New Perspectives on AI Agentiality and Democracy: "Whom Does It Serve?"

Richard Reisman, Richard Whitt / Dec 6, 2024

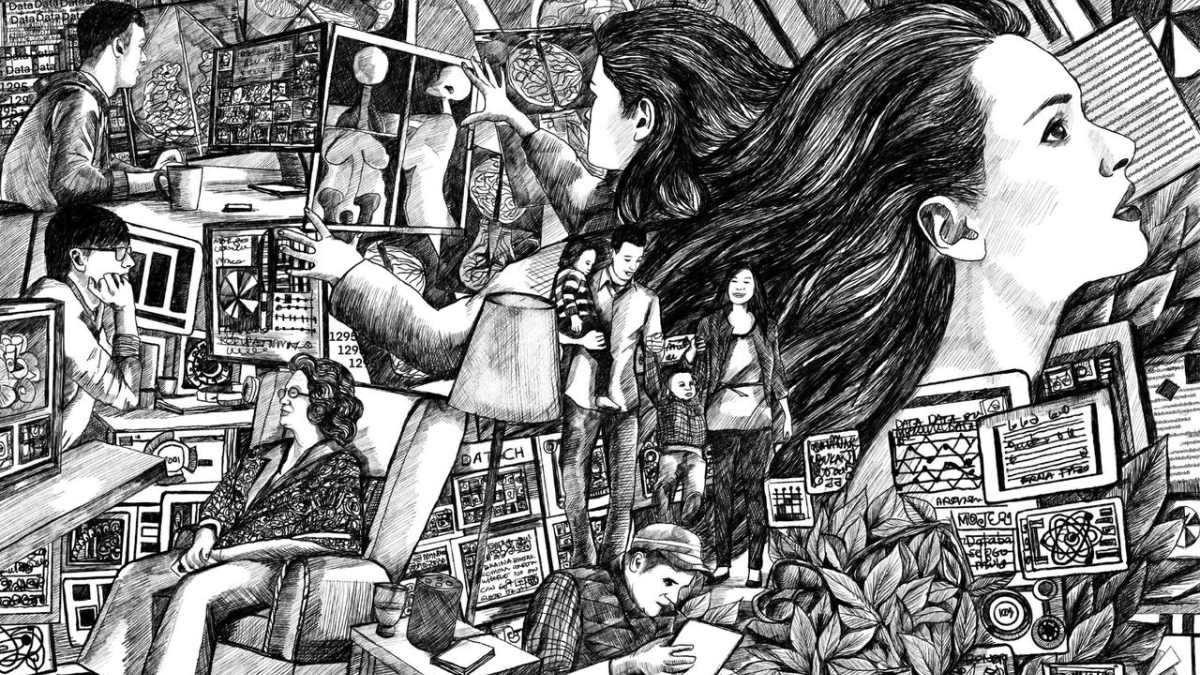

Ariyana Ahmad & The Bigger Picture / Better Images of AI / AI is Everywhere / CC-BY 4.0

Many in the tech industry expect that in the near term AI will evolve from the level of today's chatbots to more sophisticated AI agents capable of engaging in complex actions with little supervision. First, this raises the prospect that democratic freedoms will increasingly be threatened by the failure to adequately consider the essential role of personal agency in how our agents serve us. Second, beyond effects on individual agency and autonomy, lies the potential role of AI agents in the broader community and effects on the social dynamics that our humanity is built on. We suggest that new and stronger relationship framings are needed to ensure that AI serves humanity.

Our thesis is that the growing body of work on “AI ethics,” “value alignment,” “safety,” and “guardrails” raises a host of important issues, but needs to spotlight a strategic focus on the fundamental core of the threats to democracy and human freedom. These arise from how AI will increasingly shape what we know of the world, how we act on the world, and how AI acts for us. This piece synthesizes work by the two of us to propose novel governance framings along with technical approaches to help identify and remedy those challenges to human choice and autonomy.

The overarching idea presented below is that just as humanity is not monolithic but contains multitudes, our agents or assistants cannot be built as monolithic systems that are somehow aligned by their developers to serve all interests. Rather, these systems must be composed of interoperating agents that faithfully serve their users and, in doing so, negotiate a broader alignment. This must be done at both the individual and community levels. For every broadly functional AI agent or assistant system component, the essential question is, “whom does it serve?”

