100,000 followers, and the viewership came from her personal profile implying that users would have to actively seek them out rather than receive them as followers.

While TikTok released a statement apologizing and affirming support for its Black creators and community, questions remain about what gets filtered by TikTok’s algorithm on For You feeds. In our interview with Julia McCarthy, she called for more transparency on what counts as paid content and noted that political issues like abortion often get downranked. She shared feedback from creators that posts with the hashtags ‘paid’ or ‘ad’ do worse, almost creating a penalty for influencers when they are being honest about their motivations.

At the same time, online safety for Black, Latino and AAPI creators remains a challenge. Cyberstalking, trolling, doxxing, and cyberbullying has become more violent and hateful in recent years. Black creators are demanding accountability from social media platforms for sanctioning race-based harassment. Black creator Ziggi Tyler demonstrated how TikTok’s algorithm flags keywords and phrases like “Black Lives Matter,” “Black success,” and other pro-Black text as inappropriate, with pop-up warnings instructing him to edit the language in his ads. Meanwhile, phrases like “white supremacy” passed the filters in the TikTok Creator Marketplace without further incident. According to Amnesty International’s “Troll Patrol” project, Black women were disproportionately targeted, being 84% more likely than white women to be mentioned in abusive or problematic tweets. As Twitter’s new leadership points towards loosened content rules in the future, Black creators are afraid Twitter could spiral further as a haven for racist and toxic speech. Lack of protections for and harm against Black creators has been rampant across platforms. Recently, Twitch users boycotted the streaming platform over “hate raids” – when streamers are suddenly inundated by waves of bots posting racist, sexist and homophobic messages – targeting Black, queer and disabled people.

Preparing for the Future

The future of trusted influencer-led politics for Black, Latino and AAPI communities on social media platforms requires better product solutions, stronger civic-tech partnerships and a culture shift within platform teams.

Platforms directed their attention to paid political content ahead of the midterms. But political influencer posts currently do not qualify for the stricter rules imposed by platforms on political advertising since payments to influencers by campaigns or non-profit organizations occur off-platform. This is true especially when organizations like Turning Point pumped in over $7.2 million to onboard and train over 400 creators as ‘unpaid’ brand ambassadors that get rewarded in kind, for example through travel stipends to Turning Point’s creator conferences.

Standardized disclosure practices will be essential to enable Black, AAPI and Latino creators to have clarity on platform policies as well as protections from being leveraged to spread misleading content, such as a 2020 secret social media campaign casting doubt on the integrity of the presidential election in battleground states like Arizona.

Ahead of the midterms in August this year, TikTok said it would publish educational content and host briefings with influencers and advertising agencies to ensure clarity around rules regarding paid content around elections. Along with clarity on the rules, creators need transparency on reporting processes and content moderation. Increased transparency on how algorithms operate, particularly with regards to website content amplification practices, is urgent and essential to retain and recruit creators to a safe and healthy media ecosystem.

Along with product policy, platforms need to cultivate stronger civic-tech partnerships with local trusted influencers. This means creating platform-hosted creator programs and ‘starter kits’. For example, as part of its 523 initiative aimed at supporting underrepresented creators, Snap announced its first accelerator program for emerging Black creators, marking a $3 million total investment. Similarly, Meta committed $25 million to Black creators in 2020 with a minimum of 10,000 followers on Facebook or Instagram.

Mentorship, financial resources and educational programs can level the playing field and also address the unique systemic barriers across the creator industry for Black, Latino and AAPI creators. While there is a laudable industry response to address inequity in the creator economy, we need a similar effort to promote democratic participation by influencers. This effort should include a stronger feedback loop between influencers and tech platforms on product policy, and clearer user journeys for creators. Through new and stronger partnerships with community organizations, platforms can create a healthy, safe and enabling ecosystem for potential and existing local trusted influencers.

Platforms can further empower Black, Latino and AAPI influencers with better data sharing and data training. For example Vocal for Creators introduced ‘Reader Insights’ to offer a streamlined and moderated process for readers and subscribers to leave constructive feedback on stories.

Lastly, creators need stronger communities to share knowledge and advocate for protections. Black Creators Matter, started in January 2019 as a movement, offers a networking platform for over 1000 Black content creators and a supportive forum with educational resources and professional advice. Similarly, Shade’s Black Creator Program– in collaboration with Google for Creators– offered funding, mentorship, education and a community for Black creators. With the new Influencer Agreement by the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) and the formation of The Creator Union, protections and privileges previously reserved for YouTube influencers are now being extended to a wider range of creators across platforms.

Despite these positive developments, it is clear the supply of support to new and potential influencers who share civic and political content is being eclipsed by the demand. Black, Latino and AAPI creators need increased transparency, diversity and equity backed up by platform policies and partnerships, as well as more support from civil society. With the 2024 election cycle looming, platform and policy reform needs to see sooner and act faster.

Authors