India’s Draft Telecommunications Bill Fails to Democratize the Telecom Sector

Anushka Jain, Prateek Waghre / Nov 4, 2022Anushka Jain is the Policy Counsel and Prateek Waghre is the Policy Director at Internet Freedom Foundation, a New-Delhi based digital rights organization that seeks to ensure that Indian citizens can use the Internet with liberties guaranteed by the Constitution of India.

Today, telecommunications is the lifeblood of any economy, and in recent years telecommunications technology has developed at an unprecedented speed to respond to this need, particularly in India. As of 2022, mobile internet users in India consume among the highest volumes of mobile data per user at 17 GB/user. This is estimated to increase up to 50GB/user by 2027. In the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)’s ICT Price Baskets,India is in the top 10 most affordable countries for 4 of the 5 baskets. Since 2018, the percentage of people using the internet has more than doubled.

Despite this growth, the Indian telecommunications sector continues to be governed by laws promulgated in the 19th century. Growing calls for reform pushed the Government of India to declare its intention to bring the Indian telecommunications sector into the 21st century with new legislation.

The draft Indian Telecommunication Bill, 2022 (“Telecom Bill, 2022”) was released for public consultation by the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) under the Ministry of Communications on September 21, 2022. The 40-page bill was accompanied by a 19-page explanatory note. It consolidates the laws governing the provision, development, expansion & operation of telecom services, telecom networks & telecom infrastructure and assignment of spectrum in India. In doing so, it repeals the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act, 1933, & the Telegraph Wire (Unlawful Protection) Act,1950. On the other hand, any rules defined by these laws will continue to be in force. We’ve flagged several major issues with the Telecom Bill, 2022 in a public brief leading us to recommend its withdrawal. We discuss a few of these issues here.

A. Issues with consultation process

The Telecom Bill, 2022 purportedly takes into account the comments received from stakeholders & industry associations on the consultation paper on the “Need for a new legal framework governing Telecommunication in India” which was published on July 23, 2022. (Read IFF’s comments on the paper here). The deadline for submitting comments on the paper was August 25, 2022 which was further extended to September 1, 2022. The Telecom Bill, 2022 was released three weeks after this deadline. As per a response received under the Right to Information Act, 2005 (RTI Act), the DoT received approximately 500 pages worth of comments on the consultation paper. However, these responses have not been made publicly available, in a clear failure to comply with the Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy, 2014.

Further, the consultation paper also did not explicitly include either the reasoning or the indication for including substantive changes such as the expansion of the definition of “telecommunication services”. Since this proposed change is the most drastic and will have effects on multiple categories of players in the Indian telecom sector, this is a clear failure of the entire consultative process. The consultative process followed so far is not commensurate with the ambitious and vital goal to establish a modern legal framework for the telecom sector.

B. Expanded definitions clause

Presently, provisions of the existing acts such as the Telegraph Act, 1885, which were enacted before the advent of the modern communication technologies we use today, are being interpreted widely to regulate them. The Telecom Bill, 2022 through its expanded definitions clause makes specific reference to modern technologies, in an attempt to be comprehensive. Here, the definition of “telecommunication services”, as contained in Clause 2(21), has been expanded to include service of any description which is made available to users by telecommunication which includes broadcasting services, electronic mail (Gmail), voice (TSPs such as Vodafone), video communication services (Skype), fixed & mobile services (BSNL), internet & broadband services (Act Fibernet), satellite based communication services (Bharti Airtel), internet based communication services (Reliance Jio), in-flight & maritime connectivity services (Tatanet), and interpersonal communications services (WhatsApp, Signal).

In the absence of clear definitions, several service providers which deliver multiple functionalities may have to be dealt with on a case-to-case basis, potentially leading to ad hoc outcomes.

C. Increased regulatory burden and centralization

Clause 3(1) of the Telecom Bill, 2022 provides the Union Government with the exclusive privilege to provide telecommunication services, establish & operate telecommunication networks and infrastructure, and use and allocate spectrum. In exercise of this privilege, Clause 3(2) allows the Union Government to prescribe licenses for providing telecommunication services or establishing, operating, maintaining and expanding telecommunication networks. Clause 4(1) states that this privilege will be provided procedure through rules that the Union Government may prescribe at a later date for payment of entry fees, license fees, registration fees or any other fees or charges. Thus, each service included in the list of services in the expanded definition of “telecommunication services” will now have to obtain a specific license to operate in India. This is a worrying development because the power to issue standards is vague and can clearly cause damage to technical protections available to users, or even lead to smaller online service providers such as Telegram or Signal from not offering services in India.