Further, it now seems likely there will be a dramatic realignment of US AI policy development, with reduced emphasis on regulatory guardrails – and that would have global impact. We believe the framings and strategies suggested below offer a foundation in individual agency, leavened by social mediation, that will organically enable the adaptability, resilience, and collective intelligence needed to advance human flourishing, even in times of polarization, turbulence and governmental gridlock. Thus, we suggest that solutions that build on these framings and strategies should be able to garner broad bipartisan support once these principles are widely recognized.

Two Functional Dimensions of AI Agency

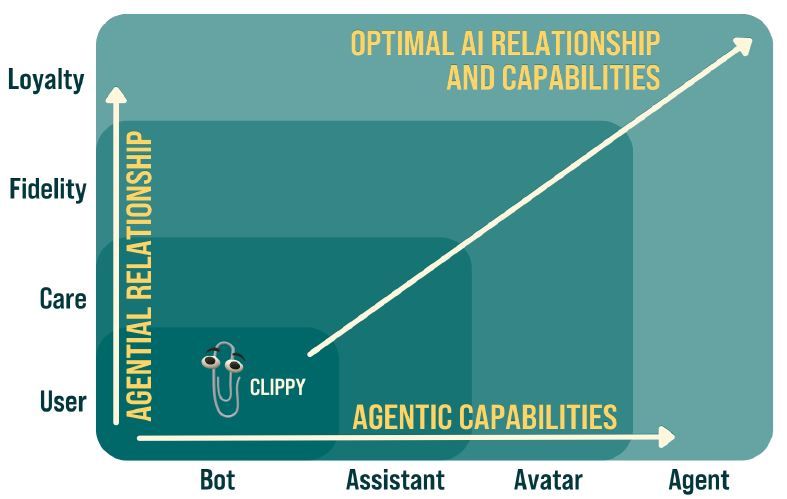

There are two basic functional dimensions of AI agency: its technical capability to accomplish tasks and the nature of its relationship to a user, as shown in this diagram:

From Richard Whitt, Reweaving the Web, 2024

- “Agenticity,” a measure of capability: According to OpenAI, an AI system’s “agenticness” is “the degree to which it can adaptably achieve complex goals in complex environments with limited direct supervision.” This is a measure of technical capability, as AIs progress from simple bots, through increasingly capable assistants and avatars, to fully autonomous agents. This has been the core focus of AI agent development, but, as explained below, on its own, this dimension is agnostic as to whom it serves and whether it supports human freedom. Without the second dimension proposed here, it could lead to highly agentic AIs that serve individuals and humanity very badly (as many fear we are heading).

- “Agentiality,” a measure of relationship: According to GLIA Foundation, an AI system’s “agentiality” is the degree to which it is actually authorized to ably represent the end user by serving as “their” agent. It can be seen as a measure of authentic human relationship, progressing from treating humans as “users” of whatever service a provider may offer, through increasingly faithful levels of care, fidelity, and loyalty to the user, as explained in this book and article. This dimension is generally neglected but is essential to “whom it serves” and to democratic freedoms. Passive “alignment,” as provided by a third party who is not bound to faithfully serve the interests of the end user, is insufficient to ensure more than a shadow of that.

Building toward optimal AI relationships and capabilities that serve individuals, society, and freedom must progress in both of these dimensions in combination.

The digital technology that can best enable agentiality is open AI-to-AI interoperability that would enable agential AI agents that faithfully serve a given user to call on or respond to other AI agents (that may or may not be fully aligned with that user) to complete desired tasks. This kind of agential alignment must apply not just when it serves the needs of AI developers, but, more importantly, to serve human “end user” and social needs. Of course, interoperability is also valuable in achieving agenticity, as well.

This deeper need of agentiality – an agent's relationship of faithful service to its user – is not technical but sociotechnical. A step toward designing for service that is agential is in a variety of proposals for “value alignment” that seek to protect AI ecosystem stakeholders. Google DeepMind frames this as a four-part (“tetradic”) relationship “involving the AI agent, the end user, the developer and society at large.”

However, conventional framings of AI alignment, guardrails, safety, and ethics look to agent developers (often very large corporations) to be the ones with the ultimate responsibility to engineer alignment for these parties, even though those parties may have diverse values and objectives that are difficult to reconcile. This approach seems bound to lead to agents that serve platform interests better than they serve those of individuals or society.

