How To Govern Chinese Apps Without Discrimination Against Asian Diaspora Communities

Matt Nguyen / Nov 22, 2022Matt Nguyen is the Policy Lead for Digital Governance and Rights at the Tony Blair Institute, where he leads work on the future of news, platform governance and digital rights.

This essay is part of a series on Race, Ethnicity, Technology and Elections supported by the Jones Family Foundation. Views expressed here are those of the authors.

Last week, Christopher Wray, Director of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), told lawmakers that the bureau has national security concerns about TikTok, the popular app that is owned by the Chinese firm ByteDance. “Under Chinese law, Chinese companies are required to essentially -- and I’m going to shorthand here -- basically do whatever the Chinese government wants them to do in terms of sharing information or serving as a tool of the Chinese government,” Wray said in the House Homeland Security Committee hearing. “That’s plenty of reason by itself to be extremely concerned.”

Similar fears have been expressed by officials in other democratic governments. Concerns about rising Chinese influence have been increasingly conveyed through the lens of how technology is developed, governed and distributed. As democratic governments enter a new phase of engagement with China that balances national security worries with needed cooperation, understanding how we might govern Chinese apps in a way that squares such concerns with the needs and interests of Asian diaspora communities is paramount. Australia offers a case study in the potential pitfalls, and a possible path forward.

Introduction

The May 2022 Australian election was a moment of vindication for many. Nine years of conservative rule gave way to a coalition of independents seeking climate action, record Indigenous representation and the most diverse Parliament Australia has ever seen. With nearly 1 in 5 Australians having Asian ancestry, this election was a particular turning point for political representation: where the number of elected Asian-Australians makes up half of the total figure ever elected to Parliament from that ethnic group.

This election, however, came at a point of intense alienation for Asian-Australians. The wave of anti-Asian sentiment during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic meant increased discrimination, hate crime and attacks on the community. And rather than being repudiated by the political establishment, when combined with a historic low point in Australia’s geopolitical relationship with China, this wave of hate alongside increasingly hawkish sentiments has translated into our own brand of Down Under McCarthyism.

Like many other countries, Australia has been grappling with the societal impacts of social media for the past few years. At the coalface of this debate are elections, where issues such as misinformation, foreign interference and content moderation become both more apparent and important. How we navigate these issues becomes more complex when the focus turns to non-Western social media platforms - namely those that originate from China. But calls to ban or boycott these platforms would achieve the exact opposite of their intended aims to protect democracy, as huge proportions of the Australian population would be excluded from our political processes.

In our attempts to reign in ‘foreign’ Big Tech, how might we balance our national security anxieties and interests with the new opportunities for engagement these platforms have given us? It is crucial to separate real concerns over security and the integrity of Australian elections and political discourse from the bigotry and discrimination that has long targeted Asian-Australians.

The Asian Diaspora in Australia

Whilst multiculturalism is regularly touted nowadays as a fundamental national value, the exclusion of Asians from Australian society has deep historical roots.

Prior to the ‘establishment’ of modern Australia, the influx of Chinese migrants from the gold rush meant that distrust and violence against non-white communities was prevalent. After Federation, one of the first pieces of legislation passed from the newly formed government was designed to specifically limit non-British immigration representing the formal start of the White Australia Policy. This policy had a profound impact on Australia’s demographics, decreasing the proportion of Asians from 1.25% of the population at Federation to only 0.21% by the end of World War II. Following WWII, successive governments began dismantling this policy until its full abolishment by the government of then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam with the passage of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. From 1978, Australia became the second country in the world (after Canada) to implement a national multiculturalism policy; since then, its value to society has been made manifest.

AncestryProportion (%)TotalChinese5.471,390,639Indian3.08783,953Filipino1.61408,842Vietnamese1.32334,785Nepalese0.54138,463Asian Australians17.4(Source: ABS Census 2021 found here)

These policy reforms paved the way for waves of migration from Asia. From the refugee crisis in Vietnam and Cambodia, skilled migration from India, and people escaping political turmoil in the Philippines and China, Australia became a primary destination for many in the region. Whilst this has led many in the political establishment to label Australia as ‘the most successful multicultural nation on Earth’, various voices still see rising diversity as a threat to the national identity.

As of 2021, nearly half of all Aussies have at least one overseas-born parent. From the first census in 1911 that indicated 18% of the population was born overseas, 111 years later it’s risen to 30% of the population (predominantly from Asian countries). But even with these numbers, the path for migrant communities to realize their place in business, civic and political leadership in Australian society still has a long way to go.

