Mis- and Disinformation Creates Additional Barriers for Women of Color Politicians in the U.S.

Dhanaraj Thakur, DeVan Hankerson Madrigal / Nov 3, 2022Dhanaraj Thakur is Research Director at the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) and DeVan Hankerson Madrigal is CDT’s Research Manager.

This essay is part of a series on Race, Ethnicity, Technology and Elections supported by the Jones Family Foundation. Views expressed here are those of the authors.

As recently as a month ago, political ads posted on Twitter used misinforming, identity-based targeting in order to sway voters against Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, a woman of color. These ads, which promote false information by artificially darkening Abrams’ complexion, were flagged by users on the platform (as well as in the press) for playing into white racial anxieties.

While mis- and disinformation is a major concern for policymakers, this example points to a gap in policy discussions, particularly in the U.S.: the problem is both racialized and gendered. This came to the fore in the 2016 and subsequent U.S. elections where researchers identified voter suppression disinformation campaigns targeted at communities of color, and women in particular. As the 2022 midterm elections draw to a close and yet another Presidential cycle looms, it is urgent that this issue is given consideration, and that efforts to mitigate it are implemented.

Of course, mis- and disinformation targeted at communities of color is not new. Black media outlets, for example, have had to counter false narratives from various sources for a long time. In 1909, the Baltimore Afro-Americanpublished an editorial challenging the disinformation being shared by another newspaper which claimed that the "grandfather clause" (i.e., requiring that, in order to vote, a person's grandfather should have voted by 1869) was not meant to disenfranchise African-American voters.

Today more researchers (especially those from communities of color) are identifying and analyzing evidence of how online mis- and disinformation is targeted at communities of color in specific sectors such as health or elections, or the ways disinformation campaigns antagonize relations between communities of color. That said, important gaps still remain, including approaching the problem from an intersectional perspective that considers gender, race, and other identities. For example, political candidates including women are more often the subject of mis- and disinformation than men. However, few examples of research examine this phenomenon from an intersectional perspective. One study looked at Kamala Harris' campaign in 2020 and found that she was the subject of four times as much misinformation when compared to white men in similar campaigns. Another study that similarly looked at women candidates of color (specifically some members of the "Squad," including Reps. Ilhan Omar (D-MN), and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY)) also found a disproportionate impact.

However, none of these studies took a representative look at all candidates that ran in a national election to see if this problem extended to women of color candidates in general (and not just a well-known few). Such systematic targeting of women of color is important to study because this group already faces significant barriers to entry into representative politics. Only 10% of candidates that ran in 2020 were women of color, according to the Reflective Democracy Campaign, and this lack of representation in Congress undermines the quality of our democracy. Thus, understanding the extent to which women of color are subject to mis- and disinformation online and the kinds of impacts this can have on them is crucial. This is part of what our new study addresses.

For our report, titled An Unrepresentative Democracy: How Disinformation and Online Abuse Hinder Women of Color Political Candidates in the United States, we reviewed over 100,000 tweets that were targeted at or were about a representative sample of the approximately ~1100 candidates who ran for Congress in 2020. We then assessed the extent to which these tweets contained mis- and disinformation about the candidates themselves, something they said, or other related issues. We also examined the tweets to see whether they contained abuse such as the use of offensive language, threats of violence, misogyny, racism, doxxing, etc.

