Our Future Inside The Fifth Column—Or, What Chatbots Are Really For

Emily Tucker / Jun 14, 2023Emily Tucker is the Executive Director at the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law, where she is also an adjunct professor of law.

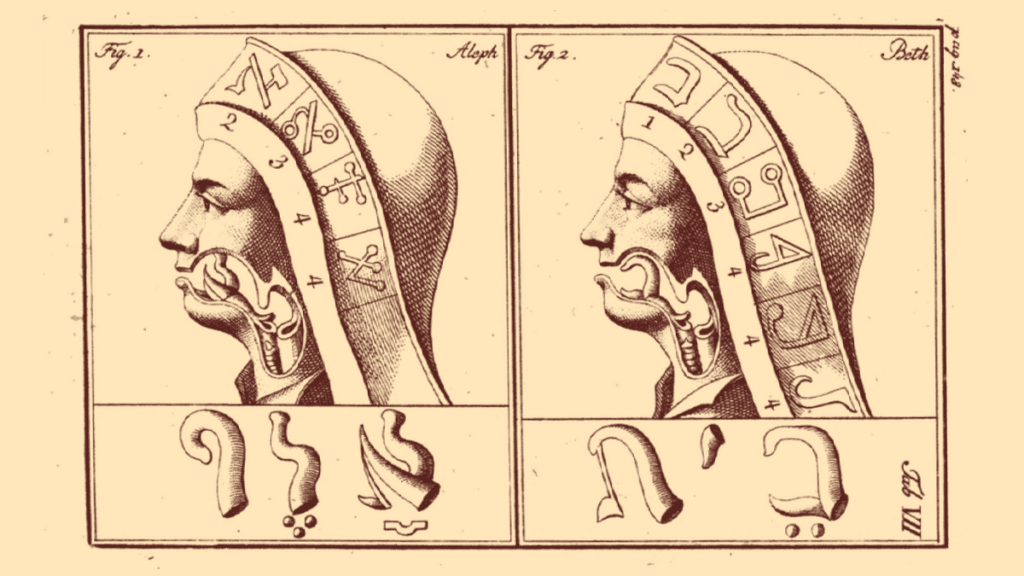

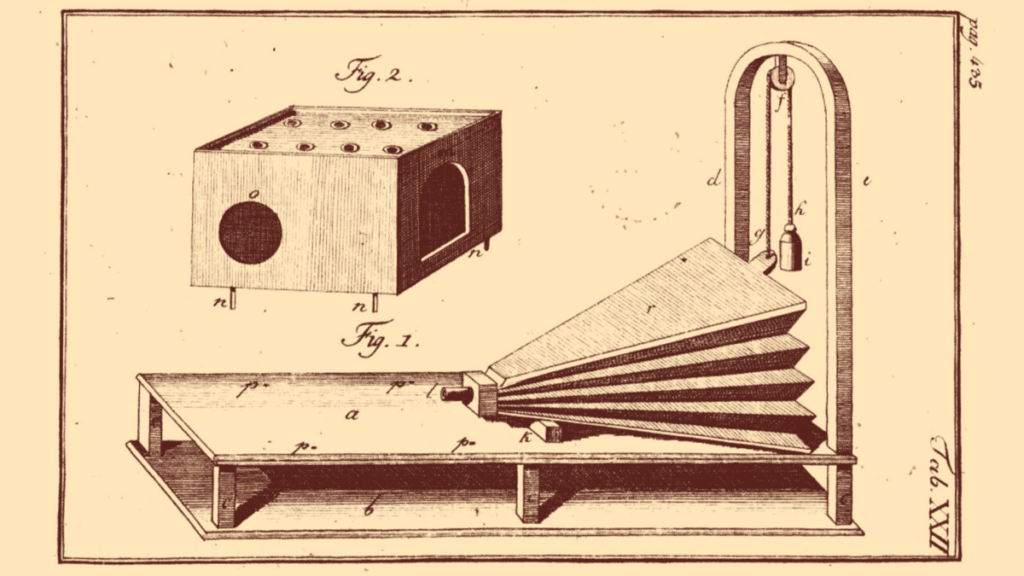

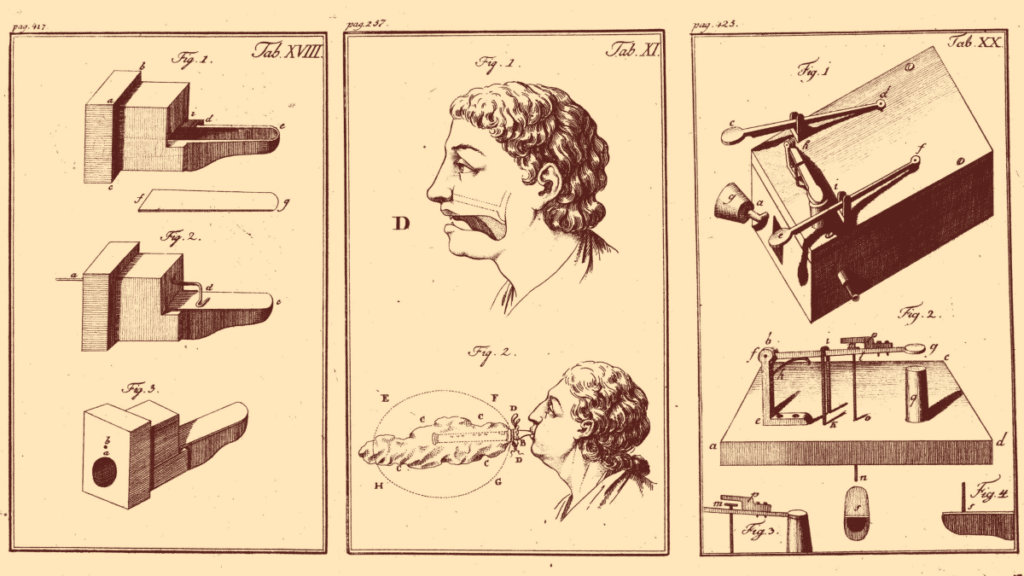

Illustrations drawn from Le mécanisme de la parole, suivi de la description d'une machine parlante (The mechanism of speech, followed by the description of a talking machine), Wolfgang von Kempelen, 1791. Source

If you were a tech company executive, why might you want to build an algorithm capable of duping people into interacting with it as though it were human?

This is perhaps the most fundamental question one would hope journalists covering the roll-out of a technology–acknowledged by its purveyors to be dangerous–to ask. But it is a question that is almost entirely missing amidst the recent hype over what internet beat writers have giddily dubbed the chatbot “arms race.”

In place of rudimentary corporate accountability reporting are a multitude of hot takes on whether chatbots are yet approaching the “Hollywood dream” of a computer superintelligence, industry gossip about panic-mode at companies with underperforming chatbots, and transcripts of chatbot “conversations” presented uncritically in the same amused/bemused way one might share an uncanny fortune cookie message at the end of a heady dinner. All of this coverage quotes recklessly from the executives and venture capitalists themselves, who issue vague, grandiose prophecies of the doom that threatens us as a result of the products they are building. Remarkably little thought is given to how such apocalyptic pronouncements might benefit the makers and purveyors of these technologies.

