How Tech Companies Can Make Recent AI Commitments Count

David Morar, Prem Trivedi / Jul 26, 2023David Morar, PhD is Senior Policy Analyst and Prem Trivedi is Policy Director of New America’s Open Technology Institute.

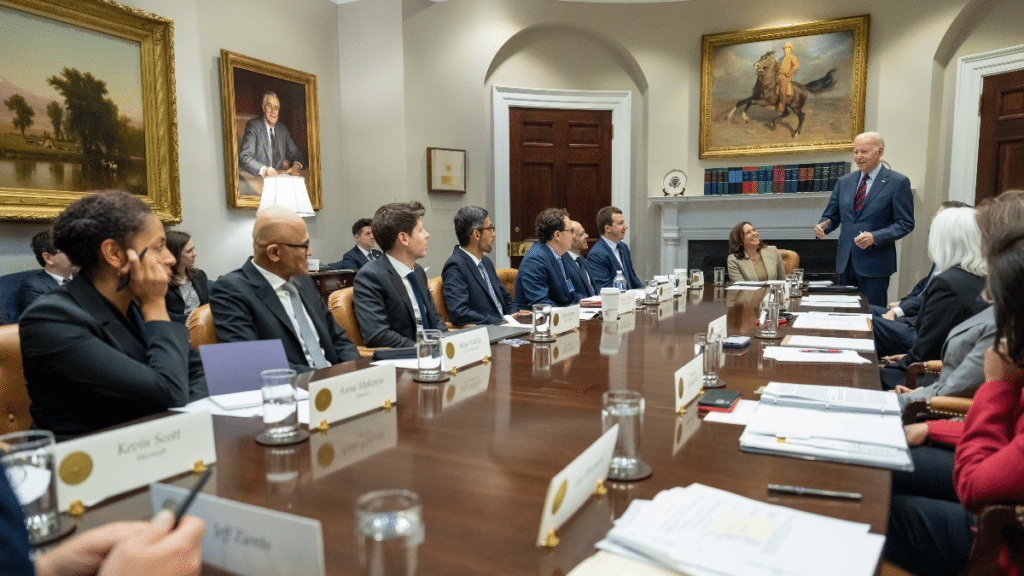

Last week, U.S. President Joe Biden announced alongside CEOs of leading AI companies that the White House had secured “voluntary commitments” from seven companies to build safe and responsible AI systems. This announcement is proof of the Biden administration’s continued focus on managing both the promise and the perils of artificial intelligence. And participating companies deserve some credit for making reasonably detailed statements of intent. The press release and accompanying statement of commitments emphasize that the document is “an important first step” toward the development of laws and rules.

That acknowledgment is important, but it is equally important that such a first step produces meaningful action on its own. On that front, much work remains. Building an effective voluntary commitments process requires incorporating inputs from civil society into the lifecycle of companies’ internal governance process. It also requires identifying specific timelines for the deliverables, along with establishing auditing and monitoring mechanisms.

Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft and OpenAI agreed to eight commitments across three categories of principles — safety, security and trust. The commitments include internal and external security testing, information sharing on AI risks, investments in cybersecurity safeguards around model weights, third-party discovery and reporting of vulnerabilities, robust technical mechanisms to alert users of AI-generated content, public reports, prioritizing research on AI risks like bias and privacy concerns, and a commitment to build systems that address “society’s greatest challenges.”

The commitments are welcome, but vague or incomplete when it comes to accountability, enforcement, and timelines. Addressing these gaps is critical. Voluntary commitments need clearly defined accountability mechanisms to be effective, and civil society partnership and oversight is notably absent in the text. That gap increases the risk that the commitments process will turn into a narrow compliance exercise rather than a comprehensive effort to think through product development processes and risk mitigations that benefit society. For instance, the document notes that the specified commitments will remain in effect until “regulations covering substantially the same issues come into force.” While the statement is understandable, legislative requirements — at least in the United States — may be a long time coming. All the more reason, then, that companies should swiftly define prudential and ethical guardrails that exceed current and expected legal compliance requirements.

But a strictly self-regulatory regime is unlikely to produce that sort of outcome. So what would it take to build a more effective governance structure that goes beyond a compliance mindset and ensures meaningful accountability? These voluntary commitments need an infusion of democratic accountability, oversight, and enforcement mechanisms if they are to avoid devolving into arbitrary corporate decision making.

First, advocates and academics should have integral and visible roles in creating the standards and processes that will give concreteness to public commitments. In that respect, the agreement misses a key opportunity. The statement of voluntary commitments limits civil society’s role to consultations at companies’ discretion while developing safety standards. These discretionary consultations do not even appear under the “Trust” principle, where consultation with diverse civil society organizations is essential. This limited approach could leave civil society in the position of simply reacting to released public reports or demanding faster progress. An ongoing consultation process among companies and civil society would build accountability into the lifecycle of companies’ development, better incorporate equity and fairness into company decision making, and give teeth to the enforcement of internal rules and standards that are developed pursuant to these commitments. A consultative process might lengthen the process of executing on these commitments, but it is also likely to result in more credible baselines that could inform U.S. legislation and regulation.

Second, a voluntary commitments process should articulate target timelines for various outputs, including beta and public releases of watermarks, public reports, and other external communications. Absent such targets, there is little to compel companies to prioritize public transparency while they respond to fiercely competitive product development cycles, grapple with technical challenges, or claim to focus on AI’s existential risks to humanity.

Third, companies should define mechanisms to make their commitments enforceable. Although voluntary agreements lack government enforcement, their legitimacy relies on enforceability through other mechanisms. What’s needed is for companies, with civil society involvement, to establish clear procedures for interim reporting, independent auditing, and comprehensive monitoring. Further, companies and civil society should collectively define and enforce consequences for companies that fail to meet the standards that they themselves establish. Without these accountability and enforcement mechanisms, the commitments announced this month could prove to be little more than a self-governance thought experiment. Toothless self-regulation would arouse the ire of Members of Congress and regulators and might produce ill-conceived legislative and regulatory responses.

Yet to be clear, making these voluntary commitments more concrete and meaningful is no substitute for U.S. legislative and regulatory action. We need both strong legislation and accountable private governance structures. Thoughtful, cross-sector legislation focused on algorithmic accountability and fairness is vital. Comprehensive federal privacy legislation would address many concerns about fair data use, discrimination, and bias in AI models. It would also shift our legal framework from a notice-and-consent model to a data minimization framework that requires companies to limit data collection and tie uses of data to the purposes for which that data was collected. These protections are not just about AI; they are also clearly responsive to many of the core concerns currently debated.

To truly succeed, private governance structures like these require, at a minimum, the addition and active involvement of civil society along with other important structural mechanisms. Without stronger enforcement capabilities, clear timelines, and the goal of going beyond an anodyne compliance-only mindset, these voluntary commitments on AI will fall short of their potential.

Authors