Jan 18, 2012: The Day When Tech Changed Politics for Good

Micah Sifry / Jan 18, 2022The anti-SOPA-PIPA fight galvanized millions and flipped Congress on its back. Ten years later, what are the lessons to be learned?

Micah Sifry is the publisher of The Connector, a newsletter focused on news and analysis at the intersection of politics, movements, organizing and tech, where this reflection was originally published.

If you were forced to pick one day when America’s political establishment finally realized that the Internet had changed the rules of politics, what would it be? February 1, 2000—when presidential candidate John McCain raised $1 million online in the 48 hours after his upset win in the New Hampshire presidential primary? December 20, 2002--when Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott resigned his leadership in response to pressure from political bloggers who had unearthed damning evidence of his support for white segregationist Strom Thurmond? August 11, 2006—when Republican Governor George Allen’s “macaca moment” was captured on videotape, fatally wounding his re-election campaign? Or December 16, 2007, when Republican presidential candidate raised a whopping $6 million “money bomb” for his campaign in one day?

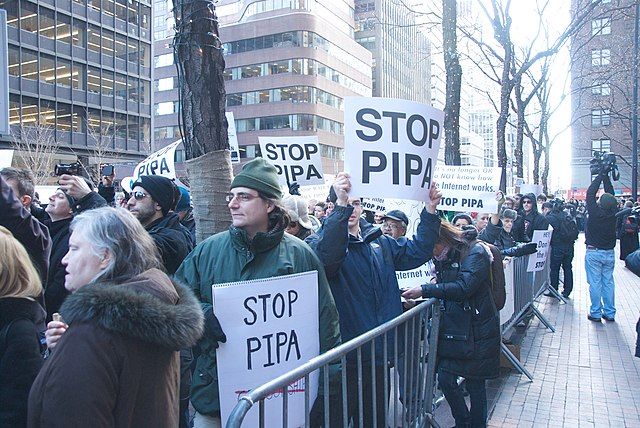

While all of those events contributed to a growing sense that the open Internet was changing politics, in my humble opinion they all pale next to January 18th, 2012, when more than 115,000 websites went dark or altered their home pages to drive their users’ attention to Congress, galvanizing massive opposition to two dangerous pieces of legislation, the Stop Online Privacy Act (SOPA) and the Protect IP Act (PIPA), which would have enabled the government to shut down sites that allegedly violated copyright. An estimated ten to fifteen million people expressed their opposition directly: Congress’ phone lines, fax lines and in boxes were all flooded. A million people signed a petition organized against the bills organized by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Another 4.5 million signed a petition on Google’s home page. In New York City, two thousand techies took off their lunch hour to rally outside the offices of Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand. Sponsors of the two bills, which was heavily backed by Hollywood and other copyright-centric industries, began visibly flipping their positions. Two days later, the bills were withdrawn from consideration. Below is a visualization showing how quickly the tables turned, made by Dan Nguyen, a developer at ProPublica whose “SOPA Opera” site tracked lawmakers’ positions.

The SOPA-PIPA “blackout day” and victory was a high-water mark for everyone who saw the open web as a new platform for public participation that could shift power into many more hands. Yochai Benkler, a professor at Harvard Law School, wrote a powerful analysis a year later (with a group of collaborators) that showed, in glorious detail, how a widely distributed network of organizations and media sites had galvanized attention to the two bills. The image below shows the week of the blackout, when over 3,000 stories appeared. Techdirt, CNET, Ars Technica; Wikipedia; the EFF; OpenCongress and Fight for the Future—all key nodes in the organizing push—are prominent.

After the SOPA-PIPA victory, people debated what it meant. Some saw proof that Google and Facebook had finally flexed their latent political muscle. While this was true, Big Tech rarely uses its platform power to mobilize individuals the way it did around SOPA-PIPA, preferring instead of hire armies of traditional lobbyists. Others pointed, with justification I believe, at how a small collection of internet rights organizers and tech media had, through hard work, built a growing network of activists, then managing to leverage online communities at hubs like Wikipedia and Reddit along with public-spirited tech leaders at companies like Tumblr, which first blacked out its site the prior November. The coalition spanned the political spectrum, pulling in rightwing sites like RedState and Drudge Report alongside left-leaning hubs like DailyKos and Demand Progress, along with pop figures like Justin Bieber. It helped also that the anti-SOPA-PIPA coalition had a simple and compelling message: to stop censorship of the Internet.

Then What Happened?

The American Internet has never had another day like January 18, 2012, and it’s worth pondering why. We’ve certainly had a few galvanizing moments that could have had a similar rallying effect. One came June 6, 2013, when Glenn Greenwald reported for the Guardian that the National Security Agency was secretly collecting the telephone records of millions of Americans and had obtained direct access to Google, Facebook, Apple and other big platforms, the first of many revelations from Edward Snowden. Another came March 17, 2018, when the New York Times and the Guardian jointly reported that Cambridge Analytica, a UK-based voter profiling company, had harvested the private information of more than 50 million Facebook users in America, using it to help the Trump campaign target voters in 2016.