Asian-Australians in Politics and Leadership

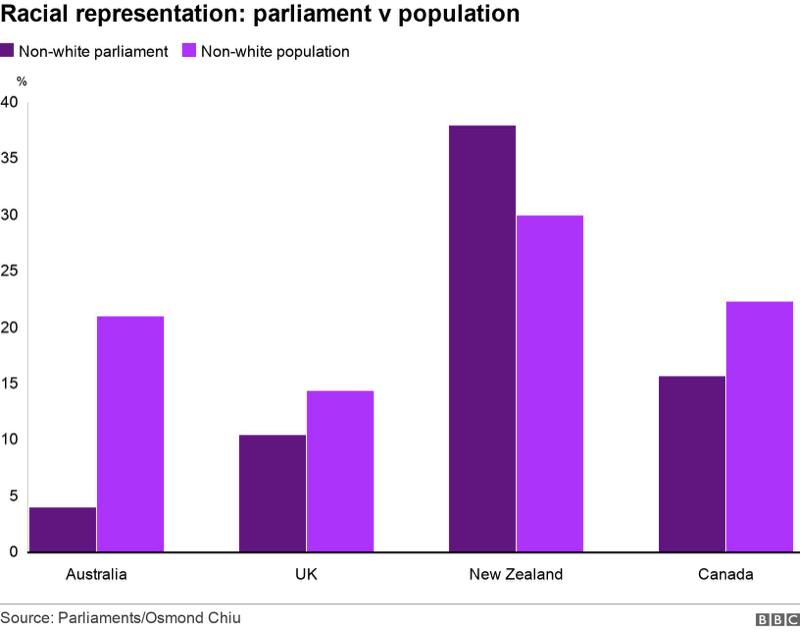

The legacy of exclusion resulted in severe under-representation of Asian-Australians in politics. Prior to the recent election, 96% of Australian lawmakers were white, trailing behind other similar multicultural, liberal democracies such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand.

This lack of representation of Asian-Australians extends far beyond politics into all areas of leadership in Australian society, and is known as the ‘bamboo ceiling’. But whilst the private sector also limits Asian-Australian progression, the issue is particularly pronounced in the public service.

Chinese-Australians in particular are broadly under-represented, but are increasingly so in the more ‘sensitive’ departments such as ONI (intelligence), Defence or DFAT (foreign affairs) as opposed to Education or Treasury. One of the main reasons for this are the lengthy periods associated with obtaining security clearances, on average 6 months longer for Chinese-Australians. Greater scrutiny of China links is not just an Australian phenomenon. In the US between 2010-2019, you were nearly twice as likely to get your security clearance denied if you had any familial or financial links to China - prior to this the denial rate was similar to other countries.

Holding an Election Amidst a Tense Trade War

Three elections ago, relations between China and Australia were much better than they are currently. Amid lofty optimism off the back of a finalized free trade agreement, Chinese Paramount Leader and Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping’s address to a joint sitting of the Australian Parliament and tour of the country would be unthinkable in today’s climate. Instead, years of simmering tension were catalyzed when Australia called for an independent investigation into the origins of COVID-19. An ensuing petty trade war (no lobster and wine!) plummeted relations between the two countries.

Here are the 14 disputes with Australia. https://t.co/tJC6F9LgNs pic.twitter.com/wPDNfhPswN

— Eryk Bagshaw (@ErykBagshaw) November 18, 2020

A leaked dossier of Beijing’s grievances against Australia, released November 2020

The 2022 election saw the Scott Morrison government double down on a hardline national security and anti-China rhetoric, at a point where a wave of anti-Asian hate saw more than 8 in 10 Asian-Australians reporting at least one instance of discrimination. From labeling Richard Marles, the future Minister of Defence, as the Manchurian candidate to billboards from right wing campaigning groups associating Xi Jinping with the Labor Party, this all out offensive was costly, swinging almost all electorates with <10% Chinese ancestry to the Labor party.

While the hawkish positions that at times bordered on racial vilification from the conservatives was clearly miscalculated, their sentiments belie real concerns regarding foreign interference and electoral integrity more broadly. How social media platforms impacts elections, society and democracy has been one of the topical policy conversations over the past few years, and as more non-Western social media platforms gain popularity, there is an even greater need to understand the nuances of platform governance while avoiding the pitfalls of reactionary solutions (i.e. let’s ban it!).