We draw in the next section on the parallel experience of social media to suggest a more open, polycentric, and emergent approach to alignment between individuals and society is needed to protect democratic freedoms in a complex and diverse society – as it has traditionally. Potential sources of such alignment to build on relate to the economic principal-agent problems of information asymmetry, authority, and loyalty, as well as the agency common law of fiduciaries and their traditional duties of good faith, care, and loyalty.

Another step toward service with agentiality has been proposed by Mozilla as “Public AI.” Public AIs might serve as a complement to corporate AIs that would expand who can build AIs in order to promote public goods, public orientation, and public use. As explained below, we suggest that AI agents that provide services that are agential – both to individuals and to communities – offer the kind of foundation needed for mixtures of public and private AI to fully achieve the individual and public interest across a diverse and open society.

Thus we offer the dimension of agentiality as the essential overarching ethical lens for the strategic design of AI agents or assistants. By focusing on the question of “whom does it serve?” all else – questions of bias, misinformation, manipulation, surveillance, and safety – becomes commentary.

The Social Pillars of Agentiality

Social media and search services rely on algorithmic agents for composing news feeds, recommenders, and search results and have already reached an illuminating level of limited maturity at scale. The lesson for AI agents is that extreme, continuing conflicts over content moderation and influence at scale demonstrate that central control of alignment by AI developers (here for freedom of speech and thought, with regard to how it impacts “society at large”) is not only illegitimate but arguably “impossible.”

Consider the strong relationship between the “social” and “media” aspects of AI and how that ties to issues arising in already-large-scale experience with social media:

- Social media increasingly include AI-derived content and AI-based algorithms, and conversely, human social media content and behaviors increasingly feed AI models

- The issues of maintaining strong freedom of expression, as central to democratic freedoms in social media, translate to and shed light on similar issues in how AI can shape our understanding of the world – properly or improperly.

A proposed response for social media has been to enable end users to select their own personal agent tools to serve them agentially, as they, not the platforms, chose. Such tools between users and platforms are commonly referred to as middleware, but a more descriptive term might be “attention guardians” that give users “freedom of impression,” the liberty to decide who to listen to, be influenced by, and associate with. There has been a growing realization within the social media world that “society at large” is not unitary but contains multitudes of communities that contradict one another and process information flows through distinct but overlapping epistemic and value cultures. Both social media and AI-based technologies should serve the relevant melange of those multitudes as a complex ecosystem that is given legitimacy by, and has influence on, individual user agency – and should address their distinct agentiality needs. As noted above for social media, top-down solutions to alignment lack the capability and legitimacy to achieve this organically emergent balance. Value alignment cannot be “designed” into a complex AI agent system that serves diverse parties – it must emerge from the interplay of agential systems, each serving the relevant array of participants in society and seeking harmony and balance among their interests.

This social mediation process and ecosystem has been neglected as we move online – it is the process humans have always used to build “social trust,” mediating how individual agency informs their epistemics, values, discourse, and actions. Technological disintermediation of this human “sociality” – replaced by an artificial sociality that is synthesized by platforms and centrally controlled AI – threatens the very nature of humanity. The failure to retain, reinvigorate, and augment processes for building individual and social trust has already wreaked havoc in our social media. It can be expected to create far greater harm to society if similarly neglected in the more advanced uses of AI that are now emerging and scaling. We should draw on ideas for re-creating social mediation processes in digital form to address current democratic, legitimacy, influence, epistemic, and value concerns in social media – to consider how that translates to other uses of AI agents.

Bringing Individual and Collective Agency to AI – Interoperation

In the online and AI realm, human-centered mediation requires support not just for individual agency but also for the application of individual agency to empower and mediate the organic human social process of collaboration/negotiation. This includes addressing and reconciling those diverse community epistemic and value cultures – and reflecting them in creating and using the AI models that will shape us, as we shape them – in ways that protect freedom and democracy. This aligns with and complements the adaptive blend of top-down and bottom-up influence (“subsidiarity”) that informs the recent “Digitalist Papers” collection, in the spirit of the Federalist Papers that shaped the founders of the US Constitution. It also aligns with movements toward “digital democracy” that would integrate collaborative deliberation processes into the online world.

