How the Emerging Market for AI Training Data is Eroding Big Tech’s ‘Fair Use’ Copyright Defense

Bruce Barcott / Mar 4, 2025Bruce Barcott is the editorial director of the Transparency Coalition, a nonprofit group working to create AI safeguards for the greater good. Three of his nonfiction books have been pirated and used to train major AI systems.

Luke Conroy and Anne Fehres & AI4Media / Better Images of AI / Models Built From Fossils / CC-BY 4.0

Around this time last year, news headlines and court documents were full of grand proclamations from AI tech corporations using pirated content to train their artificial intelligence models. Ripping off writers, musicians, and artists in order to build billion-dollar companies amounted to “fair use” of their material, said the fast movers and thing-breakers. Fair use—a concept heretofore applied largely to the quotation of a few lines in a book review—was cited as legal cover for the most brazen and massive theft of intellectual property in history.

OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT, went to London and openly admitted to the UK Parliament that its business model couldn’t succeed without stealing the property of others.

“It would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials,” the company wrote in testimony submitted to the House of Lords. “Limiting training data to public domain books and drawings created more than a century ago might yield an interesting experiment, but would not provide AI systems that meet the needs of today’s citizens.”

Missed in OpenAI’s pleading was the obvious point: Of course AI models need to be trained with high-quality data. Developers simply need to fairly remunerate the owners of those datasets for their use. One could equally argue that “without access to food in supermarkets, millions of people would starve.” Yes. Indeed. But we do need to pay the grocer.

At the same time, other corporations argued that paying the grocer amounted to an economic and logistical hurdle too high to overcome.

Anthropic, developer of the Claude AI model, answered a copyright infringement lawsuit one year ago by arguing that the market for training data simply didn’t exist. It was entirely theoretical—a figment of the imagination. In federal court, Anthropic submitted an expert opinion from economist Steven R. Peterson. “Economic analysis,” wrote Peterson, “shows that the hypothetical competitive market for licenses covering data to train cutting-edge LLMs would be impracticable.”

Obtaining permission from property owners to use their property: So bothersome and expensive.

Anthropic’s point was that without a market for training data, copyright holders could not claim any monetary loss for the real or potential use of their work. And one of the tests for fair use rests on the question of commercial value unfairly taken. From Anthropic’s point of view: No value, no harm. No harm, no foul.

One year later, the emergence of a robust market for AI training data has all but smashed those arguments. It turns out that it is not “impracticable” after all.

This tidal change began quietly in the spring of 2024. Even as its lawyers defended piracy before federal judges, OpenAI began to sign deals with major international media companies for the use of their copyrighted content as training data. Axel Springer, France’s Le Monde, and Spain’s Prisa Media inked agreements to provide the ChatGPT maker with material to train its AI models. In April, the Financial Times signed a deal that required ChatGPT to properly attribute FT summaries to the highbrow business broadsheet.

