Mythbusting: Cybercrime versus Cybersecurity

Mallory Knodel, Wim Degezelle, Sheetal Kumar / Jan 20, 2023Mallory Knodel, Sheetal Kumar, and Wim Degezelle participated in the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) Best Practice Forum on Cybersecurity.

2022 was an eventful year for people dealing with problems in cyberspace. Cyberattacks are a hallmark of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which escalated with Russia’s full scale invasion almost a year ago. The UN First Committee continued its two parallel cybersecurity treaty processes, while a UN General Assembly ad hoc committee on a cybercrime treaty began in earnest. These events indicate the need for multistakeholder policy attention towards cyberspace now more than ever.

Cybersecurity experts, policymakers and other stakeholders must better understand the key policy differences between cybersecurity and cybercrime such that their strategies can better align with a human rights centric approach to internet governance. The best strategy is to remove policy decision making out of criminal frameworks so as to balance the implications on human rights, while promoting cybersecurity as an incentivized, normative framework that depends on cross sector collaboration and is compatible with human rights.

While policy advocates are likely already familiar with cybersecurity and cybercrime as separate concepts, they can benefit from a nuanced description of the tensions between them as a way to better understand both in context, and thus to make better policy.

Disambiguation is necessary for progress

The Internet Governance Forum (IGF), convened by the United Nations Secretary-General, is the global multistakeholder platform facilitating the discussions of public policy issues pertaining to the internet. As part of its 2015 mandate, IGF facilitates the exchange of information and identifies best practices identified by experts and academics working on various issues. Since 2014, multistakeholder IGF Best Practice Forums (BPFs) have focused on cybersecurity-related topics. Since 2018, the BPF on Cybersecurity has investigated the concept of cultures of cybersecurity, identifying the norms and values in development of these practices. As a global initiative, the IGF BPF on Cybersecurity leverages an international and cross-stakeholder approach in its operationalization of cybernorms. The BPF recognizes the significance of powerful norm promoters and of ensuring incentives as critical in global governance. Its 2020 output states that “norm development, even without results, creates socialization, which can be critical for further success.”

While the BPF framework is based on United Nations Group of Governmental Experts norms, recognizing the unique position of the UN in promoting international peace and security, the BPF adopted a political science definition of norms as a “collective expectation for the proper behavior of actors with a given identity.” There are eleven items in the 2020 analysis of international norms agreements, from which two norms come out as the most commonly referred ones: calls for cooperation to promote stability and security in cyberspace, and recognition of human rights or privacy rights online.

As identified by the BPF, our analysis also leverages a human rights focus in internet governance, with a key focus on a global perspective as both cybersecurity and cybercrime are themselves nuanced concepts that to some extent depend on geopolitical context. The following myth busting seeks to disambiguate the key policy differences between cybersecurity and cybercrime so that advocacy strategies can align.

Myth 1: Two sides of the same coin: Cybersecurity policy is proactive and cybercrime policy is reactive.

Cybersecurity is a cooperative approach which partly handles criminal law - including that which is more narrowly handled under cybercrime.

While both cybersecurity and cybercrime make references to the securitization of computational systems, these approaches are not as compatible as they are sometimes made out to be. Cybersecurity defines a technical approach to securing computational systems from attacks or errors, while cybercrime is about punishing unauthorized interference with computational systems conducted criminal intent. Sometimes cybercrime is controversially defined to include crimes committed with digital technologies. The only commonality cybersecurity and cybercrime have as concepts that they are both about security of computer systems. But, they are not dissimilar as this myth makes them out to be. Rather, cybersecurity recognises the vulnerabilities in digital systems, whereas cybercrime aims to prevent damage to these systems through punitive means (Privacy International, 2018).

In line with our reference, we can identify good practices in both these areas. Cybersecurity strategies should be based firstly on protecting individuals, devices, and networks: policies and practices should be centered on people and their rights. Secondly, cybersecurity policies should aim to establish a framework rather isolated laws, as they must encompass complementary initiatives and approaches. Specifically, these policies should identify and prioritize critical infrastructure, establish response teams for security incidents, and maintain a proper threat assessment to help in decision-making and prioritization. The last aspect of best practices in this area is the necessity of implementing comprehensive data protection laws, to safeguard against the exploitation of personal data.