What is WeChat?

At the eye of the storm is a Chinese app called WeChat. Developed by Tencent (one of China’s main technology companies), WeChat is the most popular online platform amongst Chinese migrants, and as of 2020 had around 700,000 daily active users in Australia. Far from just being a social media platform, WeChat also has messaging, calling, mobile payments and ecommerce functions, making it a ‘one stop shop’ for everything online. For Chinese-Australians this app is the public square. WeChat is the dominant source for both Chinese-language (at 86%) and English-language (at 63%) news for this ethnic group.

WeChat has a ‘one app, two systems’ approach, where the international version of WeChat is subjected to less severe censorship and data governance obligations than its Chinese counterpart (called Weixin). The version of the app depends on the device used to register, meaning that many Chinese visitors, students and business travelers remain under the governance framework of Weixin even outside of China’s borders. In September 2021, Tencent updated its terms of service to assure international users of the system’s discretion (and also in response to evolving data storage and localization legislation in China). It gave users a choice to switch registrations over to non-Chinese numbers, however with migration taking as long as 10 days and resulting in decreased functionality, many Australians chose to keep their Weixin accounts. Additionally, WeChat Official Accounts (WOAs), which give accounts functionality akin to a Facebook page and are the preferred choice for politicos, still require registration with a Chinese number.

The Witch Hunt on Chinese Technology

Since mid-2020, from India’s TikTok ban to investigations of Huawei, global scrutiny on Chinese technology firms has been at an all time high. Accusations range from surveillance to censorship to foreign interference, reflecting the decline in relations and trust between China and the rest of the world at large. Some of these accusations are well founded, while others are less so.

Privacy and Surveillance

Concerns over the data practices of Chinese apps, backed up by evidence uncovered by journalists, have become so commonplace that they should be taken as fact. Right after the election, leaked audio from TikTok in the US revealed that user data had been frequently accessed from China. In Australia, a report released around the same time pulls into question where data from the app is actually processed, and the risk this poses for security and privacy. A review into data harvesting of WeChat and other Chinese apps was announced by the Home Affairs Minister shortly after the election.

Censorship

As opposed to Weixin, where a sophisticated system of direct algorithmic censorship ensures CCP control over the online environment, WeChat’s censorship regime is more indirect.

Firstly, it’s well documented that many users of the app self-censor, where users avoid ‘sensitive’ topics around international relations, human rights and COVID-19, and could be a contributing factor to why Chinese-Austrailans rarely share their views online about politics and government - particularly about China.

Further, opaque platform policies (although not dissimilar to other social media platforms) mean that content moderation and censorship decisions are held entirely within the company. From activists to artists, even foreign-registered WeChat accounts have posts and messages actively censored if they touch too closely on sensitive issues.

Finally, many Australian users and politicians who register with a Chinese number to gain access to increased functionality are subjected to the stricter content rules of Weixin. Even then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison had a post removed that criticized a Chinese government official for publishing a doctored image of an Australian soldier holding a knife to an Afghan child (in response to the release of a report alleging war crimes by the Australian military). A note on WeChat said that the post was unable to be viewed as it ‘violated company regulations’.

Misinformation and Foreign Interference

Even though many within the Australian establishment have expressed concern about China’s ability to influence public opinion, proof of whether it has succeeded in impacting public discourse has been limited. Definitively proving the efficacy of state-sponsored disinformation campaigns is extremely challenging, as the network of astroturfing, proxies and shadow organizations used to achieve these goals are intended to be hidden, but incidents overseas reveal the potential risk towards Australian democracy. The 2021 Canadian election saw significant disinformation campaigns against an outspoken Hong Kong-Canadian politician, which contributed to him losing his seat. Kenny Chiu, a Conservative member of the Canadian Parliament and critic of the Chinese regime, faced significant (and falsified) opposition to proposed legislation intended to bring in more transparency requirements.

In reality, the majority of misinformation and disinformation spread on WeChat comes from domestic Australian actors. From statements that Labor will fund school programs to ‘turn students gay’ and ‘refugees flooding in and taking your wealth away’ to misinformation on how to vote, such posts are mostly forwarded between private groups. The confluence of platform design that facilitates these ‘communities of trust’ to form and the segregated nature of these online spaces leaves WeChat very susceptible to information disorder.

Paradoxically, while Chinese disinformation campaigns tend to go after more conservative candidates (due to a higher likelihood of them being China hawks), domestic misinformation tends to target more left-leaning politicians (due to the Chinese diaspora being more likely to engage with socially conservative and economic narratives).