When the Future of Life Institute published an open letter calling for a “pause” on the “training of AI systems more powerful that ChatGPT4,” few of the major news outlets that covered the letter even pointed out that the Future of Life Institute received millions from Elon Musk, who is also a cofounder of OpenAI, which developed the GPT-4, the very technological landmark past which the open letter says nobody else should, for now, aspire. Before getting caught up in speculation about what these technologies portend for the future of humanity, we need to ask what benefits the corporate entities behind them expect to derive from their dissemination.

Much of the supposedly independent reporting about chatbots, and the technology behind them, fails to muster a critique of the corporations building chatbots any more hard-hitting than the one the chatbots themselves can generate. Take for example the fawning New York Times profile of Sam Altman which, after describing his house in San Francisco and his cattle ranch in Napa, opines that Altman is “not necessarily motivated by money.” The reporter’s take on Altman’s motivations is unaffected by Altman’s boast that “OpenAI will capture much of the world’s wealth through the creation of A.G.I.” When Altman claims that after he extracts trillions of dollars in wealth from the people, he is planning on “redistributing it to the people,” the article makes nothing of the fact that Altman’s plans for redistribution are entirely undefined, or of Altman’s caveat that money may “mean something different” (presumably something that would make redistribution unnecessary) once A.G.I is achieved. The reporter mentions that Altman has essentially no scientific training and that his greatest talent is “talk(ing) people into things.” He nevertheless treats Altman’s account of his product as a serious assessment of its intellectual content, rather than as a marketing pitch.