Cybercrime policy, on the other hand, considers a nation’s constitution, and underpins pertinent legislation, ideally with necessary human rights protections. Further, cybercrime should be narrowly interpreted, without losing its specificity to other ‘offline’ crimes that do not necessitate the use of a computer or other digital device. Lastly, considering the rapidly changing nature of technological interception, cybercrime policy should establish frameworks narrowed to “cyber-enabled major crimes” that complement and are consistent with existing criminal law instruments, including multilateral ones. This would refer to new ways of committing the same crime like fraud or distribution of child abuse images. If such a comprehensive approach is applied in a cybercrime framework, it would allow cross border cooperation in tackling these crimes, and prevent the isolation of serious crimes under the banner of ‘cybercrime’.

This multitude that is contained in the frameworks of cybersecurity and cybercrime make it necessary for cyber policy to gather input from various stakeholders, and significantly, best practice requires civil society to play an important role in this process.

Myth 2: Considerations for human rights are equally compatible with cybercrime and cybersecurity policy.

The punitive, remedial, carceral and securitization framings of cybercrime means that human rights must be balanced between the need to ensure individual privacy versus national security interests in investigating crimes. However, within the cybersecurity framework, human rights can be more aligned with and compatible when people are placed at the center of the security of cyberspace. In cybersecurity policy making, where human rights advocates push back against the geo-politicized use of vulnerabilities and other “cyber capabilities” as tools that manipulate power in cyberspace, that tactic and others are part and parcel of sovereign states’ strategies to fight cybercrime.

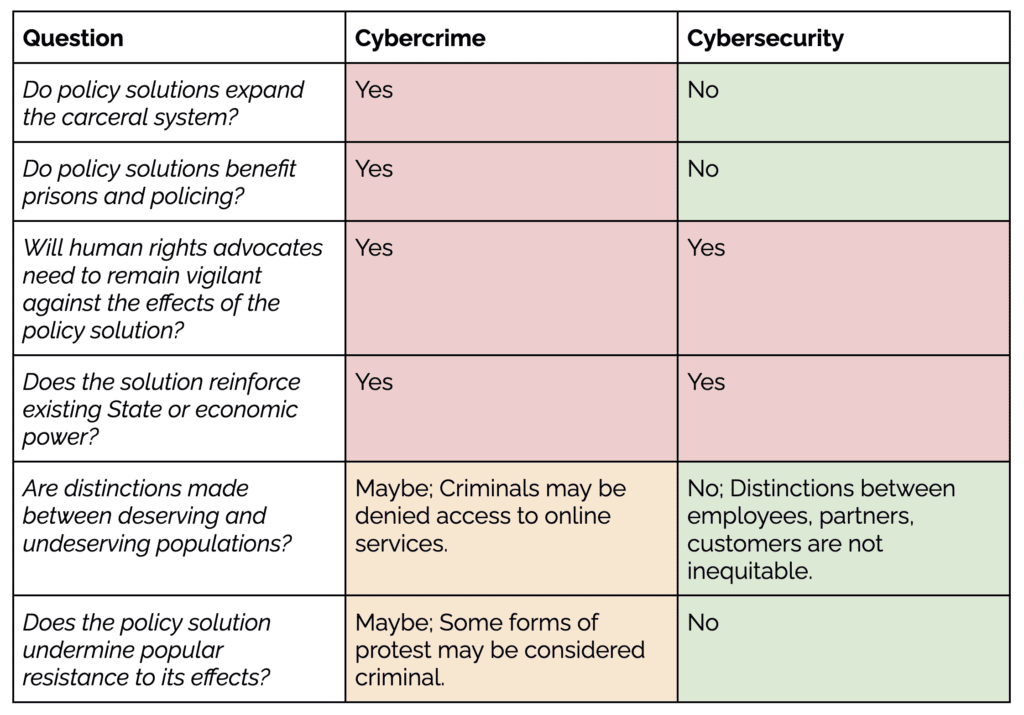

In the activist toolkit “So is This Actually an Abolitionist Proposal or Strategy?” the following questions may help define a human rights approach through contrast. The approach taken by cybercrime versus cybersecurity might be considered as such, and explained below:

Myth 3: The security of information is a consideration for both cybercrime and cybersecurity. (It’s controversial!)

It may be common for the term “information security” to be used by technical practitioners within the context of an organization as an engineering practice, but in some parts of the world it’s used as a term covering many other problems of the information space - for instance, it might reference cultural or political stability. Directly speaking, in these contexts information security can sometimes mean that information itself may be a security threat. From a human rights perspective, because of the needed balance with free expression, the term cybersecurity largely steers clear of addressing these often content driven issues.

