One Year Into Biden's AI Order: Will a New President Change Course?

Carolyn Wang / Oct 30, 2024

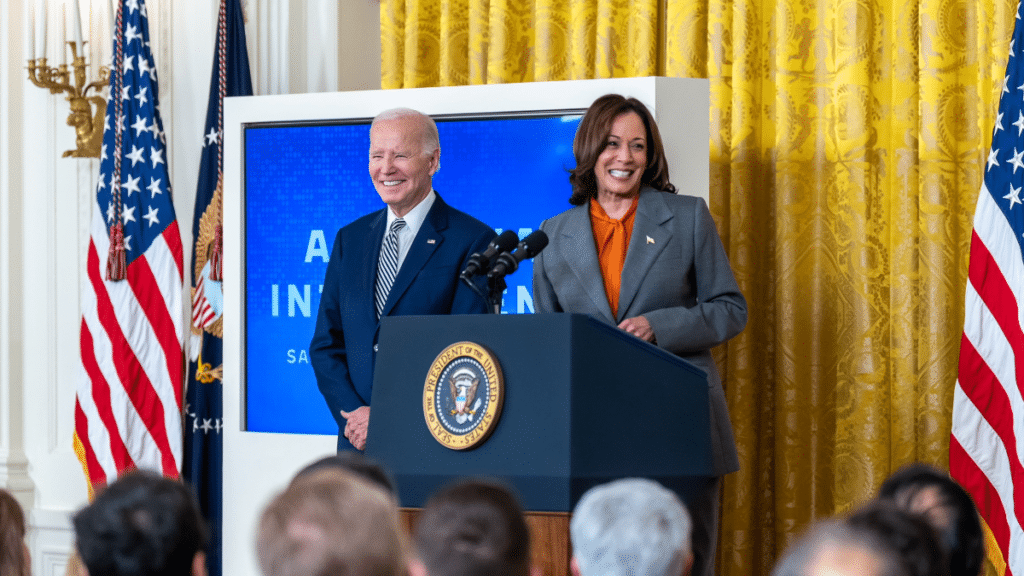

US President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris at a White House ceremony to sign an executive order on artificial intelligence, October 30, 2023. Source

With the November US presidential election looming, it’s important to consider what the outcome might mean for the nation’s future approach to AI policy. It’s clear from the policy platforms released at the Republican and Democratic National Conventions that the parties have very different perspectives on how to address AI. Whether former President Donald Trump returns to the White House or Vice President Kamala Harris gets promoted to the Oval Office will have a significant impact on what the federal government decides to do in what many regard as a crucial period for the governance of these emerging technologies.

A key question is whether the Biden-Harris administration’s “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence,” issued last October, will survive or if a second Trump administration would deliver on its promise to rescind the order, which the GOP policy platform calls “dangerous.” The battle over the Executive Order reveals much about how the parties appear to be thinking about AI and the role of the executive branch in setting the course.

Justifications and Criticisms of the AI Executive Order: the Defense Production Act

In mapping the dispute over the Executive Order, one point of entry is not its substance but rather the method by which it was introduced. In an effort to “ensure and verify the continuous availability of safe, reliable, and effective AI,” President Biden issued the Executive Order under the expanded authority of the Defense Production Act of 1950 (DPA) — a statute issued in the aftermath of the Korean War in an effort to give the president “a broad set of authorities to influence domestic industry in the interest of national defense.” In recent years, Presidents have invoked it for various purposes other than wartime defense. For instance, the DPA was invoked by both Presidents Trump and Biden to bolster the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic through the increased production of critical medical supplies and other pandemic response initiatives.