In addition to expanding its own powers for granting licenses, the Union Government has also proposed to dilute the powers of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) under Clause 46 of the Telecom Bill, 2022. Key provisions of the TRAI Act, 1997 under which the government, prior to issuing a license to a service provider, had to ask the regulator, i.e, TRAI, for recommendations have been removed. The creation of a licensing regime for providers of OTT communication services has been a consistent demand of traditional telecom service providers (TSPs). According to TSPs, the lack of equal or same regulations over OTT communication service providers creates an uneven playing field, as OTT services are a “substitute” for the services they provide. Additionally, TSPs also argue that the increasing use of OTT communication service providers by users has led them to suffer from loss of revenue due to loss of market share. However, the ‘same service same rules’ argument used by TSPs is unfounded, as there are inherent structural differences between telecom and OTT communication service providers.

D. Compromised user safety, and increase in Executive surveillance powers

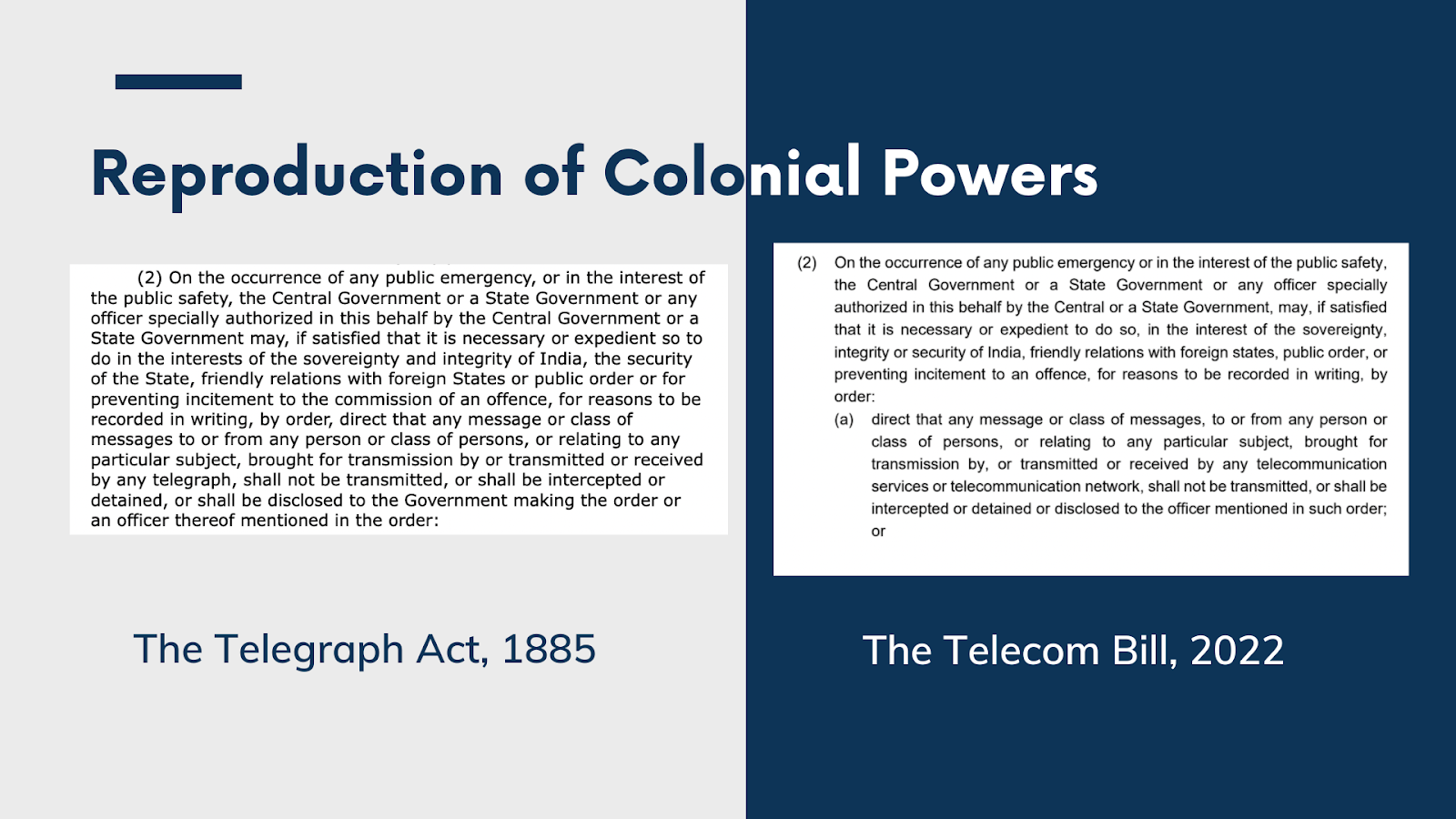

Clause 24(2)(a) of the Telecom Bill, 2022 replicates the requirements of S. 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, 1885 with one major change. S. 5(2) currently authorises the interception of messages transmitted through a telegraph as part of the surveillance framework in the country by the Union or State Government, or any officer authorised on their behalf. Clause 24(2)(a) of the Telecom Bill, 2022 also expands the scope of the surveillance to “telecommunication services or telecommunication network”. As a result, OTT communication service providers such as Whatsapp, Signal etc., which implement End-to-End encryption (E2EE), may now also be required to not transmit, intercept, detain or disclose any message or class of messages to the officer specified in the surveillance request/order. Encryption is also undermined by Clauses 4(7) and 4(8) of the Telecom Bill, 2022, which require licensed entities to “unequivocally identify” all its users, and make such identity available to all recipients of messages sent by such users.