In cybercrime, this same issue is harder to avoid due to explicit issues such as those related to copyright law. However advocates should minimize or eliminate the presence of intellectual property in cybercrime legislation because it can easily introduce content considerations in cybercrime, which unchecked as a matter of state security is at greater risk of infringing on human rights of free expression than cybercrime.

Myth 4: Countering cybercrime improves cybersecurity.

One would think that in most cases, work to counter cybercrime improves cybersecurity. However, entrenched cybercrime laws, such as outlawing security research or the development of exploit code, have been shown to negatively impact the ability of defenders to improve cybersecurity overall. When cybercrime laws are being developed, they should thoughtfully consider the impact on defenders, who often rely on the same techniques to validate and protect systems, but clearly do so with no criminal or malicious intent.

Myth 5: Cybercrime and Cybersecurity both improve with enforcement.

In the cybercrime world, we often speak of the enforcement of laws. Cybersecurity has its equivalent outcome– compliance. However, compliance is only one part of building healthy cybersecurity.

A second part is culture. Cybersecurity is so rapidly evolving that we can’t prescribe to everyone how to act online. There are some basic steps individuals and organizations can take to protect themselves, and where the goal of cybersecurity is to achieve maximum compliance. However, in the face of rapid change, cybersecurity also requires education, awareness and norms, which cannot be governed in such a way and need to be further developed to create knowledgeable citizens.

Relatedly, one aspect of this elaboration on the norms in cybersecurity requires considering the linkages between cybersecurity frameworks and gender equality frameworks. Understanding how gender structurally operates within cybersecurity spaces is a crucial step in achieving a healthy system of cybersecurity. UNIDIR proposes a framework based on the design, defense, and response of cybersecurity activities so as to better identify how such gendered practices are part of the normative structure of this space, and to implement systems to mitigate gender inequality.

This reinforces the view that addressing cybersecurity and cybercrime from the points of view of communities most affected by power imbalances is critical for human rights, as well as for achieving success.

Conclusion

The prevention of cybercrime and improvement of cybersecurity are both worthwhile efforts that deserve attention and the further development of expertise. But solving each will by definition be different, and an approach that is functional in one area may not be functional in the other without serious adaptation and rethinking.

Today, cybersecurity and cybercrime policy practitioners are often asked to “stretch” between both domains. This poses risks, as these disparate approaches may not cleanly translate from one domain to the other. Taking into account these five myths will help us understand where a solution may be the right fit for one, but not the other.

To address this disparity, we recommend:

- All stakeholders shouldput the principles of safety, human rights and frameworks front and centerwhen developing cybersecurity policy, and take a narrower lens when developing and advocating for cybercrime laws.

- States must avoid developing cybercrime laws that may negatively affect the work of cybersecurity defenders, by outlawing or criminalizing their defensive activities, even though they may look like what a cybercrime law typically outlaws. They should do so by inviting other stakeholders to their conversations and enable an ongoing learning activity between these communities.

- States should develop proactive contributions to solving cybersecurity with other stakeholder groups and push accountable frameworks.

- States should actively narrow the range of issues covered in cybercrime to comprise “major crimes” and entirely exclude content-layer discussions.

- States ought to identify rights-respecting frameworks for accessing data by Law Enforcement Agencies across borders given the necessary and proportionate principles.

- Corporations should invest in appropriate cybersecurity programs and policies to avoid some of the outcomes that may require law enforcement to react.

- Civil society needto participate, and where possible, invite themselves to both cybercrime and cybersecurity discussions; and educate themselves on the different approaches each field requires. They should start with these 5 myths and work their way into guidance as published by specialized organizations, such as those referenced above.

The concepts in this essay were developed throughout the 2022 intersessional work of the IGF. As a work in progress, it was reviewed by a global multistakeholder community and we want to thank all interested parties who read the early drafts and who provided feedback. And to all who contribute to the BPF on Cybersecurity, we are thankful for their expertise and experiences around approaches that worked, and those that did not. We are a multi-stakeholder group of cybersecurity experts that are taking an outcome (incident)-focused approach to identifying appropriate cybersecurity efforts and anyone with relevant expertise can join us.

- - -

The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Secretariat. The designations and terminology employed may not conform to United Nations practice and do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Organization.

Authors