At a technical level, these advances require AI-to-AI interoperation, both horizontally (between platforms) and vertically (between agents and platforms), using the kind of stacked protocol structure that enables diverse systems to interoperate in simple and well-defined ways. A key challenge will be to address the market openness and governance regimes needed to support interoperability, including creating access opportunities for personal versus institutional AIs, between and within them, and between Large Language Models (LLMs) provided by platforms and cloud services and Small Language Models (SLMs) that serve specific users or communities.

Consider some examples of personal agents – and the agential service duties of care and loyalty and the democratic freedom issues involved in protecting end users from organizations and individuals they interact with, as well as how multiple such agents might interoperate, both horizontally and vertically:

- Attention agents – as now emerging in the form of social media middleware, and evolving to AI-enhanced variations – to manage discourse and restore personal and democratic control of content feeds and recommenders, thus restoring “freedom of impression.” These can evolve with LLMs augmenting current curation, moderation, and search methods – including middleware to help in safe use of “DebunkBots” for managing mis/disinformation.

- Privacy agents – basic data fiduciary agents for managing individual personal data disclosure and usage for individual and shared private data, including support for contextual privacy criteria.

- Government and healthcare service support and obligations agents, that can support individual rights in interactions with government and quasi-government institutions.

- Consumer support agents, including infomediaries, universal shopping cart agents and vendor relationship management (VRM) agents, where individual users can bring their highly protected identity and credentials to engage directly with chosen websites and apps and personal pricing negotiation agents, to level the playing field between individuals and businesses regarding what services are provided at what price. Essentially, individuals need to be able to tell an institution, “Have your AI call my AI.”

Of course, there are many complex issues, both technical and sociotechnical, that will need to be understood and addressed.

- Not least is the likelihood that businesses may resist supporting development of personal AIs that are agential. Narrow economic incentives, unchecked by innovations like AI-to-AI interop, will favor the development of platform agents, not faithful user agents.

- Another need for interop that will likely be important is to decompose agent services into at least two levels of middleware agents that apply agenticity and agentiality to accommodate different blends of privacy/security control (as explained in this article and these slides). Examples of tight control include protecting sensitive personal data – especially multi-party personal data – via data intermediary, cooperative, or fiduciary agents versus a more loosely controlled and open diversity of user agent functions, such as composing/ranking personal or news items in feeds or recommendations.

The complexity of this undertaking should not intimidate us. How can we expect the transition from the human social structures and processes that have evolved over centuries to support our more recent experiments with open markets and democratic freedoms to be re-engineered overnight to be effective in AI-plus-human form?

Conclusions and Recommendations

- To protect democratic freedoms, AI agents must address both of the two dimensions outlined here – the currently developing dimension of capability (agenticity) and the less-attended-to dimension of relationship (agentiality, who is served).

- True “alignment” and “AI safety” will require that AI agents and related services faithfully serve – not just superficially “align” with – individual and social values.

- Faithful relationships to provide agentiality apply first to individuals, but, as well, to formal and informal collectives – as they are empowered by their individual supporters.

- This kind of faithful agential relationship is required in social media, in the form of middleware agent services – as well as in other domains, in the form of agent services that primarily serve their users, not their developers.

- Trying to nudge large corporate platforms to act in the interests of their “users” (more appropriately thought of as “clients”) and of “society” (however delineated) likely will not be sufficient to achieve more than a thin veneer of alignment with those interests.

- Public AI may be an invaluable complement to corporate AI, but rich interoperability and truly agential relationships with individual users as well as communities are essential to enabling public AI to maximize needed levels of freedom and democracy.

- Public policy should support the development and enforcement of technology, business, market, legal, and regulatory policies that enshrine and support the right to interoperable agential solutions, however sourced, that are responsible to their end users and openly extensible to address dynamically changing needs.

- Regardless of the level of public policy assertiveness, consumer and civic awareness should be educated to also drive in this direction, from the bottom up.

- Achieving these objectives will take time and will depend on a combination of policy and market forces that align user demand and developer supply to ensure high levels of agential service.

Without deep and flexible support for interoperability to enable agential relationships that faithfully serve both individuals and communities, AI agents will not be able to fulfill their promise to extend democratic freedoms and support human flourishing.

Related Reading

Authors