More Questions Than Flags: Reality Check on DSA’s Trusted Flaggers

Ramsha Jahangir, Elodie Vialle, Dylan Moses / May 28, 2024This piece is part of a series of published to mark the first 100 days since the full implementation of Europe's Digital Services Act on February 17, 2024. You can read more items in the series here.

European flags in front of the Berlaymont building, headquarters of the European Commission in Brussels. Shutterstock

It’s been 100 days since the Digital Services Act (DSA) came into effect, and many of us are still wondering how the Trusted Flagger mechanism is taking shape, particularly for civil society organizations (CSOs) that could be potential applicants.

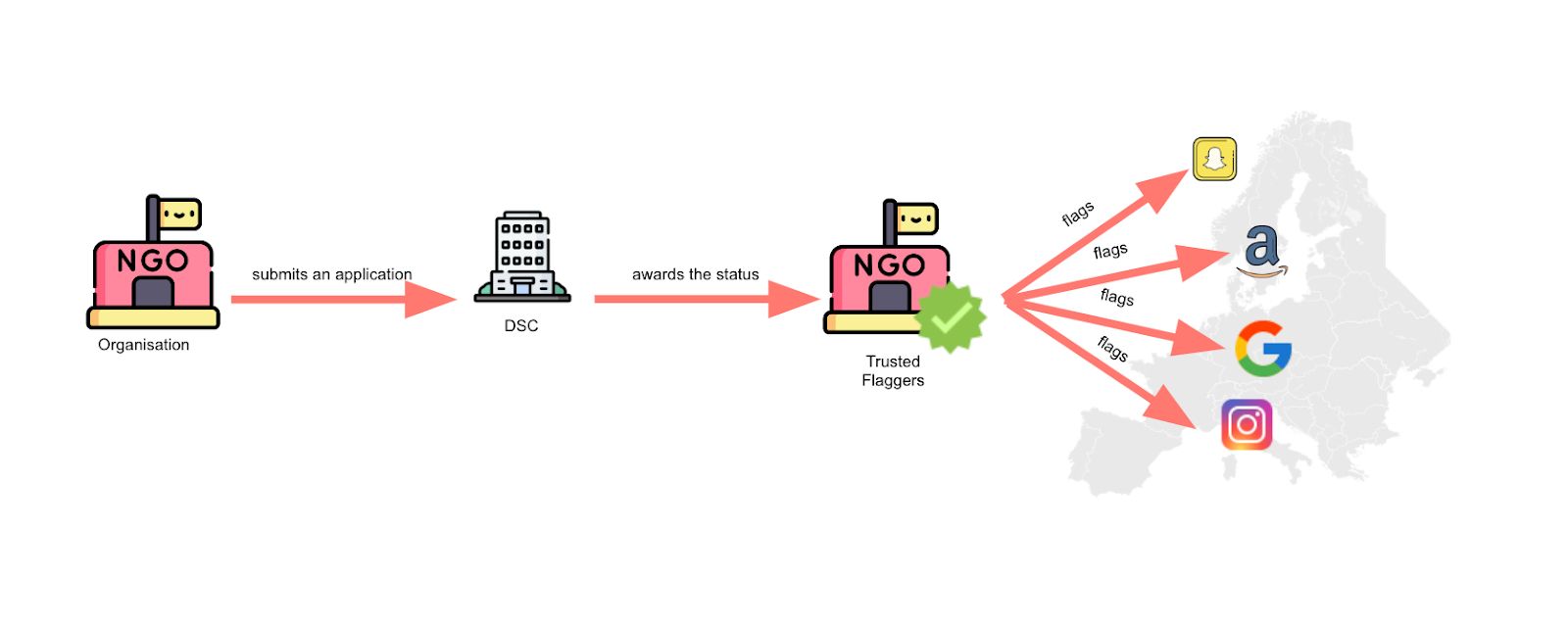

With an emphasis on accountability and transparency, the DSA requires national coordinators to appoint Trusted Flaggers, who are designated entities whose requests to flag illegal content must be prioritized. “Notices submitted by Trusted Flaggers acting within their designated area of expertise . . . are given priority and are processed and decided upon without undue delay,” according to the DSA. Trusted flaggers can include non-governmental organizations, industry associations, private or semi-public bodies, and law enforcement agencies. For instance, a private company that focuses on finding CSAM or terrorist-type content, or tracking groups that traffic in that content, could be eligible for Trusted Flagger status under the DSA. To be appointed, entities need to meet certain criteria, including being independent, accurate, and objective.

