New Studies Shed Light on Misinformation, News Consumption, and Content Moderation

Prithvi Iyer / Oct 4, 2024As election day approaches in the United States, there is growing concern about the integrity of the information environment and whether social media platforms are adequately prepared to address various challenges. At Tech Policy Press, we often look towards emerging science on this issue to better understand the scope of the problem and solutions that can mitigate risks. In recent weeks, new research has emerged that shows why and how people believe falsehoods on social media, the extent to which negative news is more likely to spread via the platforms, and whether there was political bias in content moderation on social media circa 2020.

Small subset of “receptive” users with extreme ideologies are more likely to believe misinformation

Previous research has shown that mis/disinformation undermines public trust and exacerbates online polarization. However, there is considerable debate regarding the extent of its impact. While past research provides insight into the scale and prevalence of online misinformation, many studies do not distinguish whether users actually believed the misinformation they encountered online.

A new study by multiple researchers at NYU, Stanford, Princeton, and the University of Central Florida tried to address this research gap by studying which users are more likely to believe the misinformation they see online. The researchers developed a novel methodology, combining Twitter data collected between November 18, 2019, and February 6, 2020, with real-time surveys to estimate exposure to misinformation and the likelihood of believing it to be true.

“What is particularly innovative about our approach in this research is that the method combines social media data tracking the spread of both true news and misinformation on Twitter with surveys that assessed whether Americans believed the content of these articles,” said one of the study’s authors, NYU Center for Social Media and Politics (CSMaP) co-director Joshua Tucker, in a press statement.

The researchers studied 139 news stories shared on Twitter, 102 of which were rated as true and 37 of which were rated as false by professional fact-checkers. To determine whether users actually believed misinformation on Twitter, the study first determined which users were exposed to these articles based on their ideological leanings. They then employed real-time surveys, asking respondents whether they believed the news story was true or false, along with collecting demographic information. The results show that users across the political spectrum viewed false news stories. However, those with more extreme ideologies (both left and right) were more likely to believe them to be true, and these “receptive” users also tend to encounter misinformation earlier than their ideologically moderate counterparts. In fact, the study found that users who are likely to believe misinformation encounter it “within the 6 hours after an article URL is first shared on Twitter/X”.

To explore effective solutions, the researchers also conducted data-driven simulations of common platform interventions (fact-checking, downranking, etc). They found that early interventions were most effective, and visibility reduction efforts like downranking performed better than interventions like fact-checking, which seek to make users less likely to share misinformation.

“Our research indicates that understanding who is likely to be receptive to misinformation, not just who is exposed to it, is key to developing better strategies to fight misinformation online,” said Christopher Tokita, a former Princeton PhD student and one of the authors of the paper.

Those who primarily consume news via social media could be more likely to see negative content

Another new research paper authored by Joe Watson, Sander van der Linden, Michael Watson, and David Stillwell looked at whether external news stories with a negative tone are shared more widely on social media, potentially incentivizing media organizations to adopt negative language in their publications. Prior research has already demonstrated the prevalence of negativity bias which refers to the tendency to engage more with content that has a negative language. However, less is known about whether this bias shapes which news stories are shared and whether it incentivizes journalists to adopt such language for online engagement.

The researchers analyzed news articles from the Daily Mail, The Guardian, the New York Times, and the New York Post between 2019-2021 alongside social media posts referencing these articles on Twitter (X) and Facebook in that time period. They found that “negative news articles are shared 30% to 150% more to social media.” Thus, those who primarily consume news via social media are more likely to see negative content than those who do not. This is especially true for users on the political right, because the study found that negative news articles from right-leaning outlets were more widely shared on Facebook compared to left-leaning outlets.

These findings have implications for the field of journalism. As the authors note, “News sharing on social media could incentivize journalists to create more negative content, potentially leading to increased negative news exposure even for those who stay informed only using online news sites.”

Political asymmetry in sharing low-quality information may explain why right-leaning users are more likely to get suspended

Platforms have tried to address misinformation and hateful content in a variety of ways and faced backlash from both sides of the political aisle. While some believe platform interventions censor conservative voices under the garb of combating misinformation, others believe they do not go far enough. This pressure has also led Big Tech companies like Meta to reduce political content on their platforms. Given the urgency of the issue, especially in an election year, a new research paper published in Nature examines whether there is empirical evidence to support the claim that social media platforms have a political bias.

