How to Avoid Repeating the Self-Regulatory Fallacy with AI

Linda Griffin / Aug 11, 2023Linda Griffin is Vice President of Public Policy at Mozilla.

As governments and society-at-large grapple with the implications of artificial intelligence (AI), we're living through a time of eerie deja vu when it comes to tech regulation. Major corporations are doing their best to assure the public and lawmakers that they know what's right. If we only leave it to them to decide what's next for AI, they seem to be saying, everything will be ok.

We've been through this before at the birth of both the internet and social media. We know precisely what happens when we allow a few giant companies to determine the future of technical progress. We have a chance to forge a different path, and take steps to ensure this great technical revolution brings maximum possible benefit to us all.

There have been some positive early first steps, but they’ve been matched by many of the tried-and-true efforts at deflection we’ve repeatedly seen from tech giants over the last 30 years. And because we’ve all been through this before, we can see these efforts for precisely what they are: attempts to monopolize markets and control the future of another promising new wave of technology.

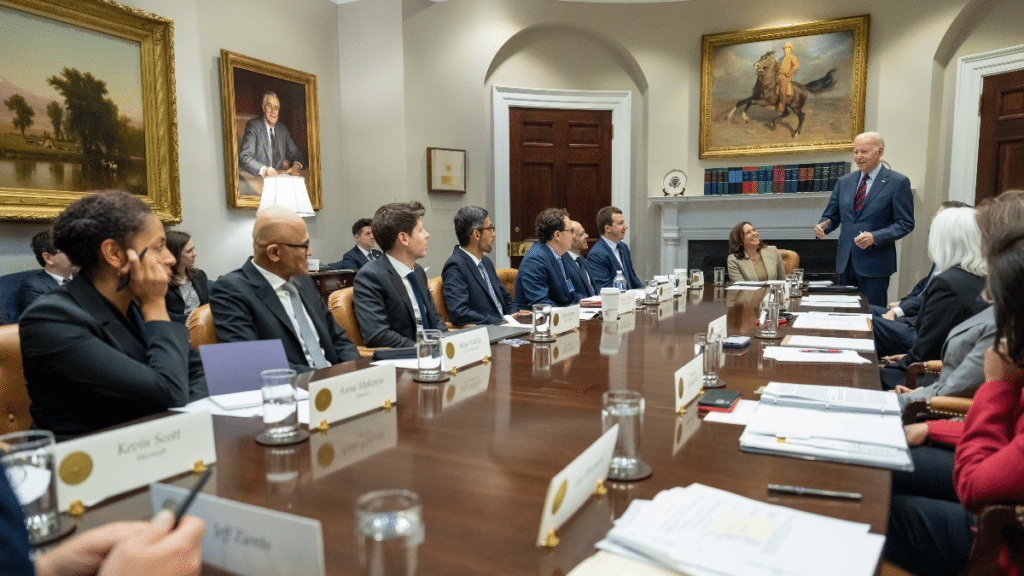

In a nod to the ubiquity of AI and its far-reaching implications, the White House recently released a series of voluntary “Commitments to Ensuring Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI.” The timing is appropriate with new AI developments being announced every day; now is the time for some intelligent and specific government intervention. At almost the same time an enclave of “Big Tech” companies jointly and voluntarily launched the Frontier Model Forum. The aim? To encourage research around the next generation of AI systems, establishing a nucleus of shared information between these companies and governments regarding AI risks.

From the outset, the voluntary nature of these efforts raises serious questions about their credibility. Without enforceable penalties or a regulatory watchdog to hold these companies accountable, the promise of AI safety becomes nothing more than a handshake agreement, and one that is highly likely to be broken when enforced only by tech companies interested in profits, not people. Again, this comes not from a place of speculation, but from one of experience derived from decades of seeing private companies ignore the self-written rules they promised to abide by. History, to paraphrase Mark Twain, is about to start rhyming.

The glaring lack of academic and civil society involvement in shaping the White House Commitments makes these concerns more troubling. The dialogue appears monopolized by large tech companies which, unsurprisingly, are the primary target of the Commitments. Yet there is no dearth of expertise in civil society, academia, and independent research groups, and their absence in this process betrays a failure to engage with all stakeholders meaningfully.

Thirty years ago, lawmakers in Washington, DC showed some remarkable foresight with regard to the possibility of the internet, and working together with a diverse community of invested stakeholders, created legislation that led to one of the most inventive and expansive periods of economic growth the world has ever seen. Since that time, however, the tendency has been too often to default to the opinions and interests of the companies. DC now has a chance to change course, and demonstrate foresight when it comes to AI’s potential to usher in another wave.

The White House's endorsement of internal and external red-teaming is encouraging, but its efficacy diminishes without independent experts validating these exercises. Similarly, references to instruments like the NIST AI Risk Management Framework are commendable but stop short of endorsing international cooperation and data sharing.

The Commitments also skirt the issue of cybersecurity and insider threats, focusing mainly on safeguarding proprietary information without exploring the implications of open-source models. Another commendable yet insufficient provision is the Provenance and Watermarking of AI Generated Content which requires greater engagement of experienced civil society organizations in its development and implementation. Furthermore, the difficulty of the challenge of establishing robust ‘watermarks’ should have been more explicitly addressed – it’s no small feat

The directive to Publicly Report Model or System Capabilities needs clearer language. It could be improved by including mitigation strategies, specified points of contact for addressing concerns, and mechanisms to improve declared system capabilities.

Finally, the emphasis on AI's potential to address societal challenges is laudable. However, it ignores the inherent risks when technical capabilities and computing power are concentrated in private entities primarily guided by what is best for shareholders.

The White House has taken a good, albeit small, first step. But we must not fall into the trap of repeating history – civil society groups, academics, and mission oriented corporations deserve a seat at the table to help shape rules and obligations with teeth. A handshake is not enough, given what’s at stake.

Authors