WeChat Use Becomes a Dogwhistle for Patriotism

Early in the election period, Prime Minister Scott Morrison was rocked with a scandal. His WeChat account was sold to a company based in Fuzhou, renamed, losing him the ability to reach 76,000 subscribers. It’s important to note that account transferrals are completely allowed on the app. While foreign politicians are not allowed WOAs, they can still obtain one through registration services that pair foreign accounts with Chinese numbers - a tactic used by many politicians as these types of accounts allow for more desired campaigning features (such as push alerts and being able to broadcast).

As the news broke, many people in the Australian political and media elite quickly jumped into accusation mode. From allegations of hacking to CCP interference, it was galvanizing to both security and political folk alike - time to ditch WeChat. Senator Paterson, a libertarian who chaired the Parliament’s intelligence and security committee, said that the takeover was ‘very likely’ sanctioned by the CCP and amounted to foreign interference, joining the chorus of pundits calling for a ban on WeChat.

Even Gladys Liu, the first Chinese woman to be elected to the Australian House, was quick to renounce WeChat. This is despite the fact that she had expertly used WeChat on two separate occasions to win seats for the Conservative party - once for her predecessor and once for herself. Even as other members of her party continued to push ads on WeChat, Liu’s precautionary actions to publicly display nationalistic loyalty not only hark back to her experiences years before, when her previous links to overseas Chinese organisations were used to insinuate links to the CCP, but also to the persistent ‘otherness’ Asian-Australians face throughout society. It followed another instance where in a Senate inquiry on diaspora experiences, a Conservative Senator demanded three Chinese-Australians to unequivocally condemn the CCP, a question which many condemned as racially targeted. For Liu, struggling to hold onto a marginal seat where a quarter of the population speaks Chinese, the decision to not use WeChat was costly.

The Difficult Task of Platform Governance

The aftermath of the US 2016 election, from which evidence emerged of Russian interference via social media, firmly established ‘reigning in Big Tech’ as a common policy goal in many democracies. A few years on, translating this call into tangible action has revealed hard decisions, seemingly intractable tensions and systemic inertia. What the Australian experience has shown is that when the regulatory conversation shifts to try and align the actions of non-Western (i.e. non-American) digital platforms - an additional pitfall of parsing through minority alienation and political posturing must be considered.

The increasing securitization of ‘Chinese influence’ within the Australian policy discourse since 2017 mirrors our increasing frustration around social media regulation. While there are unique challenges WeChat poses from a security and geopolitical lens, attempting to parse out rational policy concerns from irrational and bigoted fears will enable a more nuanced and holistic approach towards platform governance.

For instance:

- On susceptibility towards foreign interference - Chinese-Australians trust news that is shared on WOAs the least compared to other sources such as Australian news

- On distrusting firm’s intentions - whilst there is evidence that the purported assurances from WeChat around transparency, privacy, accountability and safety are disingenuous, the Facebook Files and other whistleblowers have shown that this hypocrisy also occurs elsewhere

- On censorship - content moderation decisions, whether on Facebook or WeChat, both happen at the discretion of these firms and their ‘Community Guidelines’. Whilst there have been some efforts to add a layer of independent governance to these efforts (most notably Facebook’s Oversight Board), key questions remain - how should these quasi-independent transnational governance initiatives fit into our existing state-centric governance model and will privately-led governance initiatives ever manage to account for public interest? Would a ‘Tencent Oversight Board’ be received with the same level of legitimacy? And how might these initiatives be constructed and integrated in a way that ensures buy-in.

What this illustrates is that while security concerns for WeChat are a consideration, many of the fundamental issues WeChat poses are fundamental platform governance policy problems.

A path forward

As our new MPs make their way to Canberra, the responsibility of regulating social media now falls to them. But what the pandemic made clear is that Chinese platforms are a lifesaving communications channel for the Asian-Australian community. Acquiescing to hawkish calls to ‘boycott’ them is not only overly simplistic, but will serve to further alienate huge sections of the Australian public.