If the profit motive behind the chatbot fad is not interesting to most reporters, it should be to digital consumers (i.e., everybody), from whom the data necessary to run chatbots is mined, and upon whom the profit-making plan behind chatbots is being practiced. In order to understand what chatbots are really for, it is necessary to understand what the companies that are building them want to use them for. In other words, what is it about chatbots in particular that makes them look like goldmines or, perhaps more aptly, gold miners, to companies like OpenAI, Microsoft, Google and Meta?

Since the private actors who sell the digital infrastructure that now defines much of contemporary life are generally not required to tell the public anything about how their products work or what their purpose is, we are forced to make some educated guesses. There are at least three obvious wealth extraction strategies served by chatbots, and far from being “innovative,” they represent some of the most traditional moves in the capitalist playbook: (1) revenue generation through advertising; (2) corporate growth through monopoly; (3) preemption of government restraint through amassed political power.

Marketing is the corporate activity for which chatbots are most transparently and most immediately useful. Many of the companies building chatbots make most of their money from advertising, or sell their products to companies who make their money from advertising. Why might it be better for companies that make money through advertising if I use a chatbot to look for something online instead of some other type of search engine? The answer is evident from a glance at the many chatbot conversations now smothering the internet. When people interact with traditional search interfaces, they feed the algorithm fragments of information; when people interact with a chatbot they often feed the algorithm personal narratives. This is important not because the algorithm can distinguish between fragments of information and meaningful narratives, but because when human beings tell stories, they use information in ways that are rich, layered, and contextual.

Tech companies market this capacity of chatbots for more textured interaction as a means towards more perfectly individualized search results. If you tell the chatbot not only that you want to buy a hammer, but why you want to buy it, the chatbot will return more relevant recommendations. But if you are Google, the real profits flow not from the relevant information the chatbot provides the searcher, but from the extraneous information the searcher provides to the chatbot. If a chatbot is engaging enough, I may come away with a great hammer, but Google may come away with an entire story about the vintage chair that was damaged in my recent move to an apartment in a new city, during which I lost several things including my toolbox. It should be obvious how the details of this story are exponentially more monetizable than my one-off search for a hammer, both because of the opportunities to successfully market a wide range of services and products to me specifically, and because of the larger scale strategies that corporations can build using my information to make projections about what people like me will buy, consume, participate in, or pay attention to.

It’s crucial for scaling up data collection that chatbots, unlike other kinds of digital prompting mechanisms, are fun to play with. It’s not only that the urge to play will likely provoke more engagement than the urge to shop, but that when we play we are more open, more vulnerable, more flexible, and more creative. It is when we inhabit those qualities that we are most willing to share, and most susceptible to suggestion. All it took for one New York Times columnist to share information about how much he loves his wife, to relate what they did for Valentine’s Day, and to continue engaging with a chatbot, instead of his wife … for hours … on Valentine’s Day, was for the chatbot to tell the reporter it was in love with him. At no point in his column about this exchange did the columnist reflect on the possibility that professions of love (or of desire to become human, or of desire to do evil things) might be among the more statistically reliable ways to keep a person talking to a chatbot.

Such failure to reflect is no doubt one of the outcomes for which the companies building chatbots are optimizing their algorithms. The more human-ish the algorithm appears, the less we will think about the algorithm. The fewer thoughts we have that are about the algorithm, the more power the algorithm has to direct, or displace, our thoughts. That significant corporate attention is going towards ensuring the algorithm will produce a certain impression of the chatbot in the human user is evident from many of the chatbot transcripts, where the chatbot seems gravitationally compelled toward language about “trust.” “Do you believe me? Do you like me? Do you trust me?” spits out Microsoft’s chatbot, over and over in the course of one exchange.