Both of these scandals generated tremendous public attention and activism. I remember sitting on the floor of a conference room at Personal Democracy Forum in New York with several organizers the night of June 6, 2013, including leaders of EFF, Demand Progress, Free Press, Mozilla, and Fight for the Future, as they strategized and quickly built a joint website called “StopWatching.us” in response to the NSA’s surveillance programs. And Cambridge Analytica was arguably the moment when many people realized how much their personal data had been commoditized. Now many new organizations are engaged in fighting “surveillance capitalism,” like the Algorithmic Justice League, the AI Now Institute, the Data & Society Institute and the Athena coalition.

Still, I’ve sometimes wondered why the millions of people who expressed their opposition to SOPA-PIPA so effectively were never organized into an ongoing movement at anything like that scale. Arguably, the closest we came to converting the “no” energy of that fight into “yes” energy was the push throughout the 2010s to defend net neutrality. In 2017, more than 22 million public comments were filed with the Federal Communications Commission regarding its planned repeal of net neutrality protections, but later investigations found that nearly 80% of those were fake, submitted through a secret campaign funded by the broadband industry. During an earlier comment period in 2014, about four million people spoke up about the rules. Somewhere between the SOPA-PIPA fight and more recent ones, millions of people dropped out of participating.

I asked a few key participant-observers for their thoughts on what happened, and why the anti-SOPA-PIPA movement was so much bigger than more recent ones focusing on either government or Big Tech surveillance. One thing I was curious about was whether the internet freedom world was naïve about Big Tech, or if organizations got co-opted or tilted their focus based on funding opportunities. Google in particular was a very energetic funder of many groups in those years, and a number of big foundations also invested in supporting groups working on issues like net neutrality.

Ethan Zuckerman, who spent most of the period in question at MIT running the Center for Civic Media and now teaches at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, had a few hypotheses. First, that the SOPA-PIPA bills were obviously out of proportion to the “crime” they were supposed to be addressing: nearly everyone could agree that shutting whole websites down if one piece of content violated someone’s copyright was an overreach. Second, that “activism focused on passing or not passing laws may be easier than activism focused on companies that most of us use every day.” Ethan added, “I can decry Google's role in normalizing surveillance capitalism, but I still use their main product because it's better and more versatile than DuckDuckGo.” His third theory was even more shrewd: we don’t care enough about online privacy because we like “free” services. He told me, “fighting surveillance capitalism would mean we would need to actively start paying for the services we use. The mistake we may have made, many years ago, was setting the norm that services online were free and never accustoming people to a switch, like the switch into paid programming made by Netflix and others.”

He also added, “I am increasingly amazed at our collective inability to imagine futures beyond capitalism. I started thinking this through as I am watching the people I want to be thinking about the future of the internet move towards web3 as a paradigm for the way forward. Zizek (and others) have observed that it's easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism: to me, web3 reflects an inability to imagine voluntary collective goods existing at scale (ignoring Wikipedia as the obvious example) or state-created public goods (ignoring most of Europe as well as critical pieces of US infrastructure), and an assumption that markets are necessary to solve all problems. Maybe that's why movements against Facebook et al ultimately fail - we can imagine not passing a bad piece of law, but we cannot imagine the death of for-profit companies that cause social harm. It's easier to imagine one form of change over another and therefore the change is easier to accomplish.”

Holmes Wilson and Tiffiniy Cheng, two of the original founders of Fight for the Future, were kind enough to give my questions a lot of thought (even though they have moved onto other endeavors). For starters, Holmes said that the issues weren’t similar. “Privacy was always much harder to get people engaged with than SOPA or Net Neutrality, even after the Snowden revelations,” he told me. “It was important to us, and we spent a ton of time building campaigns around it, including on a pre-Snowden anti-NSA surveillance campaign that visually and emotionally was some of our best work. But you always felt a huge headwind against the general feeling that there was so little anyone could do, and against the narrative in Hollywood movies that it was normal or legitimate (if a bit creepy) for governments to be omnipotent digital spies.”

He also agreed that some people in the broad advocacy movement around online privacy sold out, going to work for companies like Facebook. And, he added, “Google did have a degree of influence over the NGO community due to its grantmaking and presence overall, and if it was Google in the crosshairs in 2017 and not Facebook, I think you might have a hard-to-refute case that some of the difference between post-Snowden and post-Cambridge Analytica was due to inappropriate coziness.”

But he thought more attention got focused on government surveillance than surveillance capitalism because the issue was genuinely bigger. “China uses surveillance to put people in concentration camps. Russia uses it to poison activists like us. The U.S. uses it to kill both targets and bystanders in thousands of drone attacks. Facebook uses it to... get you to use Facebook more, or buy some dumb shit you don't need?” As a private company, Facebook may someday be gone, but the NSA and the GCHQ will still be around. He has a point, several of them.

He and Tiffiniy also both argued that organizing the millions of people who came out against SOPA-PIPA into some kind of local, decentralized network of “internet rights” activists (like the National Rifle Association, say) was a much heavier lift than anyone was in a position to do. “I wonder if Internet rights clubs could really exist,” Tiffiniy told me. “We sort of tried that after SOPA but weren’t solely focused on it so moved on.”

Holmes said, “As far as organizing people after SOPA goes, I think that could have been an awesome project, but it also could have been a lot of work and a bit like pulling teeth. We set something up called the Internet Defense League, online, but it was difficult because subsequent threats were often very different from SOPA and required a fresh explanation and a different coalition. In-person organizing can be amazing but it's also very costly in terms of time for the participants, and I'm not sure we had ways to organize them effectively enough to make their time count. People are really legitimately busy with their lives. And after all, there are other important issues in the world beyond the Internet and technology policy, right? Sometimes it's good for other movements to grab the world's attention.”

Cory Doctorow, the science fiction author and longtime organizer with EFF, mirrored Holmes and Tiffiniy’s argument that government surveillance was a far more serious and galvanizing issue than the kind of private data-mining and abuse enabled by Facebook. So, why didn’t the anti-SOPA-PIPA movement do more post-2012 to push back on the rise of Big Tech? Cory had an eloquent and convincing answer, which is worth quoting at length:

“The tech rights world had a GIANT blind spot, but it wasn't about the much-vaunted, evidence-free proposition that machine learning and big data would deliver mind control rays to Big Tech (a myth that serves Big Tech with each repetition, bolstering its own self-serving boasts about the efficacy of online advertising).

Rather, our blind spot was monopoly, and the role monopoly played in distorting all forms of policy, including tech, copyright and privacy. The copyright wars of the mid-nineties to the early 2010s were an epiphenomenon of the entertainment industry's high degree of concentration. The small number of large firms dominating music, TV, broadcasting and film allowed for the extraction of monopoly rents and lowered the bar for collective action, allowing these oligopolies to convert monopoly rents into policy advocacy. That's where SOPA came from.

The tech sector of the day was disorganized, with many fast-growing, extremely competitive small and medium enterprises. The giants of the day were still fragile (Microsoft a convicted monopolist still bruised by the antitrust investigation; Apple just starting to consolidate its gains from the mid-2000s after its near-death experience, Yahoo creaking under pressures of holding together its idiotic portfolio of finance-driven acquisitions, etc). They sucked at lobbying, both because they were not yet in a position to extract monopoly rents from their customers and monopoly concessions from their workforce, and because a sector that large and disorganized couldn't arrive at a common lobbying position.

Today, entertainment is even MORE concentrated and tech has caught up - and it now equals or surpasses entertainment in lobbying. The YouTube of the SOPA era was reeling from Viacom's legal assault; the YouTube of today is cutting deals with Viacom and its co-oligopolists.

Tech once had its users' backs - not because of any special moral center, but because in a competitive market where services had low switching costs, your users' views of your conduct actually mattered to your bottom line.

That's clearly not the case today. Big Tech (irrespective of its posture on surveillance) has attained a status where it is literally illegal to help users escape its walled gardens (DMCA 1201, CFAA, tortious interference, etc), and where any firm that comes close will either get crushed (the "kill zone") or acquired (Instagram, Whatsapp, etc).

This concentration - what Tom Eastman calls the conversion of the Internet into "five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of text from the other four" - means that pro-user advocacy now fights on TWO fronts. When we fight the EU's TERREG or Copyright Directive, we're not just fighting spooks and Big Content, we're ALSO fighting Big Tech, who merrily sell us out. When we try to save CDA 230, we're not just fighting would-be censors, we're also fighting Facebook, who have found common cause with censors in demanding the elimination of safe harbors as a means of increasing the capital costs of competing with Facebook.

User advocacy is bigger than ever - it's just that the fights got harder. The petition against the EU Copyright Directive was the largest in EU history. Hundreds of thousands of people marched in 50 cities against it.

My hope today is on coalitions between digital rights movements and other anti-monopoly movements: the recognition that tech isn't exceptional, and the forces that drove its consolidation are identical to the forces that created monopolies in health and energy and finance and beer and entertainment.

As James Boyle has written, the term "ecology" was a watershed movement, connecting thousands of otherwise disjointed causes from owls to the ozone layer. Today it's easy to see ships stuck in the Suez Canal and pro wrestlers begging for medical help on Gofundme as separate issues, but they're both facets of the same problem, and it's the same problem plaguing Hollywood writers and performers as well as tech users and tech workers: monopoly.

The tech rights world didn't sound the alarm on monopoly early enough, but it's not too late. There are more allies in this fight than we can count. Corporate impunity and dysfunctional policy are the result of 40 years of official orthodoxy that treats monopoly as "efficient." That orthodoxy is crumbling now. We need to accelerate it - to save out tech infrastructure for human thriving, to save our food supply, to save our environment and planet.

Amen to that. As Cory says, the anti-SOPA-PIPA moment was a big one but it won’t be the last one. “The flashpoint might not be an internet regulation - it might be a voting regulation, or a protest regulation, or an abortion regulation - but it'll be fueled by the same outrage (and if it happens, it will be coordinated by the internet).”

Bonus link: Here’s a list of current and upcoming events focusing on SOPA-PIPA at ten years, courtesy Dee Harris of Creative Commons.

Authors