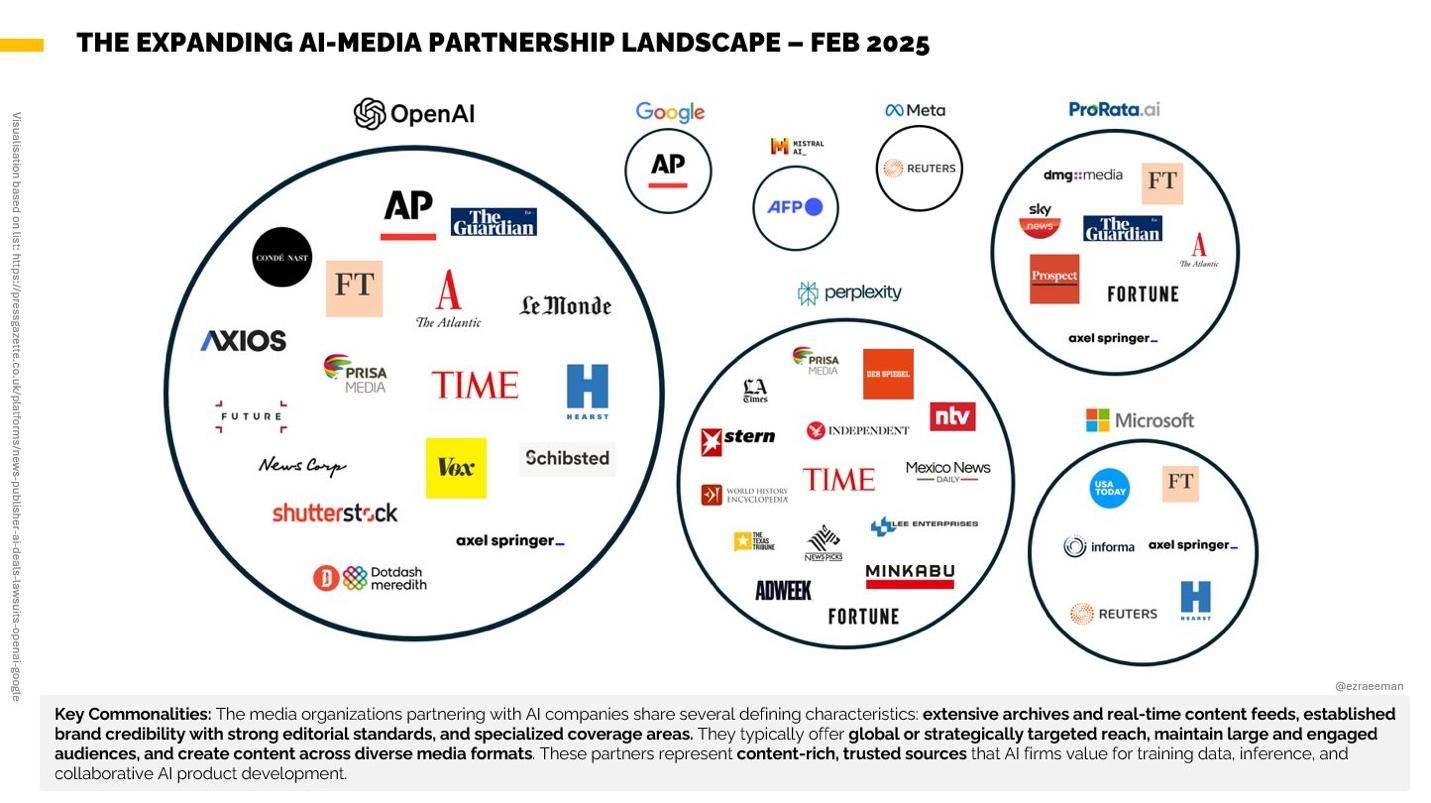

The floodgates opened soon thereafter. Reuters and the Associated Press cut deals with OpenAI, as did Hearst, The Guardian, Conde Nast, Vox, TIME, and The Atlantic. Microsoft did a deal with USA Today. Perplexity gained access to the work of AdWeek, Fortune, Stern, The Independent, and the Los Angeles Times. Not content to merely lease its content, last month OpenAI essentially became part owner of Axios, one of the leading media companies reporting on the artificial intelligence industry.

Today, the AI-media dealmaking landscape is so jammed with familiar names that tally keepers are running out of space. Ezra Eeman, head of strategy and innovation at the Dutch broadcaster NPO, recently published the most up-to-date visualization of the major players and known deals:

The expanding AI-Media partnership: February 2025.

“I feel like I’ve updated this slide more than any other in my decks,” Eeman commented.

However, even as these deals were being announced, there was still something missing: numbers.

Because these were deals between corporate entities, the actual amount of money changing hands remained cloaked in mystery. Clearly, there was a market for high-quality AI training data, but…how much were OpenAI and Meta paying, actually?

It fell to the slow-moving book publishing industry to finally crack things open.

In November 2024, the Authors Guild revealed that HarperCollins, the major publisher owned by NewsCorp, had struck a deal with Microsoft to use some HarperCollins nonfiction titles to train its AI models. The cost: $5,000 per title for the right to use the prose as training data for a period of three years.

Finally! A number!

This is, legally speaking, a really big deal—for reasons I’ll get into below.

First, though, it’s worth noting that the terms of the deal weren’t revealed by HarperCollins or Microsoft but by individual authors whose permission was needed to use their titles. The Authors Guild, which has emerged as a major defender of copyright and authorial rights in this new AI age (and is actively suing OpenAI and Microsoft on behalf of its members), acted as the agent of transparency.