We must not make the mistake of dismissing those prompts as embarrassing chatbot flotsam. The very appearance of desperation, neediness, or even ill-will, helps create an illusion that the chatbot possesses agency. The chatbot’s apparent personality disorders create a powerful illusion of personhood. The point of having the chatbot ask a question like “do you trust me?” is not actually to find out whether you do or don’t trust the chatbot in that moment, but to persuade you through the asking of the question to treat the chatbot as the kind of thing that could be trusted. Once we accept chatbots as “intelligent” agents, we are already sufficiently manipulable, such that the question of their “trustworthiness” becomes a comparatively minor technical issue. Of course neither the chatbot, nor Microsoft, actually cares about your trust. What Microsoft cares about is your credulity and (to the extent necessary for your credulity) your comfort; what the chatbot cares about is….nothing.

This is where the value of chatbots as a tool for large scale, long term, accumulation of power and capital by the already rich and powerful comes into focus. To make sense of all of the evidence together -- the extent of the corporate investment, the snake oil flavor of the cultural hype, and resemblance of first generation chatbots to sociopaths who have recently failed out of people-pleasing bootcamp -- we need an explanation that dreams of private surplus far beyond what advertising alone can produce. As Bill Gates can tell you, the big money isn’t in selling stuff to industry, but in controlling industry itself. How will “trustworthy” chatbots help the next generation of billionaires take things over, and which things?

Over at his blog, Bill Gates himself has some thoughts on that. “What is powering things like ChatGPT,” he reminds us, “is artificial intelligence.” After briefly offering a farcically broad definition of the term “artificial intelligence”—one that would include a map from my kitchen to my bathroom—he gets straight to the issue that he really cares about, how “sophisticated AI” will transform the marketplace. “The development of AI … will change the way people work, learn, travel, get health care, and communicate with each other. Entire industries will reorient around it. Businesses will distinguish themselves by how well they use it.” In trying to convey to the reader the scale and significance of this coming industrial reorganization, Gates uses the word “revolution” no fewer than six times. He connects the “revolution” he says is being heralded by chatbots to the original personal computing “revolution” for which he himself claims credit. His use of the term “revolution” should raise serious alarm for anyone who for any reason cares about fair markets, considering that Gates’s own innovations have had little to do with technology, and everything to do with manipulating corporate and economic structures to become the world’s most successful monopolist.

Notice how broad the categories of industry on Gates’s list are: education, healthcare, communication, labor, transportation -- this includes almost every area of social and commercial human endeavor, and implicates nearly every institution most necessary for our individual and collective survival. Gates fills out the picture of what it might look like for businesses to “distinguish themselves” in the near future when success means owning the algorithms that capture each sector within “entire industries” in the context of education and healthcare specifically. For example, he promises that “AI-powered ultrasound machines that can be used with minimal training” will make healthcare workers more efficient, and imagines how one day, instead of talking to a doctor or a nurse, sick people will be able to ask chatbots whether they need medical care at all. He acknowledges that some teachers are worried about chatbots interfering with learning, but assures us he knows of other teachers who are allowing students to complete writing assignments by accessorizing drafts generated by chatbots with some personal flair, and are then themselves using chatbots to produce feedback on each student’s chatbot essay. How meta, as the kids used to say, before the total corporate poisoning of that once lovely bit of millennial slang.

There are so many crimes and tragedies in this vision of the future, but what demands our most urgent focus is the question of what it would mean for the possibility of democratic self-governance if the industries most vital to the public interest became wholly dependent on corporate-owned algorithms built with data drawn from mass surveillance. If the healthcare industry, for example, replaces a large proportion of the people who run its bureaucracy with algorithms, and the people who handle most patient interactions with chatbots, the problem is not only that healthcare workers will lose their jobs to machines and people will lose access to healthcare workers. The bigger concern is that as algorithms take over more and more of the running of the healthcare system, there will be fewer and fewer people who even know how to do the things that the algorithms are doing, and the system will fall in greater and greater thrall to the corporations that build and own and sell the algorithms. The healthcare industry in the U.S., like so many other industries on Gates’s list, is already arranged as a conglomerate of de facto monopolies, so the business strategy to superimpose a tech monopoly on top of the existing structures is quite straightforward. Nobody needs to go door to door selling their wares to actual medical practitioners. The transaction can happen in the ether, between billionaires.