The Biden AI Executive Order, which foregrounds the “security risks” posed by AI, can be read as primarily a national security order, and last week it spawned a substantial national security memorandum. However, critics of the Executive Order argue that issuing it under the DPA is an example of executive overreach. In March 2024, the Republican-led House Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and Government Innovation hosted a hearing titled “A White House Overreach on AI, where multiple conservative scholars testified to that effect. The R Street Institute’s Adam Thierer said in his opening testimony that “the order flips the Defense Production Act on its head and converts a 1950s law meant to encourage production into an expansive regulatory edict intended to curtail some forms of algorithmic innovation,” while the Cato Institute’s Jennifer Huddleston testified that the Executive Order invokes the DPA not to respond to a security crisis, “but rather to require innovators of AI products deemed high risk that they both notify the government and submit to government-run ‘red teaming’ regarding the potential risks.” Neil Chilson, head of AI policy at the Abundance Institute, testified that the DPA does not allow the President to “micromanage industries on an ‘ongoing’ basis.”

These perspectives contrast with the views of those who support the Executive Order, who see it as simply another measure to combat a rising threat to national security, similar to the way COVID-19 was framed as a national security threat back in 2020. As Nicol-Turner Lee, senior fellow and director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, put it in her testimony, the Executive Order frames AI as “both an asset and concern for our national security interests.”

In general, there is little consensus as to when the DPA has been misused and when it hasn’t been. For example, when President Obama invoked the DPA in 2012 to financially support his Blueprint for a Secure Energy Future, he drew ire from Republicans, who accused his administration of using the funding to unlawfully drive his renewable environmental policy agenda at the expense of national security. Meanwhile, President Trump’s invocation of the DPA in 2020 to combat national shortages in the meat supply drew equal criticism from Democrats, who condemned the executive order for the health risks it posed to meatpacking workers across the country. The disagreement over the method by which the AI Executive Order was introduced hangs over the broader debate about its substance.

Trump vs Harris: Broader Trends with Respect to AI Executive Orders

Putting aside concerns about the legal authority under which it was introduced, how does the Biden-Harris administration compare to the Trump administration’s approach to AI governance?

Presidents Biden and Trump appear to have employed alternate — although not mutually exclusive — methodologies in arriving at their approach to AI governance. The Biden administration has largely addressed AI concerns through a balance of (a) risk mitigation in the form of increasingly detailed, overarching regulatory guidance through measures such as the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and the Executive Order and (b) innovation-focused directives via the establishment of AI resource pilots and tech career pipelines.

Former President Trump, on the other hand, approached AI with innovation squarely in target and concerns over regulation on the backburner. During his 2017-2021 term, well before OpenAI’s ChatGPT and today’s advanced LLMs became mainstream, Trump signed two of his own AI Executive Orders in Feb. 2019 and Dec. 2020. Together these two executive orders doubled non-defense research and development spending on AI in areas of “core” research; released a 5-Year federal STEM Education Strategic Plan; established the National AI Research Institutes with $1 billion in funding alongside the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Department of Energy (DOE); and issued a plan for AI technical standards and regulatory principles that emphasized limiting regulatory overreach while promoting trustworthy technology.

What Revoking the Biden-Harris AI Order Might Mean

In the event that the Biden AI Executive Order is rescinded without the passing of meaningful legislation in Congress, experts warn about potential ramifications for the future of ethical AI development, a potential departure from protections surrounding civil liberties and human rights, and an apparent departure from the public consensus.

An executive order can be rescinded as soon as an incumbent president enters office, either by issuing a new EO or modifying the original one. For example, Biden rescinded six Trump-era regulations during his first day in office, and Obama did the same with Bush’s executive order on presidential records. Should the current AI EO be rescinded, the main aspects that would be affected would include long-term goals established by the document, as Biden’s current AI EO can be split into two broad directives: ones that are time-bound and ones that are not.

Already, the administration has taken action on time-sensitive directives, releasing reports at the 90-day mark (January 29, 2024), 180-day mark (April 29, 2024), and 270-day mark (July 26, 2024). The end of this month will also usher in the 365-day deadline for the EO. Key initiatives that have been implemented since October 2023, most of which fall into the categories of managing risks to safety and security, AI innovation, and advancing US leadership, include:

- A successful pilot of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR), which provides computational resources for US researchers and educators. Notable contributions include increased access to cloud and advanced computing resources, access to AI models, and AI educational materials for students in partnership with governmental agencies (i.e., NSF, DOE, NASA) and corporate partners (i.e., AWS, Microsoft, Meta, OpenAI Anthropic, Nvidia);