Agent is an intentional word choice. In the world of professional sports it’s widely known that agents leak the terms of freshly inked contracts to reporters at ESPN. It’s a critical element of their work because it sets the market for the next contract, and the next, and the next. If your client is a mid-tier quarterback you can’t know what he’s worth unless you know what Patrick Mahomes is making.

The Authors Guild is aware of this dynamic. It has partnered with a new startup, Created By Humans, which is inventing a new kind of boutique literary agency specializing in AI training rights. Created By Humans is signing up authors in order to offer their works both individually and batched together for training purposes. And now, thanks to the HarperCollins deal, they have an idea of their product’s value in the market.

(Full disclosure: My own nonfiction work has been pirated and illegally used within the internet-scraped Books3 database. I signed up with Created By Humans to legally offer my books for AI training.)

Similar training rights agencies are popping up to legally license the work of artists, photographers, and video creators. Calliope Networks has created a “license to scrape” that gives YouTube creators more control over the use of their content for AI training. Last summer a handful of image licensing firms formed the Dataset Providers Alliance to protect copyright and strengthen the use of legally licensed images in AI training.

To understand why that HarperCollins $5,000-per-title number is such big deal, you need to know about a case known as Spokeo and the threshold for legal standing in federal court.

Basically, if you want to sue a company like OpenAI for causing harm—in this case, stealing the copyrighted property of others—federal courts require you to show actual harm. In a 2016 case known as Spokeo Inc. v. Robins (it involved an inaccurate credit report, but you don’t need to know much more than that), federal courts established a precedent that plaintiffs must show that they “suffered an injury in fact that is concrete, peculiarized, and actual or imminent.”

Because this occurred in capitalist America, that’s been largely interpreted to mean a plaintiff needs to show financial loss or monetary harm. Without it, a lawsuit won’t even be heard in federal court. The plaintiff will be denied standing.

That’s what happened in an early AI copyright lawsuit, Raw Story Media v. OpenAI, in which two alternative media outlets sued OpenAI for infringement. In November 2024, just days before the leaking of the HarperCollins number, a federal judge dismissed the Raw Story lawsuit because the lawyers for the alternative media firms that joined the suit couldn’t show actual monetary harm. Raw Story didn’t have evidence connecting OpenAI’s use of its content to the “actual or imminent” loss of revenue.

Today, just a few months later, we have the evidence that was not available to the Raw Story lawyers. The copyrighted Raw Story content does have actual monetary value, and the use of that content without consent represents theft. Why? Because now we can point to a thriving market for legally licensed AI training data (see Exhibit A above, courtesy of Ezra Eeman) and an actual price paid for the use of that training data.

The confirmed existence of that market will have a profound effect on federal copyright cases moving forward. Already, we’re seeing more decisions coming down in favor of content-owning plaintiffs.

In early January, documents in the Kadrey v. Meta lawsuit, a leading copyright infringement case against Meta and its Llama AI model, revealed that members of Meta’s AI team were clearly aware that they were using (to quote their own words) “pirated material” to train their model. “Using pirated material should be beyond our ethical threshold,” one AI engineer wrote to another.

Meta’s attorneys attempted to squelch any further discovery of the company’s internal communications, but US District Court Judge Vince Chhabria blasted their motion as “preposterous.”

“It is clear that Meta’s sealing request is not designed to protect against the disclosure of sensitive business information that competitors could use to their advantage,” he wrote. “Rather, it is designed to avoid negative publicity.”

A few weeks later, the judge in another federal copyright infringement case came to a similar conclusion about Ross AI, the company accused of stealing intellectual property from Thomson Reuters and its legal research platform Westlaw. “None of Ross’s possible defenses holds water” against accusations of copyright infringement, wrote US District Court Judge Stephanos Bibas.

Look for more of these decisions in the weeks and months ahead. And look for the big AI tech corporations to start scrambling to settle out of court. The lack of an established market for AI training data, with evidence of actual money changing actual hands, was a cornerstone of their defense.

This one-two punch—the HarperCollins $5,000 disclosure and the deals AI developers are cutting with media companies—has crumbled that cornerstone.

Copyrighted material has actual monetary value as AI training data. He who steals it does not steal trash. He steals my purse.

Authors