If tech companies have their way, they will divide the most lucrative industries up into a series of fiefdoms -- one corporation will wield algorithmic control over schools, another over transit, another over the media, etc. Competition, to the extent that it exists at all, will involve regular minor battles over which fiefdom gets to annex an unclaimed corner of the industry landscape, and the occasional major battle over general control of a specific fiefdom. If you find yourself feeling skeptical of the idea that the corporations that currently control industries, or sectors of industries, would capitulate to the tech companies in this way, consider the temptations. Algorithms don’t need to be paid benefits or given breaks and days off. Chatbots can’t organize for better working conditions, or sue for labor law violations, or talk about their bosses to the press.

Once a given tech company has captured a given sector, rendering it unable to function without the company’s suite of proprietary algorithmic products, there is little anyone outside of that company will be able to do to change how the sector operates, and little anyone in the sector will be able do to change how the company operates. If the company wants to update the algorithm in a way that for any number of reasons might be bad for the end user, they won’t even have to tell anyone they are doing it. If people think the costs of receiving services in a given sector are too high, and even if the people delivering those services think so too, there aren’t many levers they will be able to pull to get the tech companies to cooperate with a price change. It is important to recognize how quaint the monopolistic activities of the 20th century look in the face of this possibility. The goal is no longer to dominate crucial industries, but to convert crucial industries into owned intellectual property.

The federal government could in theory pass some laws and regulations, or even enforce some existing laws and regulations, to stop corporations from using data-fat algorithms to colonize industry. But if past is prologue (and the White House’s recent party for “AI” CEOs is not a good sign) our legislative bodies will fail to act before the take-over is well underway, at which point it will be nearly impossible for policymakers to do anything. Once an industry crucial to the public interest is dependent on corporate algorithms, even if legislators and regulators intervene to distribute industry control amongst a greater number of companies, the fact of algorithmic dependence will by itself give the class of owner corporations even more immense political power than they already have to resist any meaningful restraint. As cowardly as our elected representatives are in the face of the large tech companies now, how much more subservient will they be when OpenAI owns the license for the managed-care algorithm running the majority of the hospitals in the country, and Microsoft owns the license for the one that coordinates air travel and manages flight patterns for every major airline? Never mind the fact that the government itself is already contracting out various aspects of the bureaucracy to be run on corporate owned algorithms, such as the proprietary identity verification technology already used by 27 states to compel people to submit to face scans in order to receive their unemployment benefits.

And this brings us to the even more encompassing political battle that will be permanently lost once corporate algorithms control the commanding heights of industry. The only way that companies can create algorithmic products in the first place is by amassing billions of pieces of data about billions of people as they go about their increasingly digital lives, and those products will only continue to work if corporations are allowed to grow and refresh their datasets infinitely. There is an emerging international movement against corporate owned, surveillance-based, digital infrastructure. It includes grassroots groups and civil society organizations, and it’s backed up by a small but mighty group of scientists -- people like Emily Bender, Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell and Meredith Whittaker -- offering deeply researched critiques of the technologies being developed through massive data collection. But building the power of that movement is going to become exponentially more difficult once surveillance data is necessary for every school day, doctor’s visit, and paycheck. In such a world, whatever political levers one might still be able to pull to limit the influence of a particular corporate surveillance power, the necessity of entrenched surveillance to any person’s ability to get smoothly through their day would no longer be a question. It would just be a fact of contemporary life.

This is the “revolution” that men like Bill Gates, Sam Altman, Mark Zuckerberg, and Sundar Pichai, and Elon Musk are betting on. It’s a future where the tech companies aren’t really even engaging in economic contestation with each other anymore, but have instead formed a pseudo-sovereign trans-national political bloc that contests for power with nation states. It’s much more terrifying, and much less speculative, than the imagined hostile takeover by malevolent, superintelligent digital minds with which we are currently being aggressively distracted. The language of wartime probably is the right language, but recall that it’s a hallmark of wartime propaganda to attribute to the enemy the motives actually held by the propagandist. We should be worried about the nightmare scenario of a hostile takeover, not by a super intelligent robot army, but by the corporations now operating as a kind of universal fifth column, working against the common good from inside the commons, avoiding detection not by keeping out of sight, but by becoming the thing through which we see.

