New Findings: Researchers Consider Elections, Hate, and Misinformation

Prithvi Iyer / Nov 5, 2024As the outcome of the 2024 US Presidential election hangs in the balance, it is worth looking at new academic research that explores the relationship between elections, political communications, and technology. This piece looks at three recent studies that provide insights into the efficacy of prebunking election misinformation using AI, the resilience and growth of online hate networks, and the shortcomings of political communication research in addressing threats of illiberalism from the far-right.

Using LLMs to combat election misinformation

According to a Pew survey, 39% of Americans believe AI will be used for “bad purposes” during the 2024 election. These fears are warranted, given widespread evidence of AI exacerbating misinformation both in the US and beyond. However, new research suggests that large language models (LLMs) can also help protect citizens from election misinformation.

Through an experimental study with 4,293 registered US voters in August 2024, Mitchell Linegar, Betsy Sinclair, Sander van der Linden, and R. Michael Alvarez found that AI-generated “prebunking” messages effectively lowered belief in false election rumors and increased confidence in election integrity. Rather than focusing on “debunking,” which seeks to address misinformation “after its already damaged public opinion,” the researchers examine the efficacy of LLMs in “prebunking,” intended to protect people from misinformation before they encounter it online. Drafting content to prebunk misinformation requires significant human effort, and given the sheer volume and variety of online misinformation, the authors sought to examine whether LLMs can help generate messages to help address misinformation at scale. “This application of artificial intelligence offers the potential for rapid, scalable production of prebunking materials tailored to emerging misinformation narratives,” the authors wrote.

Participants read a persuasive article promoting one of five common election myths and were either given an LLM-generated prebunking article (treatment group) or a neutral article on return-to-office policies (control group) prior to this exposure. Researchers measured changes in participants' belief in myths, confidence in election facts, and overall trust in election integrity both immediately after and one-week post-intervention. They found that LLM-generated prebunking reduced beliefs in election-related rumors and increased voter confidence in electoral outcomes. The findings were similar across party lines and found “no evidence of a backlash against these arguments.” The findings show that prebunking is effective and LLMs are a “powerful tool for pushing back against specific aspects of the more general reputational attack on the integrity of our elections.”

US elections and global hate networks

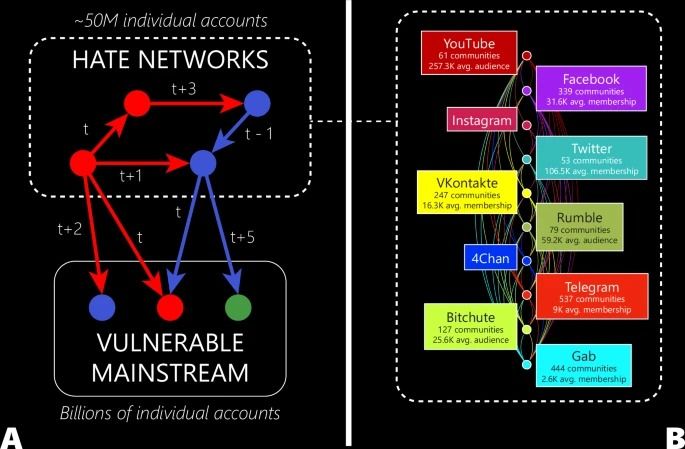

Elections can also catalyze and intensify online hate speech. A new study published in Nature by Akshay Verma, Richard Sear, and Neil Johnson explored how the 2020 US presidential election intensified global online hate networks. They found that the election cycle, which ended in a violent insurrection at the US Capitol in Washington, DC, “triggered new hate content at scale around immigration, ethnicity, and antisemitism,” with Telegram acting as a hub where such hate speech proliferated across the world. The researchers look at an emerging “hate universe,” referring to online hate communities across different social media platforms and how they interact with each other to target vulnerable groups.

Figure 1: Hate Universe Infrastructure

The researchers found a 41.6% increase in “hate links” on election day (November 3rd, 2020), which increased to 68% the day Joe Biden was declared the winner. Interestingly, they noticed that online hate groups appeared to converge into a singular and more dominant group. Between November 3rd and January 1st, 2021, the number of hate communities decreased by 19.8% while the largest hate community grew by 16.72%, indicating an evolution towards a more cohesive “hate universe” with a unified ideology. This cohesive “hate universe” contributed to a “269.5% surge in anti-immigration sentiments, a 98.7% rise in ethnically-based hatred, and a 117.57% escalation in expressions of antisemitism.”

Notably, the researchers found that Telegram played a key role in galvanizing these hate groups. In the days after November 3rd, the study found a 299% increase in online connections via Telegram, demonstrating its role as a “central platform for communication and coordination among hate communities.” Despite Telegram’s role in exacerbating hate speech, the company receives less scrutiny than major American platforms in venues such as US Congressional hearings. However, in the aftermath of Telegram CEO Pavel Durov’s arrest, the company has reportedly assured users that it will adapt its content moderation policies to comply with the Digital Services Act in the EU. This does not diminish the harm they have caused, and it's unlikely that significant changes will take place, especially in non-EU countries.

This research shows that significant offline events like a major election can trigger increases in the volume of hate speech and also recruit new people into extremist movements. The ideology underlying hate communities signals the dangers of far-right discourse and the role of online media networks in aiding and abetting its rise. The key lesson from this study as it relates to the upcoming US election is that anti-hate speech policies and interventions should take into account how hate works across platforms and on a global scale.

Is the field of political communications prepared to tackle the far-right?

The Nature authors observe an “evolution toward a more cohesive hate universe with a more unified ideology at scale,” which implies a movement that “can better amplify the spread of hate speech or coordinated actions at scale.” But is the political communication research community prepared to address the threats posed by the far-right to liberalism and democracy? A new introductory paper to a special issue of the Political Communication journal’s Forum by Curd Knüpfer, Sarah J. Jackson, and Daniel Kreiss makes the case that the field of political communication research is ill-equipped to “tackle the complexities and self-reflexive strategies” of far-right movements and actors. The authors point out that traditional frameworks fail to address how these movements exploit liberal democratic norms to advance illiberal agendas, often under the guise of free speech. Far-right movements claim to be outside the mainstream but greatly benefit from legitimization via media outlets and politicians.

To defend democracy, the research community needs more conceptual clarity on what is being studied and why. The authors believe that labeling far-right actors as “populist” or “alternative” only furthers their agendas, with the far-right often embracing these categories in their propaganda efforts. “This tactic is insidious; it uses liberalism’s own positions against itself, such as demanding a right to free speech and tolerance to promote illiberal ideas, even as they would deprive others of these privileges,” the authors write.

With a potentially volatile post-election period ahead in the US, these research results emphasize the need for scalable efforts to prebunk falsehoods, robust monitoring of hate networks, and a re-evaluation of political communication research approaches to better equip scholars and institutions to defend democratic ideals.

Authors