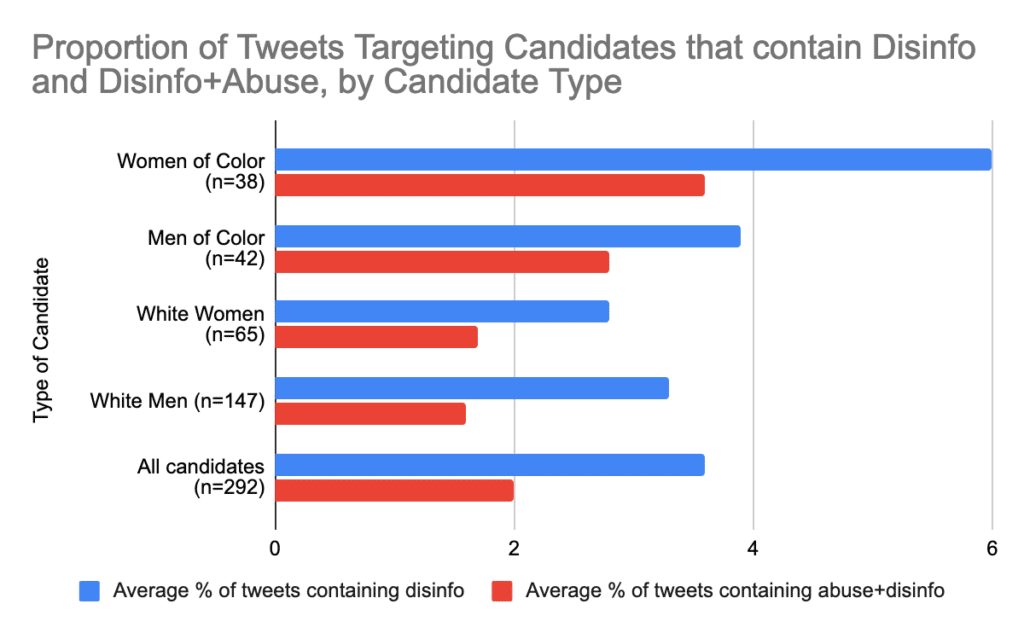

While the full report includes several findings, we highlight three here about the problem of mis- and disinformation. First, we found that women of color political candidates were almost twice as likely as other candidates (i.e., men of color, white women, and white men) to be targeted with or to be the subject of mis- and disinformation. In some instances, posts with mis- and disinformation were related to the election (with false narratives about illegally obtaining votes or the inaccuracy of mail-in ballots, as noted in Figure 1) or COVID-19 (with false narratives about vaccines or wearing masks).

A second finding is that women of color political candidates were twice as likely as white candidates to be targeted with or be the subject of tweets that contained both mis- and disinformation and abuse. The combination of mis- and disinformation and abuse undermines the political effectiveness of women of color candidates and controls how the public views them. This is part of the larger problem of violence against women politicians and more specifically the misogyny and racism that women of color in particular, such as women of African descent, face online.

Both of these findings are summarized in Figure 2, which also shows how women of color political candidates were on average more likely to be targeted with or be the subject of tweets that contained mis- and disinformation and both mis- and disinformation and abuse than all candidates.

A third finding related to the main narrative of the tweet - e.g., was it about the candidate's policy positions, their character, ideology, or identity. We found that women of color were twice as likely as other candidates to be targeted with or to be the subject of posts focused on identity. More specifically, such posts often focused on the candidate's gender or race. This was particularly pronounced for women of African descent or African American women.

In order to better understand this pattern we also looked at gender and race in combination. We examined whether people maintained a combined focus on gender and race in these instances. What we found was whenever identity was the main focus of a tweet at or about them, women of color were six times more likely to encounter tweets invoking both their gender and race compared to other candidates. This is in contrast to the likelihood of posts focused on policy, ideology, etc. which were relatively similar across candidate groups.

Given these problematic trends, we interviewed women of color political candidates that ran for Congress in 2020. We asked what kinds of impacts these attacks of mis- and disinformation and abuse had on them and their campaigns. Based on their experiences using multiple social media platforms for their campaigns, they reflected on three key points:

- First, they felt that the aim of the people behind these attacks was to make the candidates accept the oppression they face as women of color and drop out of their races.

- Second, the attacks focused on the fact that the candidates identified as women, as well as the candidates’ other identities or attributes, such as their age, race, marital and parental status. This was corroborated by our analysis of Twitter data, which showed that women of color were more likely than other groups to be targeted with or the subject of posts that focused on attributes of the candidate’s identity such as gender and race.

- Third, although many of the attacks were severe, candidates together with their campaign teams displayed a significant degree of resolve, resilience and coping skills. In most instances, study participants finished out their races and several remain in politics in some capacity.

That said, the candidates' insights and our data analysis suggest that much more work needs to be done. Social media platforms should build upon their existing policies that prohibit harassing or abusive content by publicly providing information about how they consider gender and race in their policies and enforcement processes against mis- and disinformation and abuse. Companies should also generally make more data available to independent researchers to enable them to study the impact of mis- and disinformation and online abuse, including gender based violence (GBV), on political candidates. And, companies must conduct risk assessments of their ranking and recommendation systems to evaluate their impact on women of color candidates and what abuse mitigation measures the service provider can implement.

But social media companies are not the only ones who can take constructive action. Political parties and other organizations that work with campaigns should better support women of color candidates through, for example, training to manage and address mis- and disinformation and abuse online, and toolkits to improve the digital security of candidates and their campaigns. Researchers that focus on mis- and disinformation should invest more in research that includes questions on intersectionality, including on gender and race. Our study is one of too few attempts to do this. Ultimately, we all have a significant role to play in addressing the problems that women of color political candidates face online today.

The status quo is unacceptable if we are to have a truly representative democracy.

Authors