Trusted escalation channels are a key mechanism for civil society organizations (CSOs) supporting vulnerable users, such as human rights defenders and journalists targeted by online attacks on social media, particularly in electoral contexts. However, existing channels could be much more efficient. The DSA is a unique opportunity to redesign these mechanisms for reporting illegal or harmful content at scale. They need to be rethought for CSOs that hope to become Trusted Flaggers. Platforms often require, for instance, content to be translated into English and context to be understood by English-speaking audiences (due mainly to the fact that the key decision-makers are based in the US), which creates an added burden for CSOs that are resource-strapped. The lack of transparency in the reporting process can be distressing for the victims for whom those CSOs advocate. The lack of timely response can lead to dramatic consequences for human rights defenders and information integrity. Several CSOs we spoke with were not even aware of these escalation channels – and platforms are not incentivized to promote mechanisms given the inability to vet, prioritize and resolve all potential issues sent to them.

The formalized trusted flagging mechanism under the DSA is aimed at addressing this issue. As Trust and Safety practitioners, we are closely following the implementation of Article 22 on Trusted Flaggers, particularly through civil society engagements, such as the DSA Coalition for Civil Society Organizations led by the Center for Democracy and Technology, engagements with EU policymakers and regulators, as well as relevant partners in the Global Majority to discuss the implementation of the Trusted Flagger infrastructure under the DSA.

Trusted Partners process. Courtesy of ARCOM. ARCOM is the French Digital Services Coordinator. It facilitates the working group of EU DSCs implementing the Trusted Flaggers mechanism.

While member states are still appointing their Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs), significant questions linger regarding the vetting process for Trusted Flagger applications, regulator accountability, reporting methods, and, most crucially, how the system addresses the needs and resource limitations of civil society.

Accountability and risks associated with Trusted Flagger status

There are considerable risks in both the vetting process and risks associated with the Trusted Flagger status for civil society. According to Article 22 of the DSA, Trusted Flaggers need to demonstrate they operate independently from online platforms, and maintain transparent funding. But what does that really mean? In its current form, the Article could allow organizations that operate independently from platform companies to apply for Trusted Flagger status that may be directly or indirectly funded by social media platforms themselves in some way, creating a potential conflict of interest. There is a need to clarify this point in the process and be more prescriptive about what independence actually looks like.

Further, there is no clarity on how DSCs will address risks of government overreach and accountability. This is especially concerning in countries within Europe where CSOs have low trust in regulators due to a lack of transparency around their use of power and a history of overreach. It’s also worth noting that DSCs hold the power to revoke an entity’s Trusted Flagger status, a power which could be misused to censor independent organizations. Given the potential for overreach is high and the power DSCs have is quite substantial, their roles should be outlined in greater detail through consultations with CSOs.

There are also implications to consider for Trusted Flaggers operating in jurisdictions without adequate human rights protections or independent institutions, in the EU or if duplicated beyond in less democratic contexts. EU regulators will publish a public database of Trusted Flagger organizations. While transparency regarding state actors and law enforcement with Trusted Flagger status is valuable, the need for disclosure of information about CSOs requires careful consideration in contexts where they can be threatened for their activity or identity. Without caution and significant refinement, this has the potential to set a dangerous precedent, putting these stakeholders in direct jeopardy with their adversaries and significantly undermining existing trust and safety efforts to keep platform users safe and protect information integrity online. For instance, LGBTI helplines reporting discriminatory hate speech could be targeted. On the flip side, we should also be concerned about mal-intentioned Trusted Flaggers who might seek to report content they deem socially undesirable in an effort to remove that speech.

The implications of the EU shifting the power to designate Trusted Flaggers from companies to national authorities are global. At a time when civil society is facing heightened scrutiny over funding through foreign agent laws, disclosing funding to regulators could raise additional concerns – especially in authoritarian environments.

Standardized, tailorable reporting and communication channels between Trusted Flaggers, DSCs & platforms

Input from CSOs suggests platforms and DSCs have proposed varying reporting methods across member states. But currently, there is no standardized way to do this for Trusted Flaggers, and it will disproportionately impact under-resourced CSOs. Today, most CSOs reporting content to the platforms use encrypted messaging platforms, such as Whatsapp, Signal, or Proton. Since DSA, platforms require Trusted Flaggers to report content over email, while in other member states they recommend using a dashboard to flag content. Additionally, transitioning from emails and other ad-hoc processes to more formal, standardized channels will likely involve developing processes that require data sharing and custom tools - time and dedication that may be outside of the resource capabilities of many CSOs.

There is also a need to standardize the way Trusted Flaggers report to regulators. Trusted Flaggers are required to submit an annual report listing the number of notices categorized by: (a) the identity of the provider of hosting services; (b) the type of allegedly illegal content notified; and (c) the action taken by the provider. Trusted flaggers should send those reports to the awarding DSC and make them publicly available. The challenge is how they should document this without standardized reporting flows. Should they prioritize granular reporting such as statistics or share examples of content flagged via private escalation channels? Should there be a standardized reporting template? Either way, this level of compliance adds further burdens on organizations that may be viable Trusted Flaggers otherwise. To ensure consistency and clarity in reporting, platforms and DSCs need to consider standardized mechanisms that are tailored to the community’s capacity and needs.