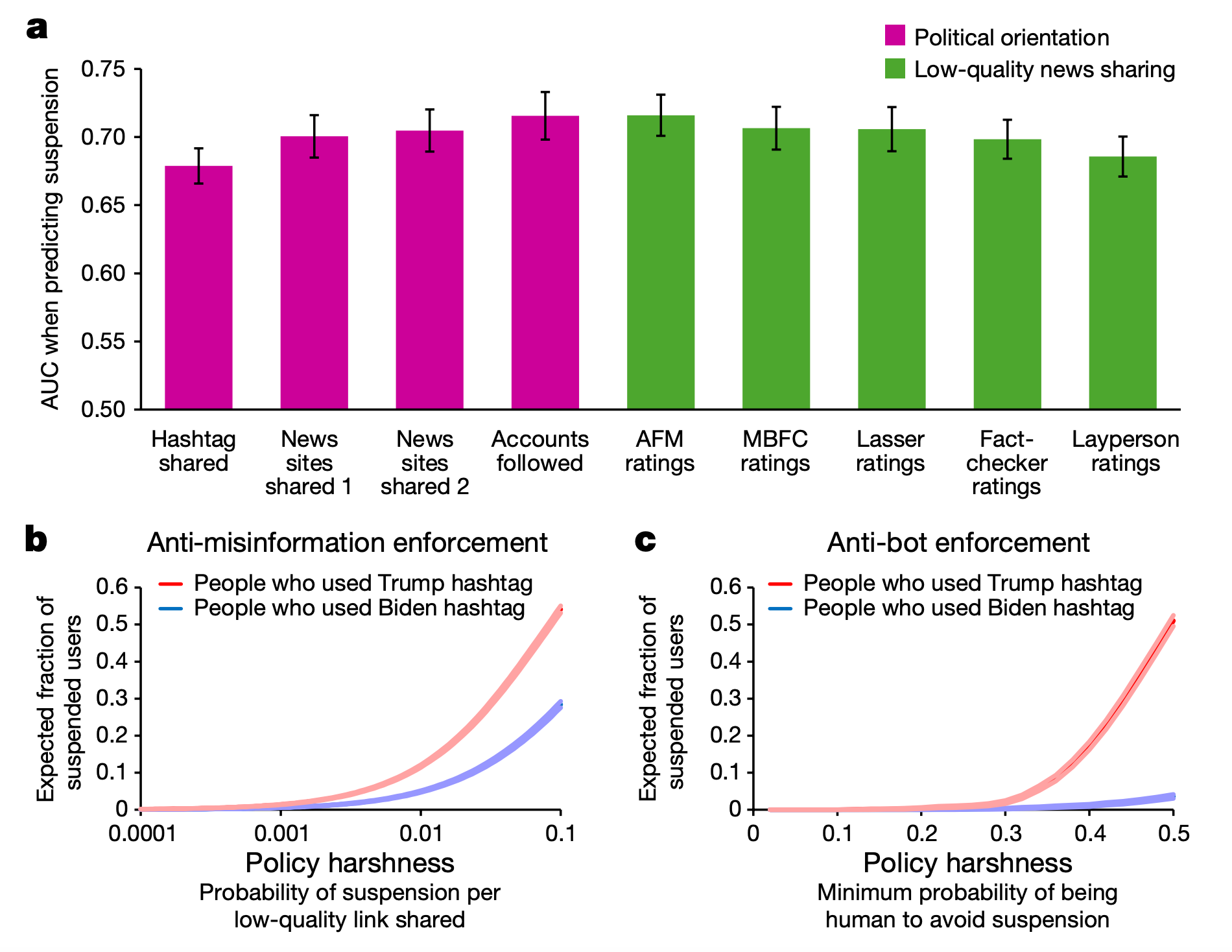

The authors analyzed 9,000 politically active Twitter accounts during the 2020 US election. The study found that accounts that shared the hashtag #Trump2020 “were 4.4 times more likely to have been subsequently suspended than those that shared #VoteBidenHarris2020.” To test whether account suspensions indicate political bias, the researchers also examined how the political orientation of users shaped their sharing of low-quality news articles online. Consistent with previous research, they found that people using Trump hashtags “shared news from domains that were on average rated as significantly less trustworthy than people who used Biden hashtags.” These results relied on independent fact-checkers who have also come under fire for allegedly having a political bias against conservatives. Hence, the researchers also assessed whether the findings are replicated if trust ratings are “generated by politically balanced groups of laypeople” and find that Trump supporters still share more low-quality news.

A chart from the study. "Political orientation is not a unique predictor of getting suspended, and politically neutral enforcement policies will lead to political asymmetries in suspension rates."

This association was also found outside the US, where a survey of 16 countries found that conservatives shared more false claims about COVID-19 compared to liberals. Thus, this research found a “consistent pattern whereby conservative or Republican-leaning social media users share more low-quality information—as evaluated by fact-checkers or politically balanced groups of laypeople.” This results in an asymmetry in enforcement. “Thus, even under politically neutral anti-misinformation policies, political asymmetries in enforcement should be expected,” the authors write. “Political imbalance in enforcement need not imply bias on the part of social media companies implementing anti-misinformation policies.”

Conclusion

Of course, the 2024 US election is in less than four weeks; these research results, all based on data from the last election cycle four years ago, are unlikely to inform much of the current debate over the role of platforms in politics or the decisions inside platforms over how best to address misinformation and thorny content moderation questions. Here’s hoping the results may nevertheless inform better platform design and policy going forward, and that the field can find ways to speed up the process of studying platform dynamics and publishing the results.

Unfortunately, platforms have made it harder for researchers to access their data, notably, with the demise of Meta’s CrowdTangle and Elon Musk’s imposition of higher fees to use the X API. This makes conducting and publishing social media research harder. Whether we’ll see such significant studies on the 2024 election cycle remains to be seen.

Authors