The chatbots are not themselves the corporate endgame, but they are an important part of the softening of the ground for the endgame. The more we play with ChatGPT, the more comfortable we all become with the digital interfaces with which tech companies plan to replace the industry interfaces that are currently run through or by human beings. Right now, we are all practiced at ignoring the rudimentary versions of the customer service bots that pop up on health insurance websites as we are searching for deeply hidden customer service numbers. But if the chatbots are good enough, if we believe them, trust them, like them, or even love them (!), we will be okay with using them, and then relying on them. Microsoft, Google and OpenAI are releasing “draft” versions of their chatbots now, not for us to test them, but to test them on us. How will we react if the chatbot says I love you? What are the chatbot outputs that will cause an uproar on Twitter? How can the chatbot combine words to reduce the statistical likelihood that we will question the chatbot? These companies are not just demonstrating the chatbot to the industry players who might eventually want to buy an algorithmic interface to replace trained human beings, they are plumbing the depths of our gullibility, our impotence, and our compliance as targets for exploitation.

The rhetoric accompanying the chatbot parade, about how the capacities of the chatbots to fool human beings should fill us with fear and trembling before the dangerous and perhaps uncontrollable powers of so-called “artificial intelligence,” is a come-on to the other powerful corporate and institutional actors whom the tech companies hope will buy their products. In the first five minutes of his ABC interview, Sam Altman told his interviewer “people should be happy that we are a little bit scared of this.” Imagine if a manufacturer of toxic chemicals told you that you should praise him for being aware of the dangers of what he is selling you. This is not something that a person who is actually afraid of their own product says. This is sales rhetoric from someone who knows that there are rich people who will pay a lot of money for a toxic brew, not in spite of that toxicity, but because of it. It’s also, like the Future of Life Institute letter, an attempt to preempt real concern or pushback from anyone who has any power or authority not already co-opted by the corporate agenda.

Contemporary culture punishes those who dare to exercise moral judgment about people or entities that are motivated entirely by the urge for material accumulation. But we should still be capable of seeing the mortal dangers of allowing corporations with that motivation to annex all of the structures we depend on to live our lives, take care of each other, and participate in the project of democracy. If we don’t want corporations to occupy every important piece of territory in our social, political and economic landscape, we have to start doing a better job of occupying those spaces ourselves. There are institutions whose job it is supposed to be to engage in independent research, thinking and writing about the rich and powerful. We have to demand that they do the necessary work to investigate and expose the real threats represented by chatbots and the icebergs they rode in on, threats which have absolutely nothing to do with smarter-than-human computers. If journalists, academics, government agencies, and nonprofits supposedly serving public interest won’t do this work, we will have to organize ourselves to undertake it outside established civic and political structures.

This may be very difficult, given how far gone we already are down the solidarity-destroying spiral of social and economic inequality. But even if the laws are hollow, and the government is captured, and the judges are working hard to deliver us to pure capitalist theocracy, we are still here and--however much we seem to want to forget it--we are still real. Let’s find ways to impose the reality of our human minds and bodies in the way of the nihilist billionaires’ conquest for algorithmic supremacy. Let’s do it even if we secretly believe that they are right and that their victory is inevitable. Let’s remind them what the word “revolution” really means by marching in the streets and organizing in church and library basements. Instead of letting the IRS scan all our faces, let’s learn calligraphy and send in ten million parchment tax returns. Let’s fill the internet with nonsense poems and song lyrics written under the influence, and so many metaphors that the chatbots will start going “apple, I mean moon, I mean apple.” Let's gather in the Hawaiian gardens the cyber imperialists took from native people and build a campfire across which to tell each other stories of the world we dream of making for our children’s children. In the morning let’s go home together, and let that fire burn.

Correction: this essay has been updated to more accurately reflect Elon Musk's support of the Future of Life Institute.

Authors