The limited and dubious scope of “illegal” content

Under the DSA, Trusted Flaggers can report illegal content, not merely content that is harmful. Illegal content is defined either by EU or national legislation. According to Finland’s Traficom (the only DSC to have officially selected a Trusted Flagger so far), illustrative examples include “the sharing of images depicting the sexual abuse of children, the illegal sharing of private images without permission, the sale of non-compliant or fake products, the sale of products or the provision of services that violate consumer protection legislation, the unauthorized use of copyrighted material, the illegal provision of accommodation services or the illegal sale of live animals.” Ireland’s DSC, Coimisiún na Meán (CNaM), posted a non-exhaustive list of 60 categories of potential illegal content, including doxxing, for instance, which is one of the biggest threats for journalists and other targets of online abuse.

While indicative, the list does not comprehensively capture the full diversity of legal definitions across the 27 EU Member States or the diverse ways in which covered services may define prohibited content in their Terms of Service (ToS). The general lack of standardization for DSCs and platforms in terms of defining illegal content makes it difficult for interested organizations to understand what content can be flagged under the DSA.

Additionally, CSOs acting as Trusted Flaggers for platforms need to provide certain criteria or evidence when they need to escalate cases. In many contexts, there is a need to explain why a death threat is a death threat, for instance, or if they are truly at the whims of an authoritarian government. And that makes sense, since the platforms aren’t currently configured in such a way that they can reasonably devote emergency resources to every situation, and so they need to prioritize which cases get special attention. However, there is room for further guidance on what qualifies as illegal content under the DSA and what the sufficient level of evidence should be to submit notices to the platforms on what they must take action on– especially because interested applicants are required to demonstrate a record of successful flags to prove credibility and competence in their application for Trusted Flagger status.

Overlap with other content escalation partnerships

It’s also worth considering how the mandatory flagging mechanism under DSA overlaps with pre-existing escalation partnerships. The Trusted Flagger provision of the DSA is a way of creating formal regulatory oversight of a process that has been largely run by platform companies. Helplines from the INHOPE network, working on child protection, have been mentioned as examples of Trusted Flaggers, as it will enhance a mechanism they put in place already. How the Trusted Flaggers mechanism overlaps with pre-existing mechanisms, such as Trusted Partners programs, raises several questions:

- Will it be an opportunity for CSOs who desperately need more alert systems with social media platforms to get access to them and streamline processes?

- There is a lot of uncertainty about the fact that platforms could prioritize EU organizations over others, particularly those from the global south. Will other programs suffer from a prioritization of observing EU DSA compliance and therefore prioritization of the Trusted Flagger mechanism?

- There is also a need to further understand how this regulation will overlap with other digital regulations and guidelines – the EU AI Act, European Media Freedom Act (for media), various US regulations, and recent US Guidance for Online Platforms on ProtectingProtect Human Rights Defenders Online.

CSOs are under-resourced and are struggling to keep up

Finally, several barriers for organizations to apply for this status have been identified. For example, generally, CSOs are strapped for time and have limited means to complete all the application requirements currently asked of them. Large CSOs and private companies who would have the resources to comply with the DSA’s Trusted Flagger requirements may not be representative of all of the voices in civil society, or at least the ones who need to be elevated during times of crisis, and may have problems with truly being independent organizations if they have existing relationships with platform companies.

The EU Commission and regulators need to acknowledge this resource imbalance between the under-resourced CSOs and larger entities. There is a need a) to proactively engage with these CSOs to understand their incentives and inability to meaningfully engage with social media platforms and b) to create a simplified process with appropriate feedback loops to monitor the status of the case relationship. What is at stake is the legitimacy of the process, and regulators need to ask the question: who is the Trusted Flagger program for? Simpler onboarding and compliance mechanisms should be co-created with regulators and CSOs to better support the under-resourced CSOs that are applying for the status.

The EU Commission and regulators rely heavily on CSOs to ensure platform accountability and provide concrete support for the DSA's effective execution. The next 100 days should be a critical period for the Commission and regulators to prioritize facilitating CSO engagement, especially for under-resourced organizations supporting vulnerable users. A key aspect to address is developing standardized mechanisms that can be tailored for different Trusted Flagger categories.

To become a Trusted Flagger:

- You can reach out to the DSC of your country to get more guidance (Check if the DSC of your country has been appointed)

- Apply and make sure you comply with the criteria listed in this report.

Authors