- Comprehensive AI risk assessments submitted to the Department of Homeland Security by nine federal agencies — including the Department of Defense, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Treasury, and the Department of Health and Human Services;

- Released guidance to help federal contractors and employers comply with worker protection laws in relation to AI deployment in the workplace and non-discriminatory practices in the housing sector;

- Launching of a global network of AI Safety Institutes and the Department of State’s “Risk Management Profile for AI and Human Rights,” which was developed in close coordination with NIST and the US Agency for International Development;

- The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) finalized memo, “Advancing Governance, Innovation, and Risk Management for Agency Use of Artificial Intelligence,” on March 28, 2024, which required the appointment of Chief AI (CAIO) Officers across federal agencies within 60 days, alongside guidelines released by the AI EO and draft memos earlier last year; and

- The release of the National Security Memorandum referenced above and the complementary Framework to Advance AI Governance and Risk Management in National Security.

On today's October 30 anniversary of the order, the White House released a summary of its accomplishments. More comprehensive reports of the AI EO’s accomplishments to date can be found in released White House fact sheets, online summaries, and the 14110 Tracker, which is maintained by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford RegLab, and Stanford Center for Research on Foundational Models. Detailed timelines of the AI EO’s requirements have also been mapped out by the Bi-Partisan Policy Center and Ernst and Young LLP.

Aspects of the AI EO that will most likely be affected by a potential rescission, primarily due to the long-term nature of their directives, include efforts at supporting a sustainable AI Talent Surge, increased funding for federal AI teams and departments, and initiatives set in place at the 450-day (Jan 22, 2025), 500-day (March 13, 2025), and 650-day (Aug 10, 2025) marks since the EO’s release. Some of these include digital content authentication efforts, global technical standards for AI development, and the NSF Director’s requirement for establishing four new National AI Research Institutes.

The potential rescinding of the AI EO may also affect the future sustainability of Chief AI Officers (CAIOs) positions within various departments, but the OMB memo detailed previously provides an additional layer of policy implementation beyond the original EO’s directive.

Some organizations that support repealing the Executive Order include lobbyist groups and industry organizations like NetChoice — a trade association of online businesses that includes large social media companies like Meta and Google — which argues that the Order is a “back-door regulatory scheme” that hurts innovation and puts the US at a disadvantage against competitors like China. Similarly, conservative think tanks and Republican lawmakers have aligned with the need to rescind it.

But in other corners, the Biden Executive Order has generally been viewed as a proactive step towards re-asserting US leadership in AI development and governance, despite some concerns over concrete implementation strategies and regulatory burdens. Experts at the Atlantic Council and Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) have asserted that the Executive Order is a welcome step towards encouraging responsible private sector innovation, increasing security in AI systems, and establishing an AI ethics framework in the US for the next decade.

Is What Voters Want a Factor?

As a last note, it’s worth highlighting that on the whole, US voters appear to want more AI regulation, not less. And, the different approaches of the two Presidents are not necessarily congruent with the views of the voters who identify with their respective parties.

- In a recent poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, Republican-voting citizens were about 1.5 times more likely than Democrats to express reservations over new AI technologies (45% to 31%). Individuals who leaned towards the GOP also expressed more negative views towards AI-enabled human processes such as speech recognition, disease detection, game playing, and “food-growing.”

- A Tech Policy Press/YouGov poll conducted in July also found more enthusiasm for AI regulation amongst Democrats than Republicans, but still a majority of those that identify as Republicans express interest in more regulation of the technology.

- A recent poll conducted by the AI Policy Institute found that “75% of Democrats and 75% of Republicans believe that ‘taking a careful controlled approach’ is preferable to ‘moving forward on AI as fast as possible.’”

- In a Gallup poll conducted late last year, nearly 40% of Americans believe AI will do more harm than good (compared to the 10% who believe the opposite), and most Republicans and Democrats also prefer some kind of broad AI regulation.

What will happen beyond November is anyone’s guess. But the possible decision point on the future of the Executive Order could serve as a defining moment for US AI governance. Whether political leaders will satisfy the public’s desire for both safety and progress remains to be seen.

Authors