Misinformation & mistrust thwarted COVID-19 exposure notification apps, GAO says

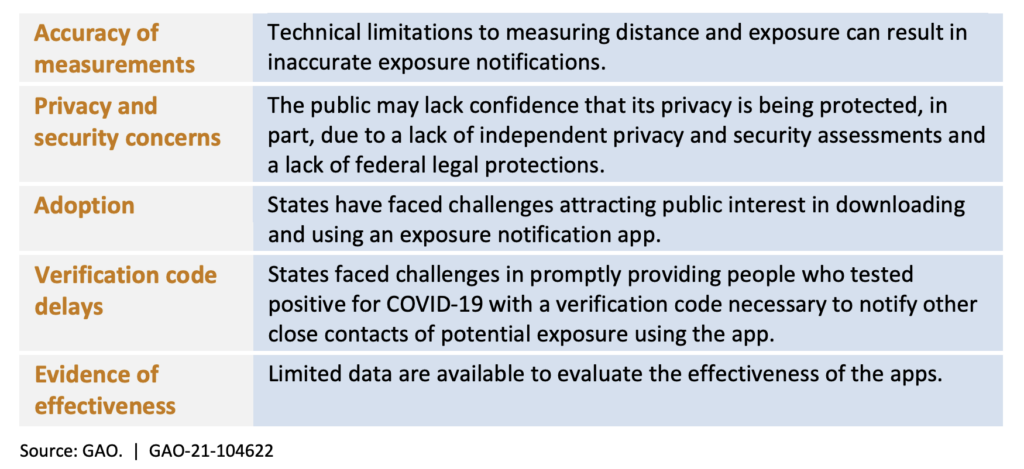

Justin Hendrix / Sep 14, 2021The Government Accountability Office (GAO), the non-partisan agency that provides facts and information to Congress and federal agencies, has released a report on exposure notification apps that looks at their deployment, benefits, challenges, and policies related to their use in an effort to determine best practices. It finds that adoption is hindered by "mistrust of governmental health authorities and technology companies," "misinformation about how the apps work and the data they collect," "lack of awareness of the availability of the apps," and "lack of necessary supporting infrastructure or internet service", in particular in rural places.

The government's inquiry follows the participation of various agencies in the funding, development and release of the apps and the protocols they employ, including the CDC, Department of Homeland Security (DHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and variety of other stakeholders, such as the Association of Public Health Laboratories. The private sector collaborated on the program extensively, including Google and Apple, makers of operating systems for most smartphones, as well as Microsoft and the not-for-profit MITRE Corporation.

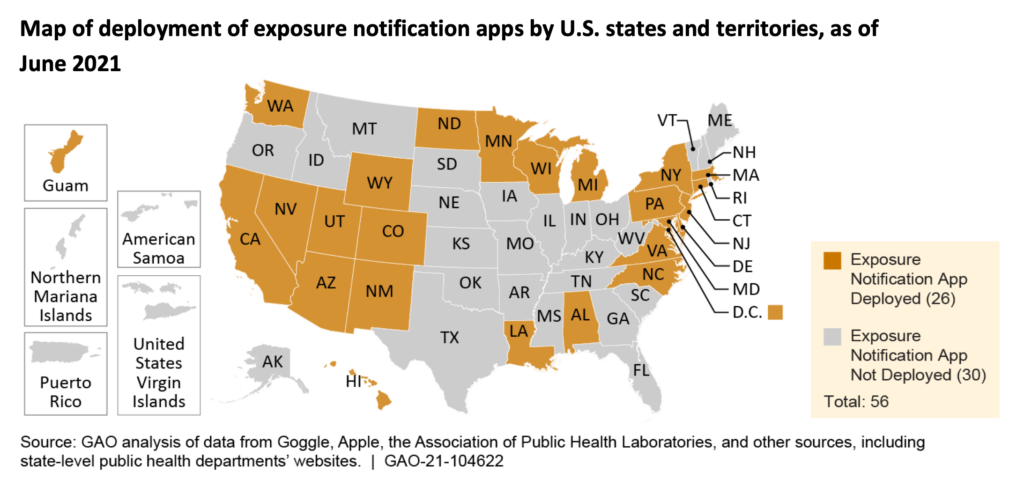

The report finds that through June 2021, 26 U.S. states, territories and the District of Columbia deployed an app to notify people who were approximate to others who tested positive for COVID-19. All 26 utilized the system developed by Google and Apple to enable a Bluetooth-based contact tracing platform compatible across iOS and Android devices. GAO interviewed state public health officials in nine states across the country that did deploy notification apps and received written information from two others, and it interviewed officials from seven states that had not deployed an app by the time of its review.

While the underlying technology was the same across the states and territories, each had to develop its own application. An "express" option was available for states and territories that sought to roll the app out quickly with standard functionality, while a "custom" option was available to states that sought to "to tailer the functions and features of their app" to provide additional services, such as helping to locate testing facilities or provide analytics on the spread of COVID-19 in the user's location. States reported variable costs to develop the apps and to market them. One state reported its development costs were $700,000. Marketing costs ranged in states that provided information-- from $380,000 to $3.2 million through June 2021, with many states using federal CARES Act funding to support development and marketing costs, in addition to their own funds.

How many people downloaded the apps? GAO notes that of the eleven states it surveyed, "four states reported less than 1 million, four states reported 1 to 2 million, and two states reported more than 2 million downloads (or activations), as of June 2021," while one state did not track data on the number of downloads. For two states, the number of users that received exposure notifications through June 2021 was 31,000 and 42,000, respectively. Four other states reported notifications ranging from 900 to 3,800, while the other states surveyed did not track these data.

The GAO reports only "limited data" are available on whether exposure notifications did anything to affect people's behavior. "Seven of the nine selected states that we interviewed said that they did not track whether app users actually sought testing or medical care based on the receipt of an exposure notification from an app; one state said it was done inconsistently and the other remaining state did not respond to our request for these data," says the report.

Noting that "there is no federal law that provides the public with clearly applicable privacy protections for the information that exposure notification apps gather," the report suggests the public may "lack confidence" in the apps. But privacy concerns may pale in comparison to other concerns- such as a lack of trust in government health authorities and tech firms, misinformation about how the apps work, and limited internet access in some regions.

The report does not note that when Apple and Google announced their partnership, then President Donald Trump immediately raised privacy concerns.

"It's very interesting, but a lot of people worry about it in terms of a person’s freedom," Trump told reporters at a White House briefing in April 2020, according to Politico, potentially deterring his supporters from using the apps before they were launched. "We're going to take a look at that, a very strong look at it." Ironically, researchers would later note his 2020 campaign app was a "surveillance tool of extraordinary power."

While some modeling evidence suggests the exposure notification apps may be somewhat useful in addressing disease spread, the evidence is limited and research results are still pending. "Exposure notification apps are a relatively recent public health intervention," says the report. "As a result, additional primary research on the benefits and effectiveness of exposure notification apps is needed, according to CDC and other public health researchers."

In order to improve future use of exposure notification apps, GAO suggests more research and development "to address technological limitations"; efforts to address privacy and security, including uniform standards; implementing better measures of effectiveness, and a more coherent national strategy. But, without national privacy legislation, a national tracking app may not fly. "Due to the absence of a federal privacy law in the U.S., the public may be less likely to trust the federal government’s privacy protections."

Authors