Instead, legislators must work towards doubling down on engagement and creating the rules and systems to ensure that this engagement is safe and trustworthy. And whilst it’s a task that won’t be featured in a sensationalized Murdoch hit piece, it will do more to enhance Australian democracy than any media firestorm will. Here are three key recommendations to achieve these goals:

- Shift investment towards digital-forward diverse media to combat misinformation

As one of the first countries in the world to establish a public broadcaster catering specifically to culturally diverse communities, Australia has a legacy of diverse communication. Today, Australia has a diverse media market, but there remains a clear skew towards traditional forms such as print and radio. Even as online media outfits begin to proliferate, many of these outfits originate from migrant students sympathetic towards China’s positioning on various issues. An unfamiliarity around using WeChat amongst Australian media and business outlets has left this digital public square without a counterbalance.

LanguagePublications/PrintRadioTVOnline Chinese80many1 50Indian5036211Filipino53014Vietnamese161425Cultural media market in Australia. Source: Leba - Australia’s largest advertising agency for culturally and linguistically diverse media.

Facilitating plurality within this environment is a complex and active task, and governments should employ multiple levers to increase diversity and representation, particularly within digitally-native media operations. This should include;

- Incentivising traditional media outlets to establish a presence amongst foreign-language platforms - including bi-lingual publication

- Incentivising the diversification of newsrooms, and ensuring that journalistic standards are upheld

- Active funding of new digital media startups that represent diverse and contextual viewpoints

This is particularly important as second-generation communities, who are more digitally literate and have completely different experiences/identities than their migrant parents, become more visible in Australian society. One of the most prominent Facebook groups that provides a forum for the unique experiences of the Asian diaspora - Subtle Asian Traits - with nearly 2 million members was started by a group of Chinese-Australian high school students in Melbourne. Continuing to invest in increasing the diversity of culturally specific media across a wide range of channels is the best way to combat the unique risks around misinformation and information disorder facing minority communities.

- Establish avenues to compel platform engagement in governance processes to combat distrust of foreign social media companies

A holistic platform governance regime should combine:

- Domestic action that combines a multistakeholder approach with equipping independent regulators with the appropriate powers to ensure proper transparency, oversight and accountability, and

- International engagement so that legislation, processes and structures are built through consensus and alignment with international norms

Domestically, hard levers such as mandating researcher access, requiring company and algorithmic audits from independent bodies, and ‘truth in political advertising’ legislation could be considered. In many of the key platform governance policy debates, the focus has been mainly on Meta and Google - however efforts to understand, engage and cooperate with alternative platforms must included to ensure that our regulatory regime applies to all actors.

Internationally, as key geographies seek to establish their sphere of influence (via the EU’s Digital Services Act, the UK’s Online Safety Bill, or U.S President Joe Biden’s principles for tech accountability), ensuring that consensus is achieved will be a significant challenge - particularly as more and more non-American social media platforms begin accumulating larger and larger user bases. It will require diverse coalitions, novel governance frameworks and new institutions. Working towards this new digital compact will require Western democracies to broaden the tent, engage in good faith and center pragmatism, while balancing liberal values - a task that is only possible through dialogue.

- Continue using alternative platforms to increase the political participation of diverse communities to combat alienation

Ultimately, alternative social media platforms are an unparalleled way for minority communities to obtain information and realize their democratic rights. This isn’t limited to WeChat, but platforms such as Zalo (Vietnam), Line (Japan), KakaoTalk (Korea) and WhatsApp all have unique usage patterns amongst various diasporic communities in Australia, even if their dynamics are less researched. What is clear is that even with the risks, WeChat not only enables greater political participation but facilitates public service, information delivery and civic engagement.

For political parties, candidates and advocacy organizations - taking a considered approach that assesses and mitigates risks without losing a valuable communication channel should be considered. This may include:

- Establishing an internal policy on foreign-owned social media platform usage

- Reporting violations to the Australian Electoral Commission or eSafety Commissioner

- Keeping a transparent public register of WeChat ads and paid posts during an election period

Conclusion

Pauline Hanson’s first speech to Parliament

In her maiden speech to Parliament in 1996, Senator Pauline Hanson warned that Australia was at risk of being ‘swamped by Asians’. Even though these comments were made by a fringe far-right politician, they have become emblematic of how the Asian-Australian identity is viewed as a ‘perpetual foreigner’.

Twenty years later from these vitriolic remarks will bring us to the next Australian election, where lawmakers must not succumb to making the New Red Scare a political tactic. Social media platforms, and their unparalleled ability to connect and engage communities, present an unparalleled opportunity for minority communities to add their part to the Australian story. Driving engagement with the Asian-Australian community via the channels they use whilst tackling the real platform governance issues will ensure that Australia’s democracy is strengthened, and could offer an example to other democracies struggling with similar issues.

Authors