Internet Governance and Digital Governance: Are They the Same Thing?

Konstantinos Komaitis, Jordan Carter / Sep 13, 2023Konstantinos Komaitis and Jordan Carter reflect on the rise of global discussions about digital governance and seek to position it in relation to the more mature field of internet governance.

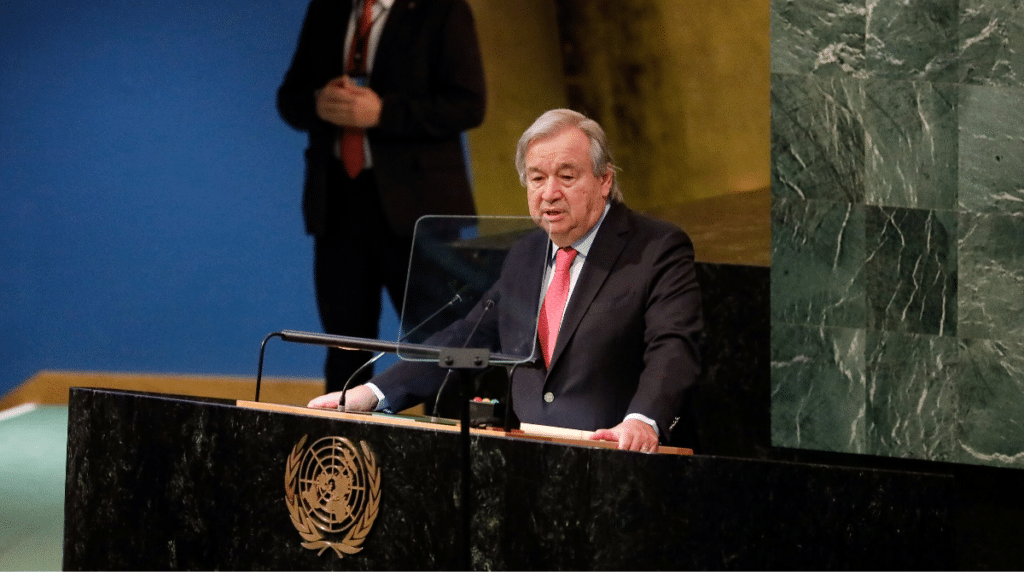

In May, the United Nations Secretary-General (SG), António Guterres, published a suite of policy briefs that share his vision on the topics being canvassed at next year’s Summit of the Future, including his thinking regarding the need for a Global Digital Compact (GDC).

In one of his briefs, entitled “A Global Digital Compact – An Open, Free and Secure Digital Future For All," SG Guterres “proposes the development of a Global Digital Compact that would set out principles, objectives, and actions for advancing an open, secure and human-centered digital future.” But it is his reference to “digital governance” that seems to position this document apart from the historical discussions around internet governance.

Scoping digital governance and framing it in relation to internet governance is a conversation that perhaps is overdue, given the increasing regulation related to digital issues that is taking place in jurisdictions around the world. As negotiations on the Global Digital Compact are due to begin, being clear about the current and desired linkages between the two fields will be important to avoid risks – one among them being the accidental dissolution of the internet governance system into the much broader concerns of digital governance.

It is unclear from the brief what the SG means by “digital governance,” though the term is used interchangeably with “internet governance.” However, its use throughout the brief raises the interesting point of whether it is helpful to start thinking explicitly about what it means and how it fits with the internet governance discourse.The reality is that the United Nations is seeking ways to engage in the digital realm but, in order to do so effectively, scoping “digital governance” will be key. We are not quite at the stage of whether ‘digital governance is governance,’ and, to this end, some conceptualization is required.

One characteristic that seems to fit digital governance is that the term is more appropriate when talking about specific issues relating to technologies, applications, and services that use the internet’s protocols and standards (i.e., its infrastructure), but are also distinct from it, i.e., artificial intelligence. With this in mind, we argue that digital governance points to issues that are more focused-oriented, affect the everyday online habits of users, and necessitate structures that consistently address these issues. It may, therefore, be helpful to think of the issues falling within the realm of digital governance similar to the way we think of public health: issues that affect a significant number of users, the level of severity that is significant, the mode of “transmission” usually involves one user passing down the issue to other users and, finally, the fact that they create the need for the activation of frameworks that ensure safety, quality control, and efficiency.

Thus, we argue that digital governance relates to regulatory initiatives that are addressed at a national level or though independent or self-regulatory initiatives, yet they can have an international impact. Examples could include the Digital Services Act (DSA) package or the AI Act in Europe; the provisions regarding Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the United States; Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code; or, Brazil’s Marco Civil. They could also include self-regulatory initiatives, including the Oversight Board, the Christchurch Call, the Trust and Safety Partnership (DTI), etc. This sounds more like digital governance.

On the other hand, internet governance “is the development and application by governments, the private sector, and civil society, in their respective roles, of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures, and programs that shape the evolution and use of the Internet.” This definition, developed by the Working Group on Internet Governance (WGIG), dates back to 2005 and has remained unchanged. It aims to reflect the absolute requirement for inclusion and participation as it relates to the governance of the protocols and standards that underpin the existence and future of the Internet. These have historically been developed and should remain under the purview of the multistakeholder model, driven by a combination of market dynamics, decentralized architectures, and the need to abide by a normative framework that has developed through the years of Internet governance and management.

Learning from internet governance to inform digital governance

When we reflect on the earlier need to develop internet governance frameworks some thirty years ago, we see some striking parallels. Then, as now, the geopolitical situation was in flux. Then, as now, there was a need to accommodate the rising new technologies in broader systems of governance, so they could be connected with broader social concerns, or they could simply be developed and expanded in a logical and sustainable way.

At the current moment, technologies are developing in leaps and bounds. States are racing to catch up, with diverse regulatory approaches emerging and consequential pleas for coherence and consistency. While the ongoing need for reliable, stable connections provided by the internet are almost simply infrastructure these days, the newer ‘digital techs’ in the headlines - from AI to platform regulation- are not, and they are perhaps crying out for new ways to understand and manage their impacts. In other words, the need for and the reality of digital governance are well in evidence—but broad-based frameworks are not.

In digital governance, the issues are newer and deeply philosophical questions about where the rights and interests of users sit are being debated. Governments have always had a key role in determining public interest in this, so it is no surprise that they are working through the familiar, state-based approaches of the UN, to better address them. This, of course, does not mean that input from other stakeholders should not be sought, but, at the end of the day, states are the legitimate agents when it comes to issues of public interest. It is partly for this reason that dealing with such issues is also often a regulatory task, at least in part - pointing further toward the need for an important role for nation-states.

While digital governance and internet governance are separate fields, they are, of course, related. Many new technologies at the heart of digital governance debates rely on the internet to exist or succeed. In turn, their development and needs should shape the evolution of the internet. Internet and digital governance are, therefore, distinct, but they are not siloed – they are consequential, and one informs the other. As a result, the summit of the future and the upcoming World Summit on Information Society (WSIS+20) review in 2025 provide a unique moment.

The main question is whether we could use this moment to:

- Strengthen the internet governance system, making it more inclusive and effective, and building new links and connections between it and nascent digital governance efforts.

- Apply some of the insights from thirty plus years of internet governance - not least the benefits of well-designed multi-stakeholder forums and institutions - to the development of digital governance.

- Develop a shared concept of the respective roles and responsibilities of the existing internet governance system and the nascent digital governance system.

The internet needs governance. So do broader digital technologies. Let’s make that happen in a way that keeps adequate attention on the internet’s growth and development, and builds the system we need to make newer digital technologies also serve the public interest.

Authors