The Government has, sadly, passed up a chance to introduce surveillance reform provisions in the Telecom Bill, 2022. The Telecom Bill, 2022 does not reflect improvements to India’s surveillance architecture on the basis of privacy, transparency, and accountability. Even where the Telecom Bill, 2022 has tried to bring in certain safeguards through the ‘public safety’ and ‘public emergency’ requirements, it must be noted that the power to intercept messages transmitted through a “computer resource” already exists under Section. 69 of the IT Act, 2000, and has been provided to the MeitY. However, Section. 69 does not contain the ‘public safety’ and ‘public emergency’ requirements. Effectively, this means the Government, via MeitY, can bypass the ‘public safety’ and ‘public emergency’ threshold by conducting the surveillance under Section. 69 of the existing IT Act. This makes the procedural safeguards provided under 24(2) practically meaningless.

The decision of the Supreme Court in Justice K. S. Puttaswamy & Anr. vs Union Of India & Ors., as well as the 2018 Justice B.N. Srikrishna Committee of Experts on Privacy Report, expressed the urgent need for surveillance reform. However, the Telecom Bill, 2022 squanders this chance for significant legislative reform based on the knowledge and experience which has been accumulated post independence. Instead, it replicates the colonial moorings of the Telegraph Act, 1885 by transplanting essentially the same provision onto this new Bill and ultimately fails to be the custodian of India’s telecommunications sector in the 21st century.

E. Internet Shutdowns

Clause 24(2)(b) of the Telecom Bill, 2022 for the first time provides a clear internet suspension power, which did not exist as clearly before. However, it fixes none of the issues of the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017. It fails to enact any provisions for judicial oversight over the suspension orders, or to strengthen the powers of the review committee.

The Supreme Court, in Anuradha Bhasin v Union of India, has stated that expressing one’s views or conducting one’s business through the internet are protected activities under Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution respectively. Further, the Standing Committee on Information Technology, in its report on internet shutdowns, has also made a range of recommendations including a review of the legal regime for suspension of internet services, as it found the DoT’s existing process lacks sufficient safeguards. Further, even though the Telecom Bill, 2022 identifies telecommunication as a key driver of socio-economic development, it fails to protect the economic interests of Indian users by not putting in place sufficient safeguards against overbroad suspension of internet services.

F. Offenses and Penalties

Schedule 3 of the Telecom Bill, 2022 lays down clause specific offenses and the penalties they attract. Activities which have been categorized as offenses, and as a result penalized, include providing telecommunication services or establishing a telecommunication network without obtaining a license and use of a unlicensed telecommunication network, infrastructure or network by a person or entity, either knowingly or having reason to believe it to be unlicensed. Clause 48 states that in case of an offense committed by a company, the employees, who at the time of the offense were responsible for the conduct of the business relating to the offense, shall be liable and punished accordingly. Clause 48 read with Clause 47 thus states that, if a service provider such as Telegram or Signal, doesn’t obtain a license from the Union Government, and continues to provide services in India, their officers may be criminally prosecuted. On an even more concerning note, if a user continues to use such services, i.e., services which are being offered by unlicensed entities, they may be fined a hefty amount of 1 lakh INR. The grounds– “having reason to believe so”– may be misused and may put the user at a disadvantage as it appears to place the burden on them to prove lack of knowledge about the license status of any service provider.

Clause 51 states that if the government (Union, State or Union Territory) is satisfied that any information, document, or record in possession or control of any licensee, registered entity, or assignee is necessary to be furnished in relation to any pending or apprehended civil or criminal proceedings, then a specially authorised officer shall on the government’s behalf request such information. Subsequently, the licensee, registered entity, or assignee will have to comply with the direction of such officer. Here, ambiguity in the phrasing of this Clause opens it to misuse. There is an absence of clear parameters on information which may be revealed, and the specific circumstances in which the authorised officer may request it to be furnished to them, as the Clause allows requests to be made even in situations where the officer “apprehends” any illegal activity. This vagueness may lead to overbroad requests for disclosure which could result in the violation of the right to privacy of users.

There is still time for civil society groups, citizens and other interested stakeholders to provide comments on the draft through November 10, 2022. Comments can be sent to naveen.kumar71@gov.in. We hope the next version of the bill will address the concerns raised above; only then can it deliver on the government’s goal to bring Indian telecom policy